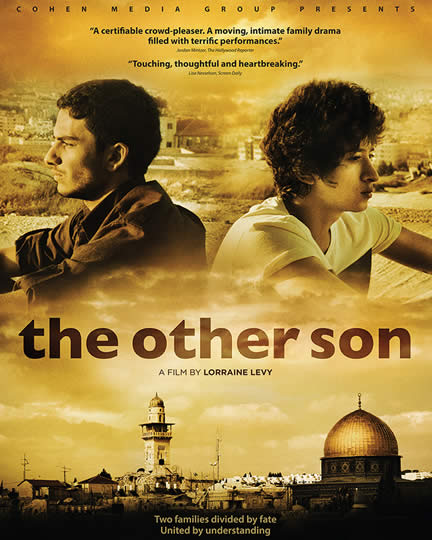

French writer-director Lorraine Levy’s “The Other Son” aptly uses a trope of classical theatre, two babies switched at birth, to dig at the tragic ironies of the Arab-Jewish problem.

French writer-director Lorraine Levy’s “The Other Son” aptly uses a trope of classical theatre, two babies switched at birth, to dig at the tragic ironies of the Arab-Jewish problem.

The familiar plot device appears in Restoration and Elizabethan comedies, Gilbert and Sullivan operas, and even Mark Twain’s “The Tragedy of Pudd’nhead Wilson.” American soaps “The Young and the Restless”, “One Life To Live ” and “Desperate Housewives” have all used the trope. The French title “Le fils de L’autre” (the son of another) is a far better title.

In March of 2011, Ahmed Masoud, a British writer and playwright born in Gaza, told the Guardian that he was switched in the nursery of a hospital in Gaza during a supposed air raid. Recently the story has been outed as false. But as fiction, the conceit works perfectly for Levy’s film. I’m wondering if she read his story?

Two families, living on either side of the Wall separating the Occupied West Bank from Israel, discover their teen-age sons were swapped at birth in a Gaza hospital.

When Israeli teen-ager Joseph (Jules Sitruk “Monsieur Batignole “) takes his blood test in order to enlist in his compulsory Military service, the lab notifies his mother French-born physician Orith Silberg. Shocked Orith must convince her husband Army officer Alon (Pascal Elbe) that she was faithful to him (as the DNA test confirms.) The stunned bourgeois couple can’t face telling Joseph the truth.

The doctors in Haifa explain: During the Gulf War, Joseph and another baby were evacuated from a clinic. In the chaos they were mixed up. The Silbergs brought home the Arab Joseph. Their baby, now named Yacine (Medhi Dehbi-“Looking for Simon”) was given to the Arab couple Said Al Bezaaz (Khalifa Natour “The Band’s Visit “) and Leila (Areen Omari). Meeting for the first time at the office of the Clinic’s director, the two couples grapple with the complications of their long held political-racial ideologies.

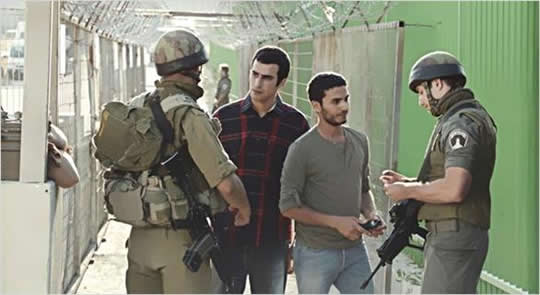

The two loving mothers are the first to negotiate the divide, working to be reunited with their birth sons while doting on the boys they raised. The fathers traverse a thornier path to some sort of extended family. Alon helps the Al Bezaaz family, who suffer both class and racial discrimination, by getting them passes to travel easily to Tel Aviv.

The two boys find the news easier to swallow, though both their lives are forever changed. Devout Yeshiva trained Joseph, learns from his Rabbi (Ezra Dagan) that because his mother is not Jewish he would have to convert. to be accepted in the Synagogue. “Am I still Jewish?’ he worries.

Worldly Yacine (Mehdi Dehbi) who’s returned from Paris with his Bachelor’s degree takes the news calmly, but his violently anti-Zionist brother Bilal (Mahmoud Shalaby), rejects his older “brother” Yacine, as a member of the Occupying elite.

The ironies pile up; sensitive folk singer Joseph has nothing in common with his alpha male father.

Later he discovers his biological father is a musician. In a charming scene, Joseph travels to Palestine and meets his militant blood brother Bilal (Mahmood Shalabi). To break the ice at the uncomfortable family dinner, Joseph sings a song and encourages father Said to join in with his favorite musical instrument.

Levy and co-writers Nathalie Saugeon and Noam Fitoussi nimbly ford the stumbling stones of pure melodrama to deliver a more optimistic story. Beautifully shot by Emmanuel Soyer, the film also benefits from Miguel Markin’s production design and edited by Sylvie Gadmer’s sensitive edit.