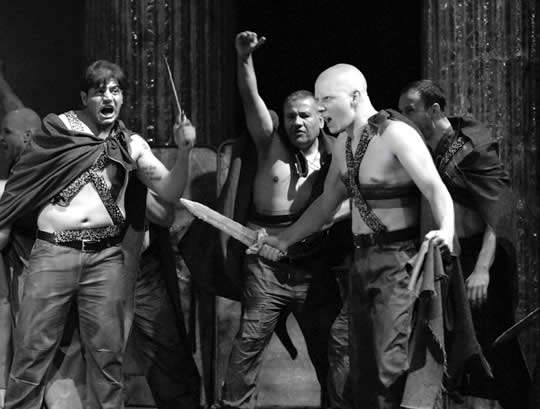

Cesar Must Die, Italia’s 2013 Oscar entry opening scene is in a theater in Rome’s Rebibbia Prison. A performance of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar has just ended amidst much applause. The lights dim on the actors and they become prisoners once again as they are accompanied back to their cells.

Cesar Must Die, Italia’s 2013 Oscar entry opening scene is in a theater in Rome’s Rebibbia Prison. A performance of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar has just ended amidst much applause. The lights dim on the actors and they become prisoners once again as they are accompanied back to their cells.

Then we go to six months earlier, when the warden and a theater director speak to the inmates about a new project, the staging of Julius Caesar in the prison. The first step is casting. The second step is exploration of the text. Shakespeare’s universal language helps the inmates-actors to identify with their characters. The path is long and full of anxiety, hope and play. These are the feelings accompanying the inmates at night in their prison cells after each day of rehearsal.

Who is Giovanni who plays Caesar? Who is Salvatore-Brutus? For which crimes have they been sentenced to prison? The film does not hide this. The wonder and pride for the play do not always free the inmates from the exasperation of being incarcerated. Their angry confrontations put the show in danger. On the anticipated but feared day of opening night, the audience is numerous and diversified: inmates, actors, students, director. Julius Caesar is brought back to life but this time on a stage inside a prison. It’s a success.

The inmates return to their cells. Even “Cassius”, one of the main characters, one of the best. He has been in prison for many years, but tonight his cell feels different, hostile.

He remains still. Then he turns, looks into the camera and tells us: “Since I have known art, this cell has turned into a prison”.

Paolo and Vittorio Taviani brothers, directors of Cesar Must Die, have always worked together on their films as writer directors. They started directing in the early 60s and have made both fiction and documentary films. At the Cannes Film Festival the Taviani Brothers won the Palme d’Or for Padre Padrone in 1977 and the Grand Prix du Jury for La Notte di San Lorenzo (The Night of the Shooting Stars) in 1982. They were awarded the Golden Lion for the Career at the Venice Film Festival in 1986.

Bijan Tehrani: From what I know, just by luck you were invited to a performance by prisoners and it was then and there you decided on making a film about that subject, but what aspect of prisoner’s performance helped you to make that instant decision?

Paolo Taviani: Many people have asked us what problems in prisons inspired us to make this film and it’s clear that Italian prisons have many and awful problems. But on this occasion we didn’t start to think about these kinds of problems. Rather, we took inspiration from a friend of ours who’s a press agent for movies but also for the prison of Rebibbia in Rome.

And this friend of ours told us to please come to Rebibbia because the inmates there were putting up a production of The Tempest by William Shakespeare. We weren’t very excited at first because we were thinking it was going to be classic drama so we put off going there for a long time. But Shakespeare beckoned us and we decided to go.

So we went to see this play and we were immediately touched very strongly by it. One of the inmates at the beginning of the play was reading from one of Dante’s Canto of the Inferno: the one about the famous love story between Paolo and Francesca. Paolo and Francesca were sentenced to live their actual lives in hell and therefore their love was an impossible love. This inmate turned to us and said something with a sweet aggressiveness: “you believe that you understand these verses by Dante and you believe that you understand the pain that he is trying to convey but you don’t; maybe a little… We who are in prison and live apart from our loved women, we can understand what Dante is really trying to say. When we enter prison for the very first time, we leave our women behind. And some of them say they will wait for us. The thought of a woman that is waiting for you to get out of prison is a desperate thought. Other women leave these men, so that is another type of desperation. We cannot touch our women, we cannot smell our women”. He then went on to say, “I told you how I feel and now I am going to read from Dante’s Inferno. But I will not be reading these verses in Italian but in my language which is the Neapolitan dialect.” So he started in his dialect, the same harmony you hear in the film. Both Vittorio and I rediscovered Dante through this new reading in Neapolitan dialect. And the same thing happened when we heard them recite The Tempest in the same dialect.

It had been a long time since we had encountered by chance such a fortunate event. And this kind of emotion is not something we can keep to ourselves because our job is to make films… so we hope we were able to convey these emotions.

Bijan: Why Julius Cesar? Because it’s about Rome or because it is a crime story and the relationships between the characters in Shakespeare’s play resemble those of the mafia?

Bijan: Why Julius Cesar? Because it’s about Rome or because it is a crime story and the relationships between the characters in Shakespeare’s play resemble those of the mafia?

Vittorio Taviani: It is true that the first step was deciding to represent an Italian story and a story about Rome as well. It is also true that the moment when Brutus, who is almost a son to Caesar, assassinates his father and Cesar utters the famous words “you too Brutus, my son?” are part of popular culture in Italy. But it is also true that many elements of the play such as power and conspiracy, internal fights and failed relationships between father and son reflect relationships that are part of the background of the inmates’ lives and culture. So if you remember the play, one of the most memorable moments of the play is when Brutus and Marc Anthony confront each other in front of the body of Julius Cesar. And Marc Anthony says about Brutus four times that he is a man of honor. Now, you have to remember that this is what the criminals call each other in the mafia, “man of honor”. So when inmates started reading Julius Caesar, they said to us, “this Shakespeare, he’s a friend, a brother of ours.” Five hundred years ago, he had already put in words our dramas, our stories. To give an example, let’s take the scene when Julius Caesar is killed. The day we were supposed to shoot this scene, there was a lot of silence and you could feel the tension in the air.

So we start directing the actor, to climb on the step, step back and take the sword. Then we said, “now it’s time to focus, we are about to shoot the murder”. And we said to the inmates, “now you have to concentrate and find within yourself that horrible impulse that draws one man to take the life of another man and see his blood flowing…” and then we stopped. We bit our tongues and thought, “Are we crazy?? We are teaching crime to people who are criminals”. But the inmates wanted to continue: “for us inmates playing this killing means searching in our past, in ourselves, and in a way it means to let go and free ourselves of this incredible weight we bear each day.”

In fact in another sequence we shot a few days later but that didn’t end up in the movie, one of the inmates writes to his wife and writes, “Dear Luisa in a few days I will be part of a play, please come to see me because when I am on stage, I feel like I can forgive myself.”

Bijan: How did you decide on who plays who?

Paolo: We had some auditions as you can see in the film and that sequence of the auditions was very moving for us. It’s a way of holding auditions that we’ve always filmed, even in the past. So we usually ask the actors at our audition to state their name and the city where they live, first dramatically crying and then angrily. In this instance, we were very impressed and taken by the strength of the actors. We weren’t sure when the actors were crying whether they were reciting or whether they were actually crying. It was a strength we had never seen before with other actors. And when we asked them to display their angry side, we understood they were truly angry – they weren’t acting. We told them in the beginning they didn’t have to tell their true name and address, but each one of them did state their true name and address. We asked them why and they said “we know this film will be shown in Italy and we want our friends and enemies to know that we are still here.”

Now, to come to your original question, I would like to point out that the majority of these prisoners had already had some theatrical experience in the prisons, in the theater lab. So we had to select our actors among these people. We assigned the roles to each of them but on one day one of the actors said he didn’t want to play the role he was assigned, Ottavio. When we asked him why, he said inside the prison they had already assigned roles to each other, and that the role we had assigned to him, they had already assigned to a friend of his and he didn’t want to be a traitor. At this point, we said “let’s make one thing clear: in a film there is a boss, the director; in this case there are two directors so there are two bosses; we want to collaborate with you but you must accept our decisions.” So there was a head for the group of actors, the one who plays Cassius who walked to us and said “yes, we understand and respect that but you must understand that we are a peculiar group of actors; I for example have created three orphans in my life.” We were a bit perplexed. It was a tense moment for everyone and we told this group of people we were going home, that we really wanted to make the film but we had to decide how to make it, and to get back to us if they wanted to make this with us.

We went home and were pretty sad because we really loved this project. We had five days of anxious wait and then got a call back from the prison and they told us to come back. So we walked inside this small theater in the prison and were greeted by warm applause. The head of the group of actors said on behalf of all the other ones, “we accept this because you look us straight in the eye and you do do not lower your eyes like some other people do; so you will be our directors and we will follow your directions.”

Bijan: Did you had a screenplay before starting the shoot or did you allow improvisations?

Bijan: Did you had a screenplay before starting the shoot or did you allow improvisations?

Vittorio: In this film everything is true and everything is false. We proposed this text and we proposed roles to the inmates and told them to translate it into their dialects. Other inmates who were not in the play but spoke the same dialects did a kind of quality check to make sure the translation was true to the dialect and the meaning. So it was a very intense collective. During the process, we spent a lot of time with the inmates and they told us a lot of stories. Some of them really impressed us and we decided to weave them in the film along with Shakespeare’s play. The inmates agreed, so we picked two or three and put them in the script. Then, we showed them what we had written and invited their comments or alterations until we had a rock solid script. Every moment that goes in the film was scripted. The moment of documentary of the film was before shooting. We gave the actors some freedom to improvise but without altering these structures of the script, in the tone in which things were said for example… So everything is true and everything is false.

Bijan: Does Cesar Must Die represent what has been happening in Italy’s political scene in recent years?

Paolo: No, not directly. Some people in the audience saw a relationship between our Caesar and the little Caesar we had on our political scene in Italy at the time but I think whoever saw this relationship just had enough of what was going on in Italy. So it wasn’t intentional even though some people saw that.

Bijan: Have inmates seen Cesar Must Die after completion and what was their reaction to it?

Vittorio: A few months after the film was completed, the inmates saw the film and as is usually the case among actors, each actor was focused on their own performance. They really liked it especially seeing it in Black and White because Black and White transforms them into true characters. In the end, we laughed together, we also cried together, because after we were done shooting the film, they were going back to prison and we were going back towards the light. And we all thought of what they told us on the last day of shooting. The actor who plays Cassius, who was sort of the head of the inmates, called us, raised a hand and told us “from tomorrow, nothing here will ever be as it was before.”

Bijan: Do you think an Oscar nomination or winning the Best Foreign Language award could help the film’s exposure?

Paolo: Sure! How could it not? Of course, an Oscar nomination or an Oscar win would help the film’s exposure on the international scene. The film has already been sold in 73 countries. With an Oscar win, we could double this nice number. On a more serious note, it is a very important and prestigious prize, and I must say from looking at past awards, while it must be difficult to select a foreign film winner because there are so many good films from so many different countries, it has been awarded to good films. From what we can see this year being in L.A., there are many very good films this year, fortunately, and unfortunately.