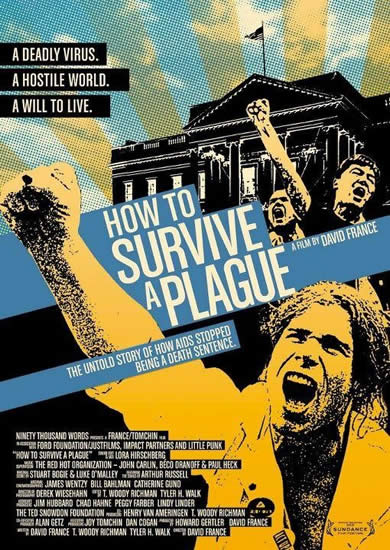

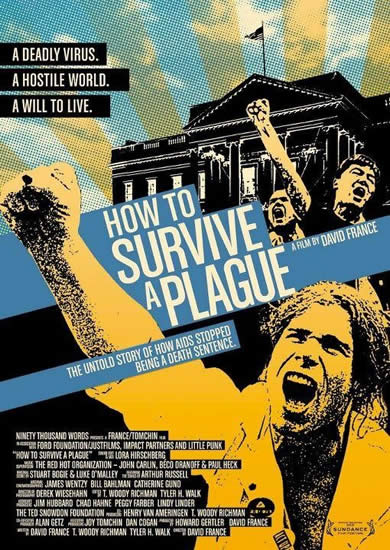

HOW TO SURVIVE A PLAGUE, nominated for the Best Documentary Feature Oscar is a film by first-time director and award-winning journalist David France. (Who has been covering the AIDS crisis for 30 years, first for the gay press and then for the New York Times and Newsweek, among others) David culls from a huge amount of archival footage—most of it shot by the protestors themselves (31 videographers are credited)—to create not just an historical document, but an intimate and visceral recreation of the period through the very personal stories of some of ACT UP’s leading participants. A handbook for all activists who want to make change,

HOW TO SURVIVE A PLAGUE, nominated for the Best Documentary Feature Oscar is a film by first-time director and award-winning journalist David France. (Who has been covering the AIDS crisis for 30 years, first for the gay press and then for the New York Times and Newsweek, among others) David culls from a huge amount of archival footage—most of it shot by the protestors themselves (31 videographers are credited)—to create not just an historical document, but an intimate and visceral recreation of the period through the very personal stories of some of ACT UP’s leading participants. A handbook for all activists who want to make change,

HOW TO SURVIVE A PLAGUE captures both the joy and terror of those days, and the epic day-by-day battles that finally made AIDS survival possible.

Bijan Tehrani: What motivated you to make HOW TO SURVIVE A PLAGUE?

David France: I wanted take the opportunity to go with the benefit of hindsight and look at those dark years of that plague in this country and see really what the legacy of those years was; what was left behind by the period. I knew that a lot of the films and plays and literature about AIDS focused on how awful it was—indeed is one of the most dark chapters in modern American history and in modern world history—but having been a witness to it, I knew that there was more than that and there was a lot of individual empowerment. There was the dawn of AIDS empowerment movement and the dawn of AIDS activism and much of society was really transformed by the work that these people did. I knew that if it weren’t for AIDS activist, we would not be where we are today and we would not have quickly found the drugs that have made it possible to survive AIDS and give people a new lease on life—now 8 million people. I think it is surprising to most people that it was not just the system finding a solution to the problem, but that it took an epic struggle of historic proportions to bring us there. I wanted to enrich the understanding of AIDS and to be more thorough in the telling of the story of individual AIDS patients and the revolutionary impact that AIDS patients and their advocates brought.

BT: How did you go about finding the material for your film?

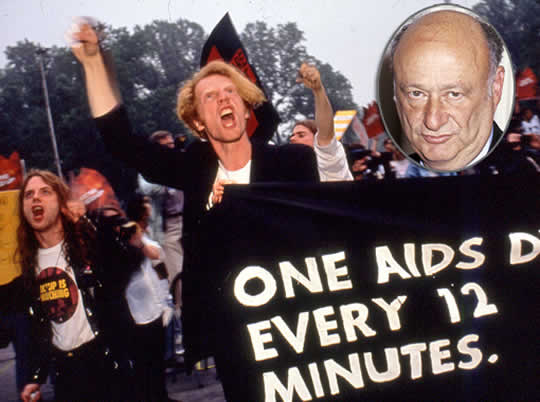

DF: You see that most of the film is built around archival footage. I went back to that footage to see and remember what AIDS looked like; to remember what that plague looked like to New York and the rest of the world, and I was taken by how immediate and how intimate this body of archival footage was. Then it suddenly occurred to me that you could tell the entire story by editing clips together from an enormous archive of footage gathered by activist, artists, and cinematographers of the era themselves, and that it would bring a new generation of people behind the curtain of AIDS to see both the challenges and complexities that the individuals took on, and see and feel the triumph of AIDS activism as it was unfolding. That’s why I chose the approach that I did: By borrowing this footage from so many different sources, that allowed me to tell and intimate and visceral tale about how these drugs came about and how it became possible to survive AIDS.

BT: How did you go about deciding the visual style of HOW TO SURVIVE A PLAGUE?

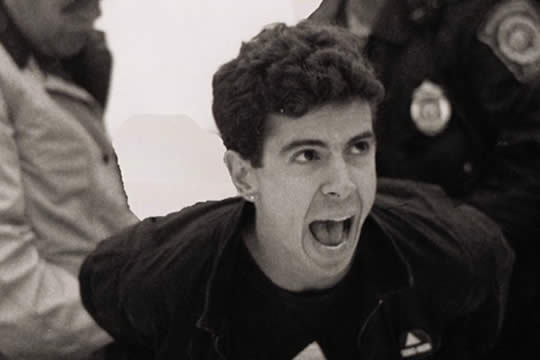

DF: The visual style was something that we discovered in the process. A lot of the footage is old video and it has a certain aesthetic. Some might try to find a way around, but we decided in the editing room that we were going to see the beauty of that and work with it in kind-of a storytelling character. One of the characters in the film is the camera. These are not official cameras—

these are not cameras that document areas, this is footage that people on the ground witnessed with their cameras, so that’s the style. The style is sometimes shaky, but it brings you back to the aesthetic of the 80’s because we embraced it.

BT: You’re bringing something new to the table for many people. How do you hope to effect current audiences?

DF: My goal when making the film was to allow a new version of people to experience the uncertainty of that time. Someone said to me where is all of that footage from ’87 and it moves from ‘88 to ’90, and you wonder which of these activists is going to survive? Who is going to hold their health together through luck and fortune to be able to get to the place that, when the drugs do arrive, they will be able to benefit them? It’s paralleling Hollywood filmmaking where you have those medical thrillers and you just don’t know, and you begin to invest in the individuals the same way we did when it was happening. You feel for them and express this profound hope that they live with everybody else, so I hope that is what comes across when you watch the film.

BT: How did you work with your crew?

BT: How did you work with your crew?

DF: Well, the cinematographers who captured the footage were people who knew that what they were witnessing was a really important part of American history and that no one else was paying attention—no one was seeing what they were seeing, and they wanted to capture that. In that sense, they became the first activist movement to do that sort of self-historicizing; to capture their own history when no one else would, and we see it now in other areas like occupy wall street and all the way forward to this period—they brought the innovation of people shooting their own stories. I worked with a number of them, and one of the people who did the actual shooting was a man named Mike Grier, and I was able to collaborate with him and others who shot footage. The fact that they allowed me to work with their footage was a great and profound honor. The music was largely built on the work of an Avant Garde composer named Arthur Russell, who was a peer of Phillip Glass who had died at a young age. He went back to his estate and asked if it would it be possible to work with what he left behind in order to build the soundtrack and score from there, and they gave us that permission. In a way, it was collaboration from all of those angles to create this project. I really enjoyed working with people from that era to bring this film together.

BT: What is your next project?

DF: I am currently working on a book, which is where I typically toil, and the book is a history of the same period of time.

BT: Best of luck to you, and thank you for speaking with CWB!