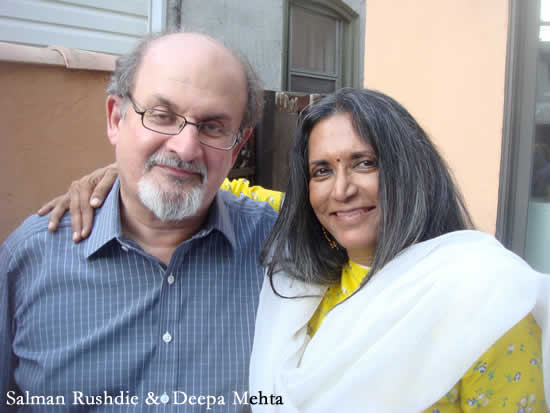

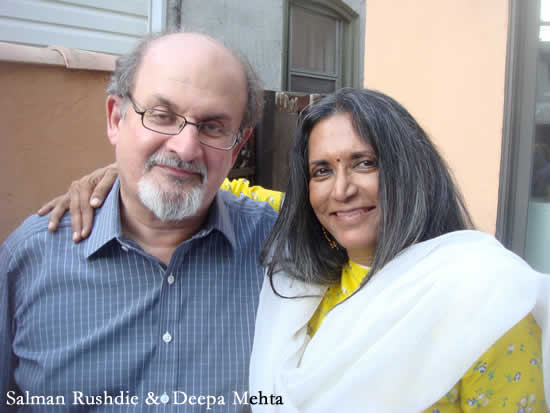

Midnight’s Children is an epic film from Oscar-nominated director Deepa Mehta, based on the Booker Prize-winning novel by Salman Rushdie.

Midnight’s Children is an epic film from Oscar-nominated director Deepa Mehta, based on the Booker Prize-winning novel by Salman Rushdie.

At the stroke of midnight on August 15, 1947, as India declares independence from Great Britain, two newborn babies are switched by a nurse in a Bombay hospital. Saleem Sinai, the illegitimate son of a poor woman, and Shiva, the offspring of a wealthy couple, are fated to live the destiny meant for each other. Their lives become mysteriously intertwined and are inextricably linked to India’s whirlwind journey of triumphs and disasters.

From the unlikely romance of Saleem’s grandparents to the birth of his own son, Midnight’s Children is a journey at once sweeping in scope and yet intimate in tone. Hopeful, comic and magical – the film conjures images and characters as rich and unforgettable as India herself.

Bijan Tehrani: What motivated you to make a film based on Midnight’s Children?

Deepa Mehta: When I told Salman Rushdie that I would like to make a film on Midnight’s Children, it was a very spontaneous request, very instinctive, and to this day if you ask me, I wouldn’t know what to say, as in that moment I didn’t know, but in retrospect, I think it’s a book I have always loved and the reason I love it is its main theme is the search for identity, the search for a home of the young man, Saleem Sinai. We know what it’s like to be in exile – at least I do, as an immigrant, and you have to reinvent your life. That is something that really spoke to me I suppose.

BT: I think this is such a relevant piece for any time period but I want to know how relevant it is to Indian society today.

DM: It’s extremely relevant. We live in a society now where there’s such a huge migrant force, where the people are fighting wars in provinces, and in India there’s a whole insurgency of locals who come from the North to Mumbai to work and are thrown out… There’s a whole migration happening, and I think it’s extremely relevant because people leave their homes behind, their families behind, they go to another place and they have to find themselves again. What about the role of politics in our lives? How can you deny that, whether you live in the United States or India, Canada, or Berlusconi’s Italy? Politics to a large degree define who we are.

BT: It’s a very difficult to make a film from because the narrative belongs more to literature. How did you go about adapting for the screen?

DM: Well, obviously a film is not a facsimile of a book. It cannot have everything that’s in the book, otherwise it would be ten hours long; so you know from the onset that it won’t be possible, whether it’s The English Patient, War and Peace, Atonement… In a way, I really like that because you can then focus on what you think is the essence of the book. So what Mr. Rushdie and I did was we went in separate directions for two weeks and wrote on pieces of paper what we thought individually, without the other person knowing, what the narrative flow or the storyline of the film should be. Then we got back together two weeks later and exchanged the pieces of paper, and both of us were surprised and shocked – and I guess, relieved that what we had written on was almost identical as far as what should be eliminated, what should be the focus, which characters we could sacrifice… Then it became relatively easy because we were both on the same track.

BT: How did you go about casting? Everyone is so perfect for their part.

BT: How did you go about casting? Everyone is so perfect for their part.

DM: That’s a lovely thing for you to say. For me, one of the most enjoyable and challenging parts of making a film is casting and working with actors. I really love that. I love casting, I love rehearsing, and I love working with the actors. And I had an idea, even in the script stage, who I thought would play Mary for example, the nanny who shifted the babies. She’s an actress that I’ve really worked with and I think is superb, Seema Biswas. So there were actors I thought of for certain parts, the grandmother as well, and then we had Indian actors from the States, from England, Sri Lanka and India itself. Some of them had never acted before. I have auditions but I never have them read lines; I spend time with them, and I need to get an idea that they get the character… It’s about character. If the actor understands the character that they’re being asked to play or have an interesting take on it, I think that’s half the battle. I really enjoy that.

BT: The visual style of the film is very beautiful and it also lends itself to the story structure. How did you come up with the visual style for your film?

DM: What I do once I’m done with the script is put it away and I put on my director’s hat. So when I got the final script from Salman, I just put it away for two months then put on my director’s hat and looked at it. That’s the time when I start thinking of color balance. What is the color palette of this film and what is the emotional center of this film? I guess maybe it’s the Indian in me: emotions in India have different colors. Anger is a different color, passion is a different color. Once we had the color palette – and  here we have a really deep royal blue, we have red and green, these are our primary colors- once we have that, we have the primary design of the production design itself. If you get an opportunity to see this film again, you will see that these are the three colors. Then the design of the lighting, of the cinematography, is also – when are we going to saturate the colors? When are we going to take out the colors? How are we going to light it? It all starts from the color palette. What is the wardrobe going to be? It’s all those things.

here we have a really deep royal blue, we have red and green, these are our primary colors- once we have that, we have the primary design of the production design itself. If you get an opportunity to see this film again, you will see that these are the three colors. Then the design of the lighting, of the cinematography, is also – when are we going to saturate the colors? When are we going to take out the colors? How are we going to light it? It all starts from the color palette. What is the wardrobe going to be? It’s all those things.

BT: What is the next project you are working on?

DM: There’s a part of me that just wants to sleep now for six months. I’m so tired! but there’s a couple of things. There’s a wonderful script on the last few years of André Matisse, the painter, when he was a teacher, and he made a chapel in the South of France. He was inspired by a twenty-two-year-old nun who became his muse. It’s a wonderful relationship of the politics of aging I think, and love. I find it very fascinating. So that’s a possibility.

BT: Thank you and good luck with your beautiful film!

DM: Thank you so much. I’m glad you liked it.