Jordan, 1967. The world is alive with change: brimming with reawakened energy, new styles, music and an infectious sense of hope. In Jordan, a different kind of change is underway as tens of thousands of refugees pour across the border from Palestine. Having been separated from his father in the chaos of war, Tarek, 11, and his mother Ghaydaa, are amongst this latest wave of refugees. Placed in “temporary” refugee camps made up of tents and prefab houses until they would be able to return, they wait, like the generation before them who arrived in 1948. With difficulties adjusting to life in Harir camp and a longing to be reunited with his father, Tarek searches a way out, and discovers a new hope emerging with the times. Eventually his free spirit and curious nature lead him to a group of people on a journey that will change their lives.

Jordan, 1967. The world is alive with change: brimming with reawakened energy, new styles, music and an infectious sense of hope. In Jordan, a different kind of change is underway as tens of thousands of refugees pour across the border from Palestine. Having been separated from his father in the chaos of war, Tarek, 11, and his mother Ghaydaa, are amongst this latest wave of refugees. Placed in “temporary” refugee camps made up of tents and prefab houses until they would be able to return, they wait, like the generation before them who arrived in 1948. With difficulties adjusting to life in Harir camp and a longing to be reunited with his father, Tarek searches a way out, and discovers a new hope emerging with the times. Eventually his free spirit and curious nature lead him to a group of people on a journey that will change their lives.

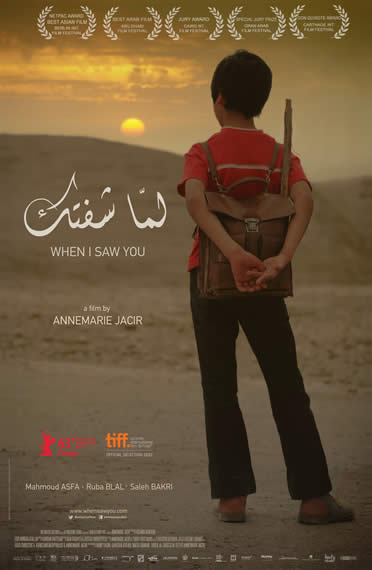

When I Saw You is the story of people affected by the times around them, in search of something more in their lives. A journey full of adventure, love, humor, and the desire to be free, but most of all this is a story about that moment in a person’s life when he wakes up and finds the whole world is open and everything is possible – that moment you feel most alive. It is a journey of the human spirit that knows no borders.

Annemarie Jacir, director of When I Saw You, is an independent filmmaker and screenwriter living in Jordan. Named one of Filmmaker magazine’s 25 New Faces of Independent Cinema, two of her films have premiered as Official Selections at the Cannes Film Festival, one as an Academy Award qualifier, and one in Venice. Her first feature film, Salt of this Sea, was Palestine’s Official Oscar Entry for Best Foreign Language Film and was also noted as the first feature film directed by a Palestinian woman. Salt of this Sea won the prestigious FIPRESCI Critic’s Prize, as well as Best Film in Milan, Best Film in Traverse City and the Special Jury Prizes at both the Osians Asian & Arab Film Festival and Oran Festival of Arab Cinema. The film has won numerous other awards including Best Screenplay (Dubai), the Randa Chahal Prize (Carthage International Film Festival), Cinema in Motion Awards (San Sebastian), Sopadin Grand Prize Best Screenplay nomination and Audience Awards at Houston Palestine Film Festival, Chicago Palestine Film Festival, and Cairo Refugee Festival. The film was released theatrically in cinemas in Europe, Asia, and the USA.

Jacir lived in Saudi Arabia until the age of sixteen, moving between Bethlehem and Riyadh. She then received her formal education in the United States. She began working in the theater; first in set design and then writing and directing plays. Her career in cinema began as an assistant on various sets, and learning to edit. She first worked in the film industry in Los Angeles and then as an editor and camerawoman before attending Columbia University in New York to obtain a MFA degree in Film. After years of shuttling back and forth between projects, Annemarie eventually returned to the Arab world moving to Palestine.

Jacir co-founded Philistine Films, an independent production company, focusing on productions related to the Arab world and has been involved in numerous productions. Jacir also shot and produced the documentary Until When, an in-depth portrait of the lives of several families living in the Deheisha refugee camp as well as several other films. She collaborated with Algerian-French filmmaker Nassim Amouache on A Few Crumbs for the Birds, a documentary sketch of the lives of a handful of men and women eking out a living in the Jordanian town of Ruwayshed (Official Selection Venice International Film Festival, Best film Montpellier, Press prize Clermont Ferrand).

Her short film, Like Twenty Impossibles (2003), the first Palestinian short film to be selected in Competition as an official selection of the Cannes International Film Festival (Cinefondation), went on to be a Student Academy Awards Finalist, and has won more than 15 awards at International festivals including Best Film at the Palm Springs Short Film Festival, Chicago International Film Festival, Institute Du Monde Arabe Biennale, Mannheim-Heidelberg Film Festival, and IFP/New York. Like Twenty Impossibles, named one of the ten best films of 2003 by Gavin Smith of Film Comment Magazine, is a fiction film which wryly questions artistic responsibility as a Palestinian film crew navigates various obstacles of military occupation.

She is co-founder and chief curator of the groundbreaking Dreams of a Nation cinema project dedicated to the promotion of Palestinian cinema. In 2003, she organized and curated the largest traveling film festival in Palestine, which included the screening of archival Palestinian films from Revolution Cinema, screening for the first time on Palestinian soil. She has taught at Columbia University, Bethlehem University, and Birzeit University and in refugee camps in Palestine, Lebanon and currently in Jordan. Jacir is a board member of Alwan for the Arts, a cultural organization devoted to North African and Middle Eastern art. She has served as a jury member to the Copenhagen International Documentary Film Festival (Cph:dox) , the Alexandria Film Festival, the Damascus International Film Festival, Abu Dhabi Film Festival, Dubai International Film Festival, Osians Festival, as well as Cinecolor Award, Argentina. She is a founding member of the Palestinian Filmmakers’ Collective, based in Palestine.

Annemarie teaches screenwriting and works as an editor as well as film curator, actively promoting independent cinema. In 2011, renowned Chinese director Zhang Yimou selected her to be his first protégée as part of the Rolex Arts Initiative. “When I Saw You” is her second feature film. She lives in Amman.

Bijan Tehrani: How did you come up with the idea of making When I Saw You? Did you have a particular motivation?

Annmarie Jacis: First of all, I was very interested in this time period, 1967. I did not live it but I grew up all my life hearing about it. My parents were from Bethlehem in the West Bank and that was the year that my family became refugees. Everything in their language was marked as either before or after 1967. But the 60s were also a time period that was full of hope and change: this was happening all over the world, in Palestine, in civil rights movements in anti-colonial movements… everywhere, regular everyday people were feeling hopeful that their lives could change for the better. And I’d never seen any Arab films dealing with this period.

It is interesting: it is a negative year because it’s the year the West Bank and Gaza were lost but it was also full of hope. I wanted to see how this kind of hope was relevant today because, at least while writing the script, I was not seeing this hope in my generation. Also, I currently live in Jordan and I can see Palestine from across the border but I cannot reach it. I feel a little bit like Tarek, the little boy in the film.

BT: This is a film that even though it deals with difficult times, still has a message of hope. How did you decide to make this film with this message of hope?

AJ: I think we need hope. When you lose everything, it’s all you have. This is a story of a mother and son. The son carries the hope the mother is not finding. She is protective, she is afraid to lose him and of so many things but he keeps the hope alive. You find life in that. People in desperate situations need hope and humor and I think these are important in cinema so I also wanted to have humor in the film. The boy hates the refugee camp, the public bathrooms or standing in line for food, but I wanted to show it not in a victimized way, more of a child’s way of seeing it.

BT: What has been the reaction to your film so far, from Palestine as well as from the Western world?

AJ: It’s been very good. We had the world premiere at the Toronto Film Festival and the audience was very receptive and very generous. In the Middle East, we screened in the Abu Dhabi Film Festival, where it won the Best Arab Film Award, in the Cairo Film Festival where it got a Special Jury Mention and the Carthage film festival where it also won an award. The film takes place in the 60s but there is so much change happening now in the Arab world that I think audiences find the film relevant to what is going on today. The hope is rekindling.

BT: As you are also a poet, there is a poetry of images that shows in the film. How much did your experience in poetry influence your way of filmmaking?

AJ: Thank you. I also love music but cannot make it but poetry, I think, is one of the best art forms. What I like about poetry is the simplicity: you try to express a lot in a simple way. I hope it is something I can try do to in cinema, this is something I want to learn to do better in my craft.

BT: You couldn’t imagine anyone cast any more perfectly than the actors you have in the film. How did you go about the casting?

AJ: The main focus in the casting was Tarek, which was very tricky. The actor who plays him is actually a Palestinian boy who lives in a refugee camp in the North of Jordan. I saw about 200 boys of that age to play him! Tarek is a character who’s a little different from other kids, he’s very open to the world and very smart. It is a little bit difficult to focus at that age or they feel self-conscious. It took a long time but the immediate thing about him was his eyes, which are so expressive, so sad and so happy, and he’s also a smart kid, very quick so he was easy to work with, his family was also supportive. The mother is played by a Palestinian actress I had already seen on screen and I wanted to work with her. Luckily, the boy and her matched very well. The character who plays Layth had worked with me on my first feature film. The rest of the actors are mostly like Tarek first-time actors. Interestingly, as I cast them without knowing it, some of them are the children of those Palestinian fighters. They knew the story and that it was why they came to the audition but I didn’t know when casting them.

BT: In the summer of 2006, you played yourself in a Palestinian film. How much did that experience help you in working with the actors?

AJ: I like to be very open and find the personal in a film. Also, while it is challenging, there is something very wonderful in working with new actors. I didn’t give any of the actors the script but rather set up the atmosphere, the time period, their back story so that they would remain open to how they would naturally react in the situation. I didn’t impose the script on them.

BT: How do you think this film will affect the opinion of people who only know of the issues of Palestine through main media?

AJ: I hope it will be seen for what it is: it’s a simple story but it’s a human story. When we screened the film in Toronto, it was received favorably both by those who knew of the situation in Palestine and those who didn’t. Those who are more aware might know what happened after 1967 and how things evolved but the story int eh film can be sufficient in itself for those who are not familiar with that part of history.