KIDS FOR CASH is a riveting look behind the notorious scandal that rocked the nation. Beginning in the wake of the shootings at Columbine, a small town in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania elected a charismatic judge who was hell-bent on keeping kids in line. Under his reign, over 3,000 children were ripped from their families and imprisoned for years for crimes as petty as creating a fake MySpace page. When one parent dared to question this harsh brand of justice, it was revealed that the judge had received millions of dollars in payments from the privately-owned juvenile detention centers where the kids—most of them only in their early teens—were incarcerated.

KIDS FOR CASH is a riveting look behind the notorious scandal that rocked the nation. Beginning in the wake of the shootings at Columbine, a small town in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania elected a charismatic judge who was hell-bent on keeping kids in line. Under his reign, over 3,000 children were ripped from their families and imprisoned for years for crimes as petty as creating a fake MySpace page. When one parent dared to question this harsh brand of justice, it was revealed that the judge had received millions of dollars in payments from the privately-owned juvenile detention centers where the kids—most of them only in their early teens—were incarcerated.

Exposing the hidden scandal behind the headlines, KIDS FOR CASH unfolds like a real-life thriller. Charting the previously untold stories of the masterminds at the center of the scandal, the film reveals a shocking American secret told from the perspectives of the villains, the victims and the unsung heroes who helped uncover the scandal. In a major dramatic coup, the film features extensive, exclusive access to the judges behind the scheme.

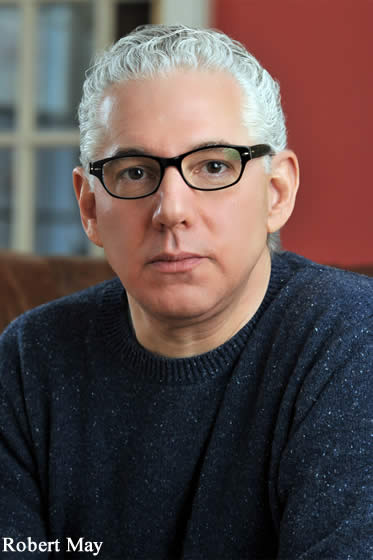

Here is an interview with Robert May director of KIDS FOR CASH. Robert May’s past projects have included: THE WAR TAPES, winner of Best Documentary at the 2006 Tribeca Film Festival and Best International Documentary at BritDoc 2006. BONNEVILLE, a feature film starring Jessica Lange, Kathy Bates and Joan Allen as old friends who ‘come of age’ for a second time on a trip across the great American West. Errol Morris’ Oscar winning film THE FOG OF WAR: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara (acquired by Sony Picture Classics), which premiered at the 2003 Cannes Film Festival. THE STATION AGENT with director Tom McCarthy. STEVIE (acquired by Lions Gate Films), a critically acclaimed documentary by Oscar nominated HOOP DREAMS director Steve James.

May founded SenArt Films in August of 2000. Prior to the formation of SenArt Films, May was President of a nationally recognized security firm.

Bijan Tehrani: Kids For Cash is a very difficult film to make because it deals with a very delicate subject. How did you approach this film, and how did you come up with the idea of making it?

Robert May: Well, my producing partner and I were developing a fictional story about greed, power, and kids. When the scandal hit in January 2009, and it was literally ripped from the headlines and I was reading everything I could find about it. It made it onto the national news and the front page of the New York Times, and it made the guardian in London. It was one of those stories that just captivated people who wondered how these judges could literally just lock these people up for money. The other thing is that I have a home in Pennsylvania in the same community where these judges were actually from, and I think between those two things it just seemed like a natural project for us. We put aside—for the time being—the development of our fictional film, because we had a real life non-fictional version of the film right then-and-there.

BT: The amazing part of this film is bringing these facts to light without taking sides and instead allowing the audience to judge. How did you approach this?

RM: First, I want to thank you for that comment because as a filmmaker that means a lot. Even the last non-fiction film we did was called The War Tapes, and that is what people said about that. I think that a part of it is that I don’t like preachy films. I don’t like films that necessarily teach or preach; I want to be captivated by characters and I want to form my own opinion as a moviegoer. I thought that this story was perfect for that because we start out with a very one-dimensional story—because the media portrayed a one-dimensional story—and these judges who were perhaps ‘born evil’ because of this scheme they facilitated their whole careers. I was generally interested in how it could all happen, so that is the approach I took and I could tell you that when I would meet kids and families and then interview one of the judges, we went in without any judgment. We did not know what happened and we were not pretending to know; the demeanor of our team was that we were not here to judge and we were just there to tear the layers away, and I think that is why we achieved such great access.

BT: How have people involved in the film reacted to it?

RM: The judges are in a Federal system, so they will never get to see this movie. There is a law that states that a federal inmate cannot profit financially from any work  about their life or crime and they cannot psychologically benefit either, so the chances of them seeing the film is not likely. The judge’s daughter did see the film and all of the families and children have seen the film. No one knew who we were interviewing and certainly no one knew that we were going to be interviewing the judges, so when we screened the film for the families and let them know that the villains that they know were going to be featured in the movie, we talked them through it and we saw an ark about them in terms of how they felt. It was interesting to me because even the other side has empathy for one another and what they went through. The families feel that the film has allowed them to move forward with their lives and that was an extra bonus for us because we could not have imagined that this would happen.

about their life or crime and they cannot psychologically benefit either, so the chances of them seeing the film is not likely. The judge’s daughter did see the film and all of the families and children have seen the film. No one knew who we were interviewing and certainly no one knew that we were going to be interviewing the judges, so when we screened the film for the families and let them know that the villains that they know were going to be featured in the movie, we talked them through it and we saw an ark about them in terms of how they felt. It was interesting to me because even the other side has empathy for one another and what they went through. The families feel that the film has allowed them to move forward with their lives and that was an extra bonus for us because we could not have imagined that this would happen.

BT: Your background, having directed or produced film like “The War Tapes” and “The Fog of War”, helped you bring a very cinematic structure to this film. How did you come up with the visual style of this film?

RM: Thank you for that observation. The kind of films that I am interested in are films with point and reason. As a filmmaker, you want to find out how to entertain an audience on a tough subject matter. In this case we have the villain and the victim, and one of the critics of the film said that she had never seen a film that pits the villain and victim against one another so effectively. Some things just came out of inspiration through the interviews we did with the victims, and we needed to figure out a way to portray the film through the perspective of the children because they are telling a story that happened years ago. So the film was inspired out of the raw emotion of the kids and family members. A lot of the events took place in winter, so we wanted to match that feeling on screen as well.

BT: How did you go about working with the kids and getting them to tell their story on camera?

RM: The story of Amanda is interesting. When we were trying to figure out which kids to interview, we spoke to their relatives. But when it came to Amanda, her aunt told us that she was not really willing to talk to anyone; she was just closed about. So I took a shot at talking with her, and she agreed. We created an intimate atmosphere so it was just a conversation and she could only see my producing partner and me. We tried to create a safe place, and for the first time ever she told her story to us. That is why there is so much raw feeling and emotion. She told us that by telling us her story we kind of saved her life, which was amazing and also chilling to me.

BT: What is the next project you are working on?

RM: This was supposed to be a two-year project and because of the complexity of it and the 600 hours of footage, it took about 5 years to complete—and it changed my life. For my next project, I only want to do something that means something to me.