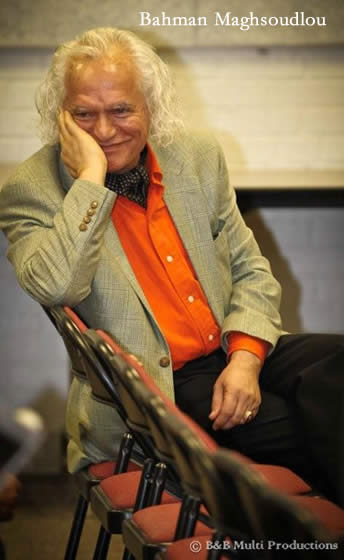

ABBAS KIAROSTAMI, A REPORT is a film by Bahman Maghsoudlou about the world known Iranian filmmaker, Abbas Kiarostami, his work and his world. Film scholar and critic Bahman Maghsoudlou is the recipient of Iran’s prestigious Forough Farrokhzad literary award for writing and editing a series of books about cinema and theater. These include the widely acclaimed Iranian Cinema, which was published in 1987 by New York University’s Center for Middle Eastern Studies. Maghsoudlou’s activities involving international cinema further include participation as panelist, juror and lecturer at a wide variety of film festivals, as well as serving as president of the jury at the 2012 Ibn Arabi Film Festival (IBAFF) in Spain and Montreal World Film Festival, 2014. As a filmmaker he wrote, directed and produced the short documentary film Ardeshir Mohasses and His Caricatures (1972), which was shown at the Leipzig Film Festival in 1996, Ahmad Mahmoud: a Noble Novelist (2004), and Iran Darroudi: the Painter of Ethereal Moments (2010). His latest two films, the fifth and sixth in the great Iranian artist’s series, are Ardeshir: The Rebellious Artist (2012), an extended update of his original film about Mohasses, and Abbas Kiarostami: A Report (2013), which is the first part of history of Iranian Cinema ,premiered at Montreal World Film festival. Having organized the first-ever Iranian Film Festival in New York in 1980, he originated the International Short Film Festival: Independent Films in Iran, which was held in October 2007 in Asian Society in New York.

ABBAS KIAROSTAMI, A REPORT is a film by Bahman Maghsoudlou about the world known Iranian filmmaker, Abbas Kiarostami, his work and his world. Film scholar and critic Bahman Maghsoudlou is the recipient of Iran’s prestigious Forough Farrokhzad literary award for writing and editing a series of books about cinema and theater. These include the widely acclaimed Iranian Cinema, which was published in 1987 by New York University’s Center for Middle Eastern Studies. Maghsoudlou’s activities involving international cinema further include participation as panelist, juror and lecturer at a wide variety of film festivals, as well as serving as president of the jury at the 2012 Ibn Arabi Film Festival (IBAFF) in Spain and Montreal World Film Festival, 2014. As a filmmaker he wrote, directed and produced the short documentary film Ardeshir Mohasses and His Caricatures (1972), which was shown at the Leipzig Film Festival in 1996, Ahmad Mahmoud: a Noble Novelist (2004), and Iran Darroudi: the Painter of Ethereal Moments (2010). His latest two films, the fifth and sixth in the great Iranian artist’s series, are Ardeshir: The Rebellious Artist (2012), an extended update of his original film about Mohasses, and Abbas Kiarostami: A Report (2013), which is the first part of history of Iranian Cinema ,premiered at Montreal World Film festival. Having organized the first-ever Iranian Film Festival in New York in 1980, he originated the International Short Film Festival: Independent Films in Iran, which was held in October 2007 in Asian Society in New York.

As a producer Maghsoudlou’s films have been selected for more than 100 major film festivals and garnered many awards, and include The Suitors (Cannes, 1988), Manhattan by Numbers (Venice, Toronto, London, Chicago, 1993), Seven Servants with legendary actor Anthony Quinn (Locarno, Montréal , Toronto, 1996), Life in Fog (1998)–the single most awarded short documentary film in the history of Iranian Cinema, and Silence of the Sea, winner of six prizes, selected for more than 20 other film festivals including the Sundance Film Festival in 2004.

Maghsoudlou is currently producing and directing a feature-length documentary on The Life & Legacy of Mohammad Mossadegh. Maghsoudlou’s new book, following such well-received titles as Iranian Cinema, Love & Liberty in Cinema and This Side of the Mind & the Other Side of the Pupil, is Grass: Untold Stories, a definitive account of the making of Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life, the groundbreaking documentary filmed by Merian Cooper, Ernest Schoedsack and Marguerite Harrison in Iran in 1924. He is a member of Pen American center. A graduate in cinema studies from the City University of New York with a PhD from Columbia, Maghsoudlou lives in New York.

Bijan Tehrani: What motivated you to make ABBAS KIAROSTAMI, A REPORT?

Bahman Maghsoudlou: I started to interview people who worked in Iranian Cinema before the revolution in Tehran in 2002. In fact, this monumental project started with a trip that took me to Iran and Europe, along with various stops around the United States. I interviewed more than 120 people, directors, writers, actors, cinematographers, critics, producers, film historians and many more. I wanted to make a history of Iranian Cinema before the revolution and convey how that cinema had both commercial and artistic independent films, and how around 50 of those independent films served as the basis of the Iranian Cinema after the revolution that blossomed and captured the eyes of cineastes around the world, garnering a lot of various international awards. After having made films about Ahmad Shamlou (a poet), Ahmad Mahmoud (writer), Iran Darroudi (painter), and Ardeshir Mohasses (caricaturist), I reached a point where I realized it was time to start working on this film, History of Iranian Cinema: Searching for the Roots¬, in earnest. But by that time, the project had become so vast, with all the assorted interviews, that I realized I had enough material to make 10 different films in a collection/series.

Abbas Kiarostami, among Iranian filmmakers, is the most important and the most influential. He has established himself as one of the world’s best directors and is known all over the planet. In fact, after Rumi, Ferdowsi, Sa’di, Hafez, and Khayyam, the great Iranian poets, his is probably the most recognizable name of an Iranian artist around the world. In two surveys conducted at the end of the ‘90s by groups of international film critics and film historians, Kiarostami was selected as the world’s most important filmmaker. He was selected in another survey in 2006 by The Guardian’s panel of critics as the best contemporary non-American film director. As a result, I decided to make a film about his cinema, style and vision, and why Abbas Kiarostami became so successful as an auteur in world cinema.

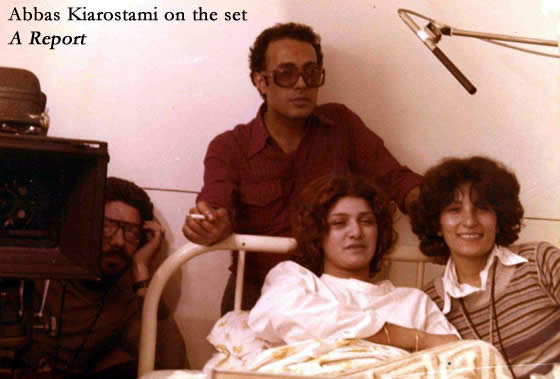

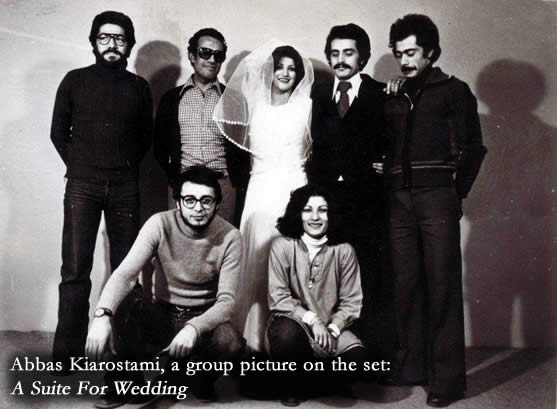

Kiarostami was among numerous Iranian directors before the revolution who made both shorts and  feature films that brought Iranian Cinema to the attention of a few major film festivals around the world. His first feature film, The Report, was the last major film to be released before the revolution, opening in theaters just a few months before it all began. This film was well received by critics and cineastes in Iran but its run was short-lived because the extremists were burning movie houses. Although Kiarostami’s films and his name became well known after the revolution and he has received hundreds of awards and prestigious prizes, The Report was never available to be released and was not be part of his major retrospective. Nobody knew the fate of the print of this movie or its whereabouts. Apparently, the rumor was that the government had destroyed the print at the beginning of the revolution. This was the first time I was making a documentary that was related to my education as a film critic and a film historian. I decided to deal with Kiarostami’s style and vision, his and his cinema’s place in the world, and the reason why he has managed to come such a long way in the film world.

feature films that brought Iranian Cinema to the attention of a few major film festivals around the world. His first feature film, The Report, was the last major film to be released before the revolution, opening in theaters just a few months before it all began. This film was well received by critics and cineastes in Iran but its run was short-lived because the extremists were burning movie houses. Although Kiarostami’s films and his name became well known after the revolution and he has received hundreds of awards and prestigious prizes, The Report was never available to be released and was not be part of his major retrospective. Nobody knew the fate of the print of this movie or its whereabouts. Apparently, the rumor was that the government had destroyed the print at the beginning of the revolution. This was the first time I was making a documentary that was related to my education as a film critic and a film historian. I decided to deal with Kiarostami’s style and vision, his and his cinema’s place in the world, and the reason why he has managed to come such a long way in the film world.

BT: Did you have a script before starting to shoot the film? Your film has a strong structure, how did you come up with it?

BM: No, I didn’t have a script. But I knew what I wanted to make. I wanted to prove the theory stated by Bazin and Godard that, in cinema, you can do everything, and that Kiarostami unconsciously followed that idea.

Using the excerpt of his short film The Road (2007) at the end of the film seemed to be the best conclusion for illustrating this. It shows Kiarostami’s journey in asphalt, which then becomes sand, and then ramparts, and then a small road, and narrow and narrower, but at the end, he reaches a home or a destination from which there are other roads available as well.

BT: Watching this film, I was thinking that you must have needed to have watched Kiarostami’s films a few times to have such a good understanding of his work. Please tell us about pre-production and research stage of “Abbas….”

BM: Yes, of course. I have been a film critic since I was 15 and I started to write about films while I was still in Iran. I was the only Iranian film critic and one of just four Iranian people (Mohsen Makhmalbaf and Alireza Shojanouri from Iran, and Reza Pakzad, cinematographer for Amir Naderi’s Water, Wind, Sand, who had come from Denmark) at the Locarno Film Festival in 1989 when his film Where Is the Friend’s House? was in competition. My book about Iranian cinema had just been published by New York University Press and it was the first book in English about the subject. Most of the jurors were reaching out to me, asking about Kiarostami and his back ground. I was very happy that the film received the Bronze Award at the festival. And then, in 1990, I was among the foreign guests at the Fajr Film Festival that watched Close Up, his best film. In fact, I was privileged enough to witness how Kiarostami came to the world scene from 1989 to 1992, when the second part of his koker trilogy, Life and Nothing More, came to the Cannes Film Festival . I was there and experiencing his ascension.

As far as my movie goes, I had to watch his films a few times and find everything related to his cinema and as many clips from anywhere as I could. I was lucky that a friend of mine who was the head of a museum and film library sent me a good quality copy of The Report. Nobody had it, and even with this print, one scene was missing, the one in which Firuzkuhi and his wife make love. I tried hard to find it, but …

I was only able to find four behind-the-scenes production stills after a lot of hard research and calling a lot of people. Fortunately, I was working with three editors with good taste. I mapped out what I want, how the film should start and how I wanted to end with the shots from The Road. Also I wanted to highlight the most difficult scenes that Kiarostami and his crew encountered. It took almost one year to edit this film and finalize it. I am very happy with the result.

BT: When you got in touch with Abbas Kiarostami about making this film, how did he react?

BM: I knew Mr. Kiarostami from the early ‘70s in Iran and from his works at Kanoon. During the making of Shamlou, I had a meeting with him in Paris just after he received the Unesco award in 1997 and convinced him to talk about Shamlou. He graciously did it on the condition that he would film his own segment and we would add it to the film as is. In fact, that segment was one of the best in my production. Then, in 2002, when I was in Tehran for a month doing all the interviews on the history of Iranian Cinema, I tried to nail him down for another filmed interview, but he wouldn’t do it, saying I should go ahead and work on the film and he would sit down with me at some time later time. And later it was. It took almost five years of persistence on my part, contacting him in locations all over the world, before he finally agreed and asked me to send him the questions I wanted to ask. By that time, I had offered to limit my questions to the production of The Report. He filmed himself talking about that movie and sent the tape to me in New York through my beloved brother Behrouz. At that time, I was still uncertain as to the form I wanted the film on Iranian cinema to take. That all changed after I went to the IBA Film Festival in Murcia, Spain to serve as president of the Jury. By good fortune, Kiarostami was spending two weeks in a workshop at the same festival, so and we spent one week together there, talking a lot. It was during that time that I realized that project should be a series of films instead, and that the first part should be about Abbas Kiarostami and his contribution to the history. I came back to New York and began editing it immediately.

BT: What is it like conversing with Kiarostami in person?

BM: He is a lovable person, very clever, quiet and well mannered. He pays attention to all the details around him, and respects all, listening quietly and respectfully, even to opposing opinions about his ideas or his films. He is a unique person.

BT: How did you select the film critics and actors that talk about Kiarostami in your film?

BT: How did you select the film critics and actors that talk about Kiarostami in your film?

BM: When I started the Iranian cinema project in 2002, I immediately made a list of esteemed film critics from around the world who I hoped to interview. Fortunately, most of them knew me through my works as producer and my own film criticism, and so they agreed.

Regarding the Kiarostami film, I had already interviewed Yousef Shahab and Shohreh Aghdashlou, but not Alireza Zarindast and Kurosh Afsharpanah, the lead actor. I had met Afsharpanah in London and was able to arrange a trip there so I could interview him, and I sent questions to Tehran to Zarindast and arranged the interview with him too. The rest of the interviews were conducted during 2002 and 2006. I also decided to interview Michel Frodon in Paris, because he is another great film critic and because the pieces he had written on Kiarostami had been so wonderful and important.

BT: How challenging was making this film?

BM: It was quite a challenge to make a documentary about a great filmmaker and auteur who has been selected as being the best non-American director by critics. I felt like I had to make a film that had a strong kinship with Kiarostami’s own canon that was in line with his style. To use music like he uses, cut my film as he cuts his films. And to continue to honor the cinematic notion of Bazin and Godard that I mentioned earlier. Kiarostami is an observer and recorder of all the details of life, which he stores in his memory. He stands outside and looks around carefully at the entirety of whatever event is happening around him. I opened the film with a sequence showing one of his heroes going to the cinema and seeing a portion of Kiarostami’s most recent film, which served as a jumping off point to go back to his earliest. The hero as alter-ego of the director is the point of view from which I edited the film. Shirin is, perhaps, his most important film because he captured the reactions of around 118 actresses in remembering their experiences, good and bad, being in front of his camera. It is the key to his cinema and nobody has noticed that. I tried to disperse various shots of Shirin throughout the film, along with shots of my critics’ faces to reinforce the concept and bring a piece of his way of filming to my film. Also, because The Report is his first real feature film, and is arguably the best film made before the revolution, it made sense to make that the main film to put on the anatomy table to display the various aspects of his work. The other films mainly serve to complete my argument.

BT: Has Abbas Kiarostami seen the finished film? If so, what was his reaction to it?

BM: At first, he did not want to see it. Generally, he does not watch material about himself. But after six months, he asked me to send him a DVD to look at. Still, when he got it, he gave it to one of his close friends, a famous photographer and filmmaker, to look at first and report to him. When his friend told him was a good film, then he looked at it and liked it very much. He has even started to screen it at his workshops, and it has received a lot of good feedback in those as well. Kiarostami then called me and thanked me and sent me the following comment: “Since it would be improper for me to comment on the quality of a film of which I am the subject, let me just say that anyone who watches this film will come away having learned a lot.”

BT: This is a very interesting and entertaining film that provides an amazing knowledge about Abbas Kiarostami’s filmmaking. What has been the reaction from audiences and film critics?

BM: The film successfully opened at the Montreal World Film Festival on September 2013 and was very well-received.

It then went to other film festivals around the world and was also screened at the Cineteca Nationale in Rome in October 2014. It has already become part of the curricula at a few universities, like Boston University, which will screen it on April 23 as part of their Anthropology and Cinema in the World program.

The film was part of a Kiarostami retrospective in early 2014 at Indiana University entitled So Much to Teach, and was also shown at the MESA Film Festival of the same year. Generally speaking, all of the audiences around the world who have sat for it, cineastes and film critics alike, have given it a very enthusiastic reception. Video Librarian Magazine in USA reviewed the DVD and recommended it, giving it three out of four stars. I have a few blurbs by critics:

1-[A] beautiful film that is also a lesson in filmmaking!

-Molly Haskell

2-Bahman Maghsoudlou’s movie about Abbas Kiarostami is certainly one of the best if its kind ever realized.

-Pierre-Henri Deleau

3-…I believe this is an excellent work…

-Jean-Michel Frodon

4-Authoritative and incisive…a novel, probing and highly illuminating look at the work of one of the modern cinema’s greatest masters.

-Godfrey Cheshire

5-Kiarostami’s most serious admirers will appreciate its insights into the challenges faced on his first feature-length production.

-Hollywood Reporter

6-…draws analytical attention to Kiarostami’s humanism and constant quest for peace and reconciliation in a world wounded by perpetual conflict and hate…

-Amir Taheri, Asharq Al-Awsat

7-Maghsoudlou has made one of the smartest docs on a filmmaker I’ve seen in a long time…

-Dejan Nikolaj Kraljacic, Filmfestivals.com

8-It’s a well-crafted “report” in its own right, and a valuable contribution to a neglected subject, the history of Iranian cinema. “

-Jonathan Rosenbaum, film Critic

9-…It’s a valuable resource for all students and educators, and anyone else who is interested in Kiarostami’s cinema.

-Mehrnaz Saeedvafa,

Professor of film at Columbia College, Chicago

BT: Please tell us about your future projects

BM: I am editing two feature documentaries that will serve as Parts Two and Three of the History of Iranian Cinema. Part Two is Legacy of the Iranian Actress and Part Three is The Cow: It’s Impact on Iranian Cinema.

The Life and Legacy of the Iranian Actress, the second film in this series, is my priority project at the moment, and I hope to edit and release it as soon as possible. It examines the lives and impact of twenty of the most prominent actresses to work in Iranian cinema before the revolution, from Rouhangiz Kermani (Saminejad) who played the title character in Dokhtare Lor (The Lor Girl) in 1932 to Gougoush the international pop star. Iren , Zhaleh, Shahla, Zari Khoshkam, Katayun ,Zinat Moaadab , Shahrzad , Susan Taslimi, Fahime Rastgar, Parvaneh Ma’sumi, Shohreh Aghdashlou, Farzaneh Taidi, Mary Apick are among those who have been interviewed. This feature documentary deals with how, in a traditional, religious and male-dominated society, actresses dared to assert themselves within the relatively new art form, sacrificing to bring modernity to the culture and force acceptance of their presence in the cinema.