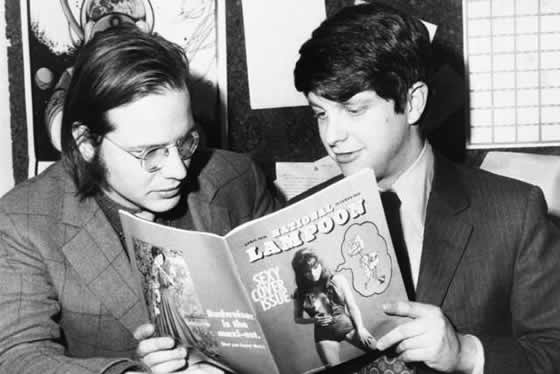

From the 1970s thru the 1990s, there was no hipper, no more outrageous comedy in print than The National Lampoon, the groundbreaking humor magazine that pushed the limits of taste and acceptability – and then pushed them even harder. Parodying everything from politics, religion, entertainment and the whole of American lifestyle, the Lampoon eventually went on to branch into successful radio shows, record albums, live stage revues and movies, including ANIMAL HOUSE and NATIONAL LAMPOON’S VACATION, launching dozens of huge careers on the way.

From the 1970s thru the 1990s, there was no hipper, no more outrageous comedy in print than The National Lampoon, the groundbreaking humor magazine that pushed the limits of taste and acceptability – and then pushed them even harder. Parodying everything from politics, religion, entertainment and the whole of American lifestyle, the Lampoon eventually went on to branch into successful radio shows, record albums, live stage revues and movies, including ANIMAL HOUSE and NATIONAL LAMPOON’S VACATION, launching dozens of huge careers on the way.

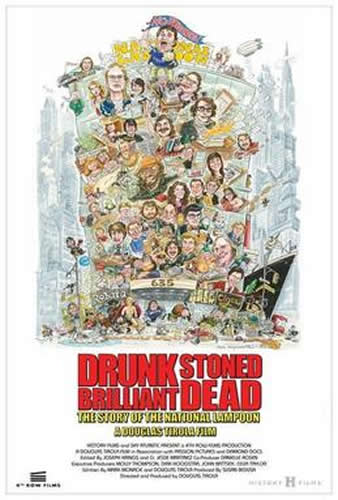

Director Douglas Tirola’s documentary DRUNK STONED BRILLIANT DEAD: THE STORY OF THE NATIONAL LAMPOON – tells the story of its rise and fall through fresh, candid interviews with its key staff, and illustrated with hundreds of outrageous images from the mag itself (along with never-seen interview footage from the magazine’s prime). The film gives fans of the Lampoon a unique inside look at what made the magazine tick, its key players, and why it was so outrageously successful: a magazine that dared to think what no one was thinking, but wished they had.

Bijan Tehrani: Making a film about National Lampoon is such a difficult subject to make, it’s like making something about God because you have heard so much about it and it is everywhere and at the same time you don’t see it. What was your motivation to make this film?

Douglas Tirolai: I think that my introduction to the Lampoon was through Animal House, and then that led me to the magazine and the records, so obviously, I liked Animal House. I didn’t realize how influential it was for me until a few years ago in my behavior. People would commonly say that I take things too far in the way that I would express myself. Not because of any profanity, but the point I am trying to make or things that I am pointing out, or the willingness to point out certain hypocrisies or when I think that something is wrong. I still have some of the Lampoon books and magazines from when I was a kid, and I started looking through them, and that’s when I realized that maybe Lampoon had shaped my worldview more than I would have known. So I thought the story of National Lampoon would make a great movie because it was a story that resonated on people that knew a little bit about it, but they didn’t know the real story. My film is not just a tribute to the artists that worked for the magazine. As a filmmaker, not that I am looking for movies that have the same theme, but I started to recognize that my films have some common themes to them. So for me, two of them are in this, which one is about work. I view work as a positive thing. I think a lot of documentaries movies view work as the enemy, and I think that work is the best thing that ever happened to the people working at the Lampoon. I think for most of them, it was the best experience of their life, or at least a very special experience, and that attracted me to it. Then this idea of people who are very dissimilar working together, that attracted me as well. People—it is very much like working on a movie. You work on a movie, and you almost never would be friends with these people under any other circumstance. If it wasn’t for work, you wouldn’t be together, and the Lampoon I think is an extreme example of that, and I am attracted to that.

was a kid, and I started looking through them, and that’s when I realized that maybe Lampoon had shaped my worldview more than I would have known. So I thought the story of National Lampoon would make a great movie because it was a story that resonated on people that knew a little bit about it, but they didn’t know the real story. My film is not just a tribute to the artists that worked for the magazine. As a filmmaker, not that I am looking for movies that have the same theme, but I started to recognize that my films have some common themes to them. So for me, two of them are in this, which one is about work. I view work as a positive thing. I think a lot of documentaries movies view work as the enemy, and I think that work is the best thing that ever happened to the people working at the Lampoon. I think for most of them, it was the best experience of their life, or at least a very special experience, and that attracted me to it. Then this idea of people who are very dissimilar working together, that attracted me as well. People—it is very much like working on a movie. You work on a movie, and you almost never would be friends with these people under any other circumstance. If it wasn’t for work, you wouldn’t be together, and the Lampoon I think is an extreme example of that, and I am attracted to that.

BT: There are a lot of people that have been directly or indirectly influenced by National Lampoon’s kind of humor. I would even say that when you are looking at Saturday Night Live or Bill Maher or even Jon Stewart, you find the kind of humor that started with National Lampoon. What do you think about that?

DT: I think Bill Maher, when Bill Maher with some of his commentary, and he has the segments on his show that are written in advance. There is definitely a link between him and National Lampoon. I would say Howard Stern has a link. He is clearly influenced by National Lampoon in that era. The Daily Show I think to some extent, but the Daily Show I think at a certain point you kind of knew what you were going to get with it, like if there was a topic that came up. I think it became increasingly rare that you didn’t know what direction they were going to go. Colbert, of course, is a great parody in general, but the same thing, it is always the same point of view over and over. Lampoon—though the staff probably wasn’t politically diverse—overwhelmingly liberal—they would still have more willingness to go after anybody.

BT: Also, when I looked at the list of people that you have interviewed for the film, I said “Oh my God, another talking head movie,” but when I looked at your film, it wasn’t at all like that. First of all, I really loved the idea that interviews were mostly shot in long shot and not close ups, and then it was kind of related to giving a back story about people in the film.

DT: I really appreciate you for saying that. I approached it as I do any of the movies, even though they are documentaries—to approach it like a scripted—like it is a screenplay. Meaning, it is just like working with actors. You kind of have this screenplay, and you have to get certain points out to have the story make sense, but of course you are hoping something unexpected happens and it takes you in a little bit of a different direction. The reason I chose to do the talking heads just because if I was to give more time to who they are now or what they are doing now, even though some of that is interesting and certainly seeing the ones who have gone on to be successful are interesting and to see what it has led to, but it takes you out of the era. Anything that I would do that would cause focus on today takes you away from the seventies and the early eighties with this story, so that’s why I chose that.

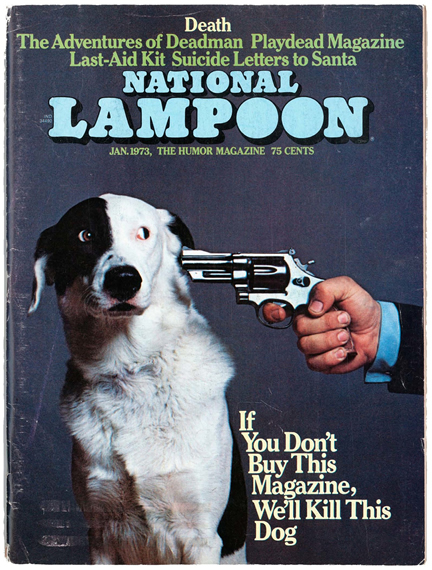

BT: I think it was very successful also with the visual references that you used from the actual magazine, which worked really well.

DT: You are exactly right. That’s a way again that can make you feel, especially for younger people who have never held a magazine or maybe didn’t know it exists. I think they come away from it thinking like, “Wow, I have a real feel for that magazine now.” I hope.

BT: Do you think your film can help to bring National Lampoon Magazine to life?

DT: I would hope that the people running the National Lampoon now would see that the movie is going to create some desire for people to go back and revisit the magazines, and I think even the magazines because they are such a time capsule, even looking at the advertisements that were in the magazine at the time, there is some value to. I would hope that they think about doing something that puts the magazine back into kids’ hands. For me, the movie, if someone asked me what some of the movies I am thinking about doing next are, and they all have to do with politics, which I am sure that if someone is paying attention, would lead them to understand that there is much more politics in this film going on than meets the eye. What that is for me is that the movie itself is a political statement, and what I mean by that is that I am hoping, especially when young people watch it, they go “Wow, we really don’t have anything like this today. We don’t express ourselves this way. There are less words in our language. There is more fear about expressing what we really think.” So hopefully part of it will be that they will go find a Lampoon, and part of it will be that they create an environment where people are less afraid to really express themselves. As you probably know, freedom scares most people.

BT: Exactly. How did you find most of the people involved with the magazine and getting them to interview? How challenging was that?

DT: Oh my God, that is an insightful question—extremely. I produced (some of which I have directed) nine other documentaries. Most of the time, not all of the time, once you start doing the movie, people often times want to be in the movie. Once they get over the fear of “How am I going to look or sound,” they get over it. Nobody was in a big rush to be in this movie. Most of the people in it didn’t want me or anybody else to make the documentary about it. They didn’t think it could be done or could be done well. So I would equate it much more to the experience one has when you are trying to make a scripted movie, and you are trying to get actors to be in it. We have to convince them just to read it, and try to get a performance out of them. So it was definitely a challenge to get the movie made, especially when you needed these people to be in interviewed to tell the story. I didn’t want to have a bunch of biographers. There are about three good books written about the Lampoon, and I didn’t want to have those people telling the story. I didn’t interview them, as well, but the only people we interviewed who didn’t work at the Lampoon were fans. We were trying to talk about the magazine when they read it or when they saw the movies, not trying to give commentary about how it compares to now. I am hoping the audience will compare how it is to now.

BT: Are you working on any new projects?

DT: I am. I am producing a few. I am producing one that is very serious about a woman who is the first person to kill herself on TV called “Kate Plays Christine.” I am producing one about toys, about the current phenomenon of toys and how many adults buy toys. Toys are just booming right now. Then the ones I am looking at directing, one has to do with political cartoonists. I don’t know if you are a newspaper reader, but political cartoons are a dwindling field. Newspapers are having so many challenges. There is a very small community of political cartoonists we are dealing with, and then speechwriters. I am doing something about presidential speechwriters. I am also looking at a couple other fun ones that have to do with maybe an actor or an artist, but we are still figuring that out.