When we are exploring the effects of specifically gender-coded characters in the cinema, we are reminded of the very fundamental question about the effect of a movie on its spectator: Is it the movie that dictates the behaviors of society or is it society that dictates the behaviors in a movie?

When we are exploring the effects of specifically gender-coded characters in the cinema, we are reminded of the very fundamental question about the effect of a movie on its spectator: Is it the movie that dictates the behaviors of society or is it society that dictates the behaviors in a movie?

As far as exploring the relationship between gendered characters (i.e. a character who is specifically skewed as either completely feminine or masculine, and has very few androgynous qualities otherwise) we must question the purpose for that skew, as most people are not completely masculine or feminine, but rather a healthy blend.

Perhaps when we are viewing a film and we relate to a character or slip into that escapist world where we ‘pretend’ we are a certain character for a while, we should step back and look at the character’s purpose in the film as well as its effect on us, the spectators.

Jamie Babbit’s Itty Bitty Titty Committee is a film about a group of lesbian-identified women taking on the oppressive male-dominated society through radical guerilla tactics.

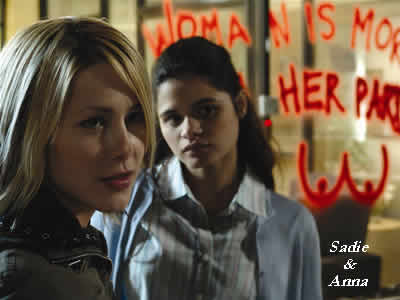

So then are we to assume that when Ms. Babbit created the radical feminist characters, which the typical female spectator cannot relate to in the first place, her intention was to actually capture the realistic experience of her target audience? Or perhaps this was a conscious decision to influence the spectator with the thoughts she passed through her main character, Anna (played by Melonie Diaz)?

cannot relate to in the first place, her intention was to actually capture the realistic experience of her target audience? Or perhaps this was a conscious decision to influence the spectator with the thoughts she passed through her main character, Anna (played by Melonie Diaz)?

When the group of characters in the film choose to reclaim public space in the name of women all over the world, the plot pushes into a less relatable series of events and forces the spectator to become more of a witness to the film, rather than an ‘active’ participant in an escapist cinema.

What are we to get out of this through gender? Chances are that those strong supporters of the film’s ideology are already relating to Anna’s character and see her as similar to themselves, if not desirable to be like (hence a strong support deriving from a more complete experience of escapism). However, there is nothing new to get out of completely relating to something. There must be a new element that allows a spectator a new view of a familiar world.

This leads us to the spectators that don’t initially have a strong opinion of Anna or the presented ideology either way. Rather, their basis of overall enjoyment of the film will come from whether they will be able to slip into the synthetic world of the cinema

This leads us to the spectators that don’t initially have a strong opinion of Anna or the presented ideology either way. Rather, their basis of overall enjoyment of the film will come from whether they will be able to slip into the synthetic world of the cinema

The need to ease the spectator into this world is the one reason why love is the universal theme in the narrative cinema. A spectator knows love and as such, is familiar to it. As such, the ‘relatable’ section of this film to most spectators is found in the romantic interests of Anna and her relations to Sadie (played by Nicole Vicius), essentially utilizing this element as the hook.

If the spectator is hooked with something interesting, such as a romantic story, the filmmaker can then push their ideology onto the more responsive mind of the spectator. In a sense, it is the same method as advertising a product: Entertain, comfort, and intrigue the viewer, while simultaneously selling the product to them.

Gender-coding is one element that helps to further sell a film’s product: the ideology. Anna is simply the bridge to help the viewer feel entertained, comfortable, and intrigued. Once in this state, the spectator opens herself up to possibly accepting a more radical idea, and as such, allows a message of feminist thought to be enter their mind, which might not have any opinions on the subject prior.

The difficulty of this film, however, lies in Anna’s sexuality. Since she identifies as a lesbian, certain members of the primarily female audience might be driven away due to unfamiliarity or discomfort. In this sense, the gender of the character (female) is overshadowed by her sexuality (lesbian), and might ostracize certain spectators from ever getting to the actual product (feminism), which Jamie Babbit is clearly presenting.

Consider dropping this ideology into any modern romantic-comedy. You already have the attention of a broader female spectator-base than the queer cinema audience, allowing a higher number of spectators to be receptive of such ideology. While they might not hold feminist thought in as high of a regard as the core demographic for Itty Bitty Titty Committee, they will most likely accept the ideas if presented convincingly.

Queer cinema is undeniably not as widely accepted as the mainstream cinema. To make a film about issues important to you and only intend to show them to people similar to you will change very little in this world. You’d only be ‘preaching to the choir’, so to speak. It is the filmmaker that braves the unknown territory and brings a message to people that have a different view than you.

people similar to you will change very little in this world. You’d only be ‘preaching to the choir’, so to speak. It is the filmmaker that braves the unknown territory and brings a message to people that have a different view than you.

Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain took a story about two men falling in love, and made it undeniably beautiful and warm, regardless of the spectator’s previous opinions. Steeped in the heavily gender-coded genre of the Western, this film still chose to deal with homosexuality. It took the familiar aspect of love and allowed the typical spectator to latch on to that element, and then be shown a new world within a familiar concept.

It’s unfortunate that homosexuality in the cinema has to still be the ideology that needs to be sold to the mainstream spectator, rather than one of the familiarizing points, but the filmmaker must take into account the small reach they will get with their message if they push too far for that perfect utopian society where everyone is equal. The spectator is reluctant to change. The filmmaker must know that and ease this change into them, rather than throwing it in their face.

Itty Bitty Titty Committee’s intended demographic was undoubtedly the female intellectual, who most likely had at least some previous exposure to feminist thought, but never truly saw the ideology in action. Unfortunately, Anna’s gender, as a selling point for this ideology, was overshadowed by her own sexuality. What could have been about women fighting for women all over the world became a convoluted story that tried too hard to fit into the queer cinema. While still an entertaining film, Itty Bitty Titty Committee nonetheless fails to make any real waves, as it is selling an ideology that its actual demographic had already bought.