The Poetry of Everyday Life: Picture Virgil and Horace spooling their lyrical dramas and tales a millennium later on the streets of Rome. Once telling of mortals sacrificing their children to the gods and carrying their fathers on their shoulders across the seas surrounding Italy or feuding with jealousies and infidelities of their own, the eloquent verses take to city traffic and crank themselves out in mid-20th-century images. The betrayals and crimes, loyalties and desires, are still there, and so are the ashes of war; but the gods are fascists and the mortals are men on bicycles riding to work, shoeshine boys prancing high upon a horse, mothers protecting their daughters from soldiers, until….

streets of Rome. Once telling of mortals sacrificing their children to the gods and carrying their fathers on their shoulders across the seas surrounding Italy or feuding with jealousies and infidelities of their own, the eloquent verses take to city traffic and crank themselves out in mid-20th-century images. The betrayals and crimes, loyalties and desires, are still there, and so are the ashes of war; but the gods are fascists and the mortals are men on bicycles riding to work, shoeshine boys prancing high upon a horse, mothers protecting their daughters from soldiers, until….

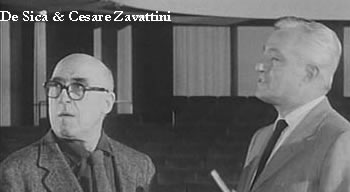

Imagine that the tragedy of war has come home. The drama has entered everyday life. The poetry is now a dance of shadows on a screen, and the dreams are seen like the veins of leaves. “The wonder must be in us, expressing itself without wonder.” At least this is how Cesare Zavattini put it, the writing partner and co-conspirator of Vittorio De Sica in the unique moment of film history that would be known far and wide as “neorealism.” The ritual is cinema, and while the art is one of dire necessity, achieved bare-handed with minimal means, its aim is the same — social solidarity, catharsis, the healing and transformative power of poetry-in-the-making.

And the Winner Is…

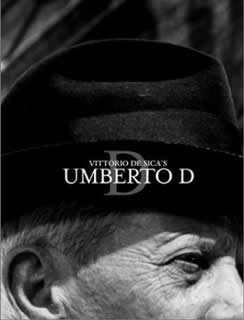

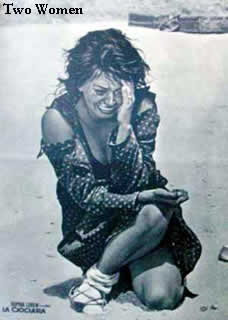

In 1971, three years before his death, Vittorio de Sica’s work was honored with an Oscar for the fifth time, after thirteen nominations for films he’d directed and one for his acting in Charles Vidor’s A Fairwell to Arms (1958). That last award was for the Best Foreign Language Film, The Garden of the Finzi Continis, and it was presented by Tennessee Williams (the film was also nominated for a Best Writing award). Before that, in 1964 Rex Harrison had handed the same Oscar to producer Joseph E. Levine for De Sica’s Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. Its leading actress, Sophia Loren, was nominated that year for De Sica’s Marriage Italian Style and had won the Best Actress Award for his Two Women three years earlier (the first time it was given for a foreign language role). A few years prior to that, De Sica’s long-time collaborator Ceasare Zavattini had finally been nominated for Best Writing for their homage to De Sica’s father, Umberto D. Almost a decade earlier the Academy’s Board of Governors had presented the team with a Special Foreign Language Film Award for perhaps their most famous work, Bicycle Thieves.

nominations for films he’d directed and one for his acting in Charles Vidor’s A Fairwell to Arms (1958). That last award was for the Best Foreign Language Film, The Garden of the Finzi Continis, and it was presented by Tennessee Williams (the film was also nominated for a Best Writing award). Before that, in 1964 Rex Harrison had handed the same Oscar to producer Joseph E. Levine for De Sica’s Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. Its leading actress, Sophia Loren, was nominated that year for De Sica’s Marriage Italian Style and had won the Best Actress Award for his Two Women three years earlier (the first time it was given for a foreign language role). A few years prior to that, De Sica’s long-time collaborator Ceasare Zavattini had finally been nominated for Best Writing for their homage to De Sica’s father, Umberto D. Almost a decade earlier the Academy’s Board of Governors had presented the team with a Special Foreign Language Film Award for perhaps their most famous work, Bicycle Thieves.

But it had all started two years before that, in 1947, before any Academy Award had ever been given for a film made in a language other than English. A groundbreaking work turned the heads of the Academy once and for all, De Sica’s and Zavattini’s stunning Shoeshine. Recognizing Italy for its promising ventures in cinema amidst the rubble of World War II, the Academy created a “Special Award” just to be able to salute the film, declaring, “The high quality of this motion picture, brought to eloquent life in a country scarred by war, is proof to the world that the creative spirit can triumph over adversity.”

But it had all started two years before that, in 1947, before any Academy Award had ever been given for a film made in a language other than English. A groundbreaking work turned the heads of the Academy once and for all, De Sica’s and Zavattini’s stunning Shoeshine. Recognizing Italy for its promising ventures in cinema amidst the rubble of World War II, the Academy created a “Special Award” just to be able to salute the film, declaring, “The high quality of this motion picture, brought to eloquent life in a country scarred by war, is proof to the world that the creative spirit can triumph over adversity.”

Places and Faces

De Sica came to cinema with two special gifts, and it was his father, Umberto, who noted them and insisted that the boy use them. First, the son possessed an innate charm as an entertainer. Even as a teen, Vittorio commanded quite an audience for his singing, but he was bent on becoming a bank clerk like his father who, luckily, had also been a journalist. So Vittorio studied accounting at a technical institute and then graduated from Rome’s University School of Political and Commercial Science. Little did he know that financial skills and a political sensibility would serve him well, but precisely for the film career that lay ahead, since his father tapped the entertainment celebrities he knew and launched the boy in a silent film that soon led to acting in Tatiana Pavlova’s theatre troupe and to forming his own company, producing plays and co-starring with his first wife, Giuditta Rissone.

insisted that the boy use them. First, the son possessed an innate charm as an entertainer. Even as a teen, Vittorio commanded quite an audience for his singing, but he was bent on becoming a bank clerk like his father who, luckily, had also been a journalist. So Vittorio studied accounting at a technical institute and then graduated from Rome’s University School of Political and Commercial Science. Little did he know that financial skills and a political sensibility would serve him well, but precisely for the film career that lay ahead, since his father tapped the entertainment celebrities he knew and launched the boy in a silent film that soon led to acting in Tatiana Pavlova’s theatre troupe and to forming his own company, producing plays and co-starring with his first wife, Giuditta Rissone.

A handsome figure of a man with a winning smile, Vittorio De Sica wore his suave manner like a birthright. Tall, dark, and debonair, he became a matinee idol (both comedian and crooner) in his early twenties. He mastered the art of acting by virtue of his own experience: in a span of 26 years he appeared on the stage in over 125 productions — this in addition to over 150 performances as a screen actor that continued through his entire life. Once he began directing films of his own (31 features, all told), De Sica preferred not to use professional actors, but the professional that he was, according to one Assistant Director, “he could lure even a sack of potatoes into acting.” Then he patiently guided both pros and amateurs of all ages by acting out every nuance and inflection of their roles according to his own interpretation and calling upon them to imitate him.

A handsome figure of a man with a winning smile, Vittorio De Sica wore his suave manner like a birthright. Tall, dark, and debonair, he became a matinee idol (both comedian and crooner) in his early twenties. He mastered the art of acting by virtue of his own experience: in a span of 26 years he appeared on the stage in over 125 productions — this in addition to over 150 performances as a screen actor that continued through his entire life. Once he began directing films of his own (31 features, all told), De Sica preferred not to use professional actors, but the professional that he was, according to one Assistant Director, “he could lure even a sack of potatoes into acting.” Then he patiently guided both pros and amateurs of all ages by acting out every nuance and inflection of their roles according to his own interpretation and calling upon them to imitate him.

A second gift from his family also served De Sica well. While he was born in 1902 in Sora, a small market town in the Ciociara countryside between Naples and Rome, De Sica moved to Naples just a few years later when the Banca d’Italia transferred his father there. Like Umberto, Vittorio felt a special affinity for Napoli for the rest of his life, but the family also moved to Florence a few years later, and to Rome five years after that. So in his formative years the boy grew up with three distinct “Italy’s” — the passion and humor of Naples, the aristocratic charm of Rome, and the cultural refinement of Florence. All would figure vividly in the dialects, dispositions, and temperaments of the characters in his films. And the director would come to discover and make special use of every nook and cranny of Rome, the “open city” of neorealism.

A Life of Paradox

Vittorio De Sica was known even in his lifetime as a man of contradictions. It was precisely the fare that came to repel him — the telephone bianco films of the 1930’s (trite pot-boilers and fluffy romances made artificially in studios, symbolized by the ever-present white telephone) — that brought him lucre as an actor that he would then turn around and use to direct the serious works that drew his commitment, films he could approach in a natural and organic way. Celebrity governed his own acting and theatrical style, precisely the stardom and style he shunned for the films he directed with “unfamiliar” faces according to the credo of neorealism.

1930’s (trite pot-boilers and fluffy romances made artificially in studios, symbolized by the ever-present white telephone) — that brought him lucre as an actor that he would then turn around and use to direct the serious works that drew his commitment, films he could approach in a natural and organic way. Celebrity governed his own acting and theatrical style, precisely the stardom and style he shunned for the films he directed with “unfamiliar” faces according to the credo of neorealism.

He made a film for the Vatican during World War II (which they rejected and destroyed), stretching out production until Rome was liberated by the Americans so that he could avoid being sent by Goebbels to direct a German film school in Prague or be forced to run one in Venice for the Fascists. From 1942 to 1968 he led a double life as a husband of Giuditta Rissone (and father of their daughter) and as a lover of Maria Mercader (and father of their two sons). He was also a gambler in more ways than one: not only did  he finance his best films himself when begging failed, but he was also known to bet several thousand dollars away one night after another at the tables of actual gambling establishments. He deplored Hollywood and yet he acted in studio films there and sought deals with some of the industry town’s biggest producers (Howard Hughes, for one, and David O. Selznick, who would have given him money for Bicycle Thieves if he’d been willing to cast Cary Grant in the lead). Oddly enough, De Sica’s most serious films were more successful in his day in the U.S. than they were in Italy at his home box office.

he finance his best films himself when begging failed, but he was also known to bet several thousand dollars away one night after another at the tables of actual gambling establishments. He deplored Hollywood and yet he acted in studio films there and sought deals with some of the industry town’s biggest producers (Howard Hughes, for one, and David O. Selznick, who would have given him money for Bicycle Thieves if he’d been willing to cast Cary Grant in the lead). Oddly enough, De Sica’s most serious films were more successful in his day in the U.S. than they were in Italy at his home box office.

Neorealism Today

In 2002 Bert Cardullo’s Vittorio De Sica: Director, Actor, Screenwriter was published, the first and only authored book on De Sica in English to come out in the United States. (There is also a remarkable anthology edited by Howard Curle and Stephen Snyder in 2000, and an invaluable double-disc DVD set by The Criterion Collection including three filmed documentaries on De Sica, Zavattini, and neorealism and a booklet of ten essays.) Cardullo offers a reprint of an interview with De Sica by Charles Thomas Samuels, in which the filmmaker explains why neorealism is not simply shooting films in authentic locales: “It is not reality. It is reality filtered through poetry, reality transfigured. It is not Zola, not naturalism, verism, things which are ugly…. (It) was born after a total loss of

authored book on De Sica in English to come out in the United States. (There is also a remarkable anthology edited by Howard Curle and Stephen Snyder in 2000, and an invaluable double-disc DVD set by The Criterion Collection including three filmed documentaries on De Sica, Zavattini, and neorealism and a booklet of ten essays.) Cardullo offers a reprint of an interview with De Sica by Charles Thomas Samuels, in which the filmmaker explains why neorealism is not simply shooting films in authentic locales: “It is not reality. It is reality filtered through poetry, reality transfigured. It is not Zola, not naturalism, verism, things which are ugly…. (It) was born after a total loss of  liberty, not only personal, but artistic and political. It was a means of rebelling against the stifling dictatorship that had humiliated Italy. When we lost the war, we discovered our ruined morality. The first film that placed a very tiny stone in the reconstruction of our former dignity was Shoeshine.”

liberty, not only personal, but artistic and political. It was a means of rebelling against the stifling dictatorship that had humiliated Italy. When we lost the war, we discovered our ruined morality. The first film that placed a very tiny stone in the reconstruction of our former dignity was Shoeshine.”

That film was made for $20,000. “It was the result of the war,” De Sica tells us, “whose first victims were those poor youngsters, ruined by Americans, money, the black market in cigarettes. And then we put them in prison!” De Sica had followed a particular pair of real shoeshine boys in the Via Veneto for a whole year, and even watched them ride a carousel at the Villa Borghese. After the theft of a gas mask, one of them ended up in prison. The filmmaker had published his story of shoeshine boys in a film journal he’d started after the war, and he’d taken photographs that he added to the article. A producer approached him the following year to make the film, but De Sica rejected the proposed writer and went to Zavattini, whom he’d met earlier in Milan.

Along with Bicycle Thieves and his earlier The Children Are Watching Us, De Sica and Zavattini set down the prototype for films upholding the point of view of children. Buñuel would follow with Los Olvidados, Truffaut with 400 Blows, Satyajit Ray with his Pather Panchali series, Gianni Amelio with Stolen Children (a clear homage to Bicycle Thieves), and Kiarostami with his own trilogy including Where Is the Friend’s House?. They’ve all become classics, and their authors and countless others have spoken of their debt to that melancholy poetry of Italian neorealism, a clarion to the moral investment in new generations.