Ask Julian Schnabel what drove him to make his current feature The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, based on the memoir by Jean-Dominique Bauby, and this is what he offers:

“I wanted this film to be a tool, like his book, a self-help device that can help you handle your own death. That’s why I did it.”

As explanations for movies go, this has to rank as one of the least sanguine in film history. A primer for the bitter end? Definitely not the kind of quote you’d stick on a movie marquis to drive up box office.

But then, who really cares about ticket sales when you’ve got a film like Schnabel’s that reaps rewards far beyond the domain of the mundane? This is a movie – or more precisely, a movable visual feast served on the canvas of celluloid – that’s alternately haunting, visceral, painterly, funny, outrageous, profoundly poetic and very likely to tease inspiration not only out of this world, but from the next as well.

beyond the domain of the mundane? This is a movie – or more precisely, a movable visual feast served on the canvas of celluloid – that’s alternately haunting, visceral, painterly, funny, outrageous, profoundly poetic and very likely to tease inspiration not only out of this world, but from the next as well.

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly is one of those movie projects that would seem hugely improbable in any universe, least of all one with creatures called investors and distributors. It’s based on the life and near death and subsequent artistic rebirth of Bauby, the roguish, high-flying editor of the French magazine Elle and father of two whose life changed instantaneously when, at age 43 and at the height of his success, he suffered a massive stroke. Weeks later he would awaken from a coma to the devastating news that he was totally paralyzed and forever “locked in,” a prisoner of his own body.

Jean-Do, as Bauby is nicknamed, likened his new reality to floating within the iron cage of a diving bell deep under the sea, under tremendous pressure and out of contact with the outside world. He was hopeless and helpless and spiritually dead. Until, that is, he found a way out of his trap, a means of releasing all the pent-up fury and disbelief to discover the raw wisdom and biting humor he had plumbed from the whole ordeal.

Jean-Do, as Bauby is nicknamed, likened his new reality to floating within the iron cage of a diving bell deep under the sea, under tremendous pressure and out of contact with the outside world. He was hopeless and helpless and spiritually dead. Until, that is, he found a way out of his trap, a means of releasing all the pent-up fury and disbelief to discover the raw wisdom and biting humor he had plumbed from the whole ordeal.

Bauby’s story became a worldwide bestseller when it was published in 1997, and ultimately inspired this third feature film from Schnabel, who previously directed Basquiat and the hauntingly beautiful Before Night Falls.

third feature film from Schnabel, who previously directed Basquiat and the hauntingly beautiful Before Night Falls.

The film was originally set up at Universal with Johnny Depp to star, but as Schnabel put it at a press junket recently, “I guess Johnny got busy with the pirate thing.” The whole concept of the movie then changed, from studio vehicle to a small, French-language project cast almost entirely with French name actors.

Chief among them are Mathieu Auric (Munich) who navigates fearlessly through the worlds of both the paralyzed Bauby of the present and the jet-setting rogue of his pre-stroke past; Emmanuelle Signer, last seen in La Vie en Rose and in her husband Roman Polanski’s Bitter Moon and Frantic, as his betrayed yet devoted (and stunningly beautiful) ex-wife; and the ever-watchable Marie-Josee Croze (The Barbarian Invasions) as a therapist who helps guide Jean-Do out of his “prison.” The biggest name of all is Max von Sydow, who plays the small but unforgettable role of Jean-Do’s aging father.

Each of these characters have a profound effect on Jean-Do in his altered state, moving in and out of the landscapes of his hospital room and his own memories that play like tiny movies in his head.

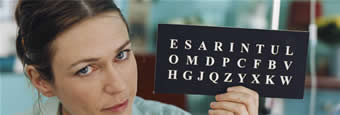

But the crux of The Diving Bell, and the part of the story that makes this film so compelling to watch, is in its portrayal of the almost impossible route Jean-Do takes out of his paralysis. Immobile and mute in his hospital room, and utterly devoid of self-pity, he finds new life by writing his own memoir using a painstakingly obsessive means of dictation. To form each word, he waits patiently while a clinic attendant reads the alphabet aloud, blinking with his left eye (the only movable part of his body) when the correct letter is reached.

But the crux of The Diving Bell, and the part of the story that makes this film so compelling to watch, is in its portrayal of the almost impossible route Jean-Do takes out of his paralysis. Immobile and mute in his hospital room, and utterly devoid of self-pity, he finds new life by writing his own memoir using a painstakingly obsessive means of dictation. To form each word, he waits patiently while a clinic attendant reads the alphabet aloud, blinking with his left eye (the only movable part of his body) when the correct letter is reached.

Through the act of writing, Jean-Do found a remarkable way out of his trap on the twin wings of imagination and memory – what he called “the point of view of the butterfly.”

During his 14 months of creating his manu scri pt in a hospital room by the sea, he’s able to transcend what had been a shallow but enormously successful life and make amends with his friends and family, to arrive at a place that was far more vibrant, essential and alive.

“Writing was the thing that saved Jean-Do,” explained Schnabel. “His interior life awakened. So I think the film is very much about the process of making art.”

Watching The Diving Bell is fascinating, because you see how the art of Schnabel’s film pays homage to Jean-Do’s. The movie is visually ravishing, saturated with images that move from shaky and out-of-focus to haunting and meditative (there are echoes of Bergman’s Cries and Whispers and Robe-Grillet’s Last Year at Marienbad here) to dizzying blasts of color and movement. Like Schnabel’s painting, the movie feels tactile and close to the skin.

Among Schnabel’s many innovations as director was to shoot the film entirely in French, even though the scri pt, by Oscar-winner Ron Harwood, was written in English so effectively it had been green lighted after the first draft. “I don’t think Ron Harwood liked it at all that I was going to translate his scri pt – and I translated it with the contributions and suggestions of all the different actors involved,” said Schnabel. “It had to come out of their mouths. But in the end everyone is happy with it in French. Even Ron Harwood.”

English so effectively it had been green lighted after the first draft. “I don’t think Ron Harwood liked it at all that I was going to translate his scri pt – and I translated it with the contributions and suggestions of all the different actors involved,” said Schnabel. “It had to come out of their mouths. But in the end everyone is happy with it in French. Even Ron Harwood.”

The French shoot meant the film would technically be considered a French film, although it’s not running as a French film for the Oscar’s foreign language film category. (The film Persepolis won that race.)

Perhaps the most surprising innovation is how Schnabel answered the one question that makes this movie seem, on paper, so damned improbable: How do you shoot a movie whose story is completely told through the eyes of a paralyzed, non-speaking narrator?

Schnabel’s response was to let those eyes – specifically, Jean-Do’s blinking left eye –become the camera for much of the movie. The first half of the film is shot entirely from Jean-Do’s point of view, allowing us to experience Jean-Do’s skewed universe exactly as he sees it.

Schnabel’s response was to let those eyes – specifically, Jean-Do’s blinking left eye –become the camera for much of the movie. The first half of the film is shot entirely from Jean-Do’s point of view, allowing us to experience Jean-Do’s skewed universe exactly as he sees it.

To simulate his distorted POV in the opening scene, when the disoriented Jean-Do wakes up from a coma after his stroke, cinematographer Janusz Kaminski and Schnabel built a strangely curved hospital ceiling and mounted fluorescent lights inside. The director even put his own glasses over the lens so that part of the image would be in focus, part out of focus.

And to film a poignant yet somewhat ghoulish scene when a doctor stitches up Jan-Do’s bad right eye, Schnabel simply put a piece of latex over the lens and sewed it up himself.

“The whole screen is like a skin and that’s how I see painting,” he continued. “It also makes you feel like you’re really seeing the movie from your own eyes, and makes you think about how we all see the act of seeing.”

Schnabel’s innovative use of Jean-Do’s POV also meant using a cinematic convention that’s generally shunned in movies, and which often fails when it is used: actors directly addressing the camera. “Normally that would stop a movie.in its tracks – it seems so odd at first, ” he conceded. “But pretty soon you forget they’re talking to the lens.”

actors directly addressing the camera. “Normally that would stop a movie.in its tracks – it seems so odd at first, ” he conceded. “But pretty soon you forget they’re talking to the lens.”

Certainly the actors didn’t. For Marie-Josee Croze, who plays his attendant Henriette, “it was very difficult being in the moment, because the camera gives you nothing. It’s cold. You have no response back. It was a very hard exercise.”

Yet somehow it all succeeds brilliantly. The cumulative effect of The Diving Bell’s innovations is to make you feel like you’re watching a feature-length experimental film, albeit one of the most emotionally layered and rich experimental films you’re ever likely to see.

“I just think necessity is the mother of invention,” Schnabel summed up. “Jean-Do needed to find a way to actually blink out his book, and ultimately, I needed to find a way to discover a form to tell his story.”

Coming up in the next BORDER CROSSINGS: Max von Sydow and Julian Schnabel talk about fathers, death, Ingmar Bergman and a director’s guide to self help.