Tucked away complacently in his Parisian home where, under the pseudonym “Eric Rohmer,” he is noted for spending years without a phone, a car, or even a taxi ride from time to time, but with family, faith, and a firm devotion to nature, cinema, and its related arts, Eric Rohmer might not mind that I muse over the paradoxes his life presents — to start, that he is by default one of the most enduring auteurs of the French New Wave despite his proclaimed distaste for the very auteurism that put the nouvelle vague on the map. His outpour of work has been ceaseless for 60 years, with predictably recurrent themes within a rigidly self-styled and vastly self-theorized brand of realism. And yet these austere and seemingly quotidian films swim free as fish in the waves of the Côte-d’Azur, well ahead of the lure that pulls fans back every time.

To catch the marvel of a Rohmer film in the moment is one thing, but to reduce it to words is possibly the one feat he would deny us, even if he himself wrote close to 300 articles, reviews, and books doing just that. Remember, this is the man who never allowed photos of himself on the set and drew up contracts to the effect that he would not be required to promote his films, who refuses festival appearances even at Cannes, and who donned a disguise of a moustache and glasses on the exceptional occasion that he arrived in Venice to be  lauded. In 2001 that city’s festival awarded him a “Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement,” which highlights the fact that no sizable film museum or cinématheque could withstand a periodic retrospective of his oeuvre.

lauded. In 2001 that city’s festival awarded him a “Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement,” which highlights the fact that no sizable film museum or cinématheque could withstand a periodic retrospective of his oeuvre.

Rohmer the realist has claimed over and over that art cannot improve upon life itself, and that the best cinema can do is to present life to us with as little interference as possible, to be a window on the world, to help us to see. It’s not difficult to accept this premise upon viewing his films as they charm us with the whims and wiles of the characters. What’s astonishing is to go behind the scenes for a minute and see exactly how it all transpired. Los Angeles affords such opportunities when its residents, many of whom are prestigious and long-time cinema artists, visit retrospectives like the recent eleven-film showcase of Eric Rohmer’s work at LACMA, to share their first-hand experiences, recollections and observations with audiences.

When Patrick Bauchau, a prolific international film and television actor over the last 30 years, was called to the stage on September 19th to converse with Ian Birney, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Film Program Director, a surprising déjà vu set in — in body and voice, mind and spirit. It was a balmy summer night. Bedecked from head to toe in white (collarless shirt, slacks, slip-on shoes, and vest), all that the actor needed was a straw hat to crown his casually dapper Saint-Tropez image. Elegant, astute, articulate, he was the prototypical Rohmerian cad and more. Bauchau is urbane and debonair (among other pursuits, his Belgian father and Russian mother ran a finishing school in Switzerland). If the actor’s physique and coloring suggest the figures of Gregory Peck and Sean Connery rolled into one, his lifestyle was perhaps closer to that of John Lennon. An Oxford graduate in Language Studies (he is fluent in five), Bauchau responded with graceful stage diction but also nuanced, hip English that anyone of Rohmer’s calling (the director had been a fiction writer and professor of French Literature) would have eaten up alive. By the end of the evening, it was difficult to decide who was more the enigma, Rohmer or Bauchau (who as the protagonist of the night’s film, the rarely screened La Collectionneuse, was an uncanny stand-in for the persona of the writer-director). To follow are excerpts from Bauchau’s responses; I conclude with my afterthoughts.

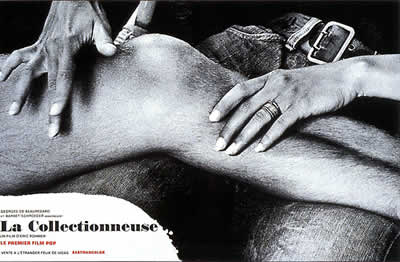

“Rohmer started with TV movies for schools — he had been teaching and then made these educational films — and gradually he went from Molière to his “Moral Tales.” He would do six variations on one theme, beginning with La Boulangère de Monceau and La Carrière de Suzanne, then to La Collectionneuse, and then to My Night with Maude, Claire’s Knee and Love in the Afternoon.

At that time I was in New York checking out what was happening in cinema. I wanted to be a part of it, maybe even direct, and it seemed there were two people who were really doing something fresh at the time — John Cassavetes, who had made Shadows, and Barbet Schroeder. They were unbelievable. When I returned to Paris I got to know the clan at Cahiers du Cinéma, the New Wave magazine Rohmer edited, through  Barbet, who was acting in Rohmer’s first “Moral Tale” and then producing Rohmer’s films through his own company, Les Films du Losange. So I got a role in the second “Moral Tale,” and then again in the third one to be shot, La Collectionneuse.

Barbet, who was acting in Rohmer’s first “Moral Tale” and then producing Rohmer’s films through his own company, Les Films du Losange. So I got a role in the second “Moral Tale,” and then again in the third one to be shot, La Collectionneuse.

We used to meet at the home of Madame Schroeder, Barbet’s mother, and Rohmer got us to talk about our lives. We talked into his Nagra and Rohmer recorded us; this was the basis for his screenplays.

The dialogue for La Collectionneuse is overwritten. In French you hear that it has an 18th-century flavor to it. Rohmer sees the 18th century as the apex of civilization. He likes the quality of the language at that time (for example, in La Marquise d’O…). So Adrien, my character in La Collectionneuse, read Rousseau.

There never really was a script. In the mornings Rohmer would give us a page of dialogue, which was what he thought was our take on the scene. We then improvised, which is a big word, because we had no chance for mistakes or experiments. We had two hours of film stock, so we had a single take to get it right — or not at all.

It was Nestor Almendros’ first feature, so he used mostly natural light. We shot from 6 a.m. to 9 a.m., keeping the same hours as the characters in the story, and then again at 4 p.m. to be able to use the same quality of light. We had no electricity. No sound track was shot. It was all dubbed.

This was my first dash at acting — Rohmer just threw it at me. It’s a real ‘60s piece — it was a shocker when it came out. Every critic in France hated it. They tossed us off as a bunch of hippies. Yet a guy found a 60-seat theater in Paris and kept it running for three years . No one made a nickel from this movie (except maybe Barbet).

. No one made a nickel from this movie (except maybe Barbet).

In the film, Haydée is totally mysterious… What became of her? The last scene ends with us on the road, and she’s invited into another car when friends pass by. She goes off with them to Italy — as she did in life. La Collectionneuse ended in Saint-Tropez. Just then the actress (Haydée Politoff) went to Italy and became a movie star for ten years and then married a British rock star and moved to San Francisco and may be living in America now, somewhere around Big Sur.

Carole, the girl who ran off to London at the beginning of the film, is my wife, Mijanou, and it was her last role.

There’s a Proustian feeling to Rohmer’s films. His fascination with tapestries and sculptures, for example, shows him to be an ancien régime, not a nouvelle régime, figure. There is a monarchist aspect to his personality. He keeps a very private life. No photos have been taken of him in the 40 years since he started his company with Barbet. Maurice Scherer is his real name. We see him at tea time, Barbet and I and others — you can visit him then — and he is surrounded by girls, and they talk, and talk, and he gets it all down….”

Looking at Patrick Bauchau on LACMA’s stage, I reflected on Rohmer’s breakthrough as a filmmaker. When La Collectionneuse won a Silver Bear at the 1967 Berlin Film Festival, outside of showcasing Rohmer’s own personal brand of realism, it launched his appeal for filmgoers across Europe. The 35 mm film, shot in luminous Eastman Kodak color stock and with a shooting ratio of 1.5 to 1, established Nestor Almendros as an innovator of naturalistic cinematography. The tiny coterie of crew and cast (who lent their real-life personalities to their characters via Rohmer’s incorporation of snatches of their recorded conversations into his original script with their shared writers’ credits) had lived together in one villa at Ramatuelle near Saint-Tropez to make the film, which cost $12,000. The first run of La Collectionneuse in Paris brought 50,000 viewers to see it (most of them at the Left Bank art cinema, Studio-Gît-le-Coeur) with 300,000 tickets sold in all runs.

Looking at Patrick Bauchau on LACMA’s stage, I reflected on Rohmer’s breakthrough as a filmmaker. When La Collectionneuse won a Silver Bear at the 1967 Berlin Film Festival, outside of showcasing Rohmer’s own personal brand of realism, it launched his appeal for filmgoers across Europe. The 35 mm film, shot in luminous Eastman Kodak color stock and with a shooting ratio of 1.5 to 1, established Nestor Almendros as an innovator of naturalistic cinematography. The tiny coterie of crew and cast (who lent their real-life personalities to their characters via Rohmer’s incorporation of snatches of their recorded conversations into his original script with their shared writers’ credits) had lived together in one villa at Ramatuelle near Saint-Tropez to make the film, which cost $12,000. The first run of La Collectionneuse in Paris brought 50,000 viewers to see it (most of them at the Left Bank art cinema, Studio-Gît-le-Coeur) with 300,000 tickets sold in all runs.

LACMA’s eleven-film retrospective of the master, who is now 87, spanned the “Moral Tales,” the “Comedies and Proverbs,” and the “Tales of the Seasons,” following Rohmer’s intimately aligned and maligned characters to the beach or the vineyard or the pied-à-terre, from the Riviera to Normandy or to Paris under the full moon, where cerebral but spontaneous, they ponder and amble and crisscross each other with the directionless precision of a well-made play. They talk and think out loud (via a narrator) and talk some more. It’s Marivaux at Le Mans or Molière at Annecy, but in jeans and bikinis. Self-absorbed, and mildly and unconsciously obsessed, Rohmer’s casualties of jeux d’amour pull themselves “together” despite the value of the risks they might have taken.

My thanks to Mijanou and Patrick Bauchau and to Ian Birney for an informative evening and a delightful series — Diane Sippl