CLUJ, Romania — One of Europe’s most innovative and newly-heralded filmmaking communities is Romania’s New Wave, which last summer was put in sharp focus at the country’s leading film forum, the Transylvania International Film Festival. CWB’s International Editor James Ulmer visited the Festival in June and spoke with its trio of lead executives about a variety of topics, from life after communism and the festival’s political birth pangs, to why drive-ins are Romania’s next Big Thing. Present were Honorary President Tudor Giurgiu; Festival Director Mihai Chirilov, who founded the festival in 2001 with Giurgiu; and Executive Director Rik Vermuelen.

James: Some people might argue that Romanian cinema and the festival itself have had a kind of arrested development. There was a new political renaissance after 1989 when the Ceausescu regime fell. Yet it still took another – what, 13 years? – for Romanian films to catch up and have their own renaissance, and for you to come up with a festival. Why so long?

Rik: Well, there needed to be some distance. Some of our best filmmakers now were teenagers when the revolution broke out and Ceausescu was dismissed. They’d seen one side of the period and they had the opportunity to process what had happened and to distance  themselves from the generations before them. They managed to find answers, and that takes time.

themselves from the generations before them. They managed to find answers, and that takes time.

Mihai: Before ‘89, Romanian filmmakers were very good at making propaganda movies. We were very good at making silly comedies. We were very good at making adaptations and costume dramas. We were good at this type of filmmaking because (these films) were all politically safe. Back then, we used to have one of the biggest studios in Europe. And we had communist state money sponsoring the cinema, because in a very crazy way they were smart enough to use cinema as a propaganda weapon. Today, the state and the authorities are not smart enough to use the new Romanian film successes in promoting Romania.

After ‘89, our filmmakers were free to do whatever they wanted. And all of a sudden we realized that our great filmmakers were actually not that great. The films right after 1989 were very aggressive and angry. It took some years before they became more legitimate and maybe more powerful, because their view was not so infected with revenge, with hatred. It became true political cinema because it made a political statement that was valid and true. It had been seasoned.

Rik: Yes, exactly.

Tudor: And there’s a big difference about what happened in Romania compared to other countries. For example, we here in Romania (especially this generation) aren’t doing the kind of movies you might see in Hungary and the Czech Republic —that is, films in a very sophisticated cinematic language with a lot of metaphors. I think this type of cinema is perceived by my colleagues as part of the past. Now everybody’s trying to find a very direct expression.

James: Mihai, from a filmmaking point of view, what does the so-called “Romanian Renaissance” in cinema mean to you?

James: Mihai, from a filmmaking point of view, what does the so-called “Romanian Renaissance” in cinema mean to you?

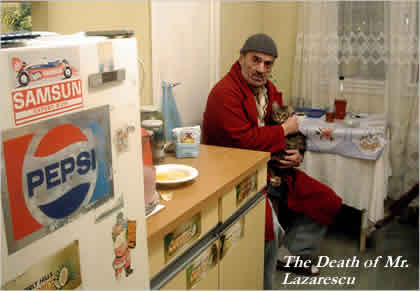

Mihai: Well, in the black year of 2000, no Romanian films were made. None! So everybody was depressed. Then all of a sudden in 2001 a guy called Cristi Puiu [who later made the acclaimed The Death of Mr. Lazarescu] came up with a small film, totally different from what we were trained to acknowledge in our cinema here. The film was called Stuff and Dough. It received acclaim at Cannes and afterwards it was shown in Bucharest and created a big scandal, because the movie used handheld cameras and the photography was very rough, not to mention the language. So everybody was shocked. Then Christian Mangiu [who later made 4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days] called me and said he had his first feature, Occident, and we saw it and instantly decided to open our festival with it – with a Romanian film! We took a risk, and eventually the film was successful. So starting in 2001, the new Romanian cinema’s history really mirrors our film festival’s history.

James: I noticed this festival is filled with kids in their early 20s. Is that just because this is a university town?

Tudor: Well, it’s also because Cluj has the biggest cinema attendance per inhabitant in Romania. It’s double that of Bucharest. People really do love cinema here.

James: So you’ve got great attendance. But to make a truly international festival you need at least two things — international premieres and stars. And stars charge money to attend. The Moscow festival once paid literally hundreds of thousands of dollars for Jack Nicholson to attend, and Catherine Deneuve, who’s a guest of your festival this year, reportedly charges at least $30,000 if not more. How can you afford that kind of money? And do you have to play that game?

Tudor: Stars, okay, are important for media and press. But they do not always charge money to make an appearance…We’ve managed to develop certain relationships with both stars and filmmakers in various countries…Vanessa Redgrave didn’t charge anything when she came here.

James: She usually needs a social cause to lure her to a festival.

Rik and Mihai: And she found it!

Tudor: Yes, some years ago it was still a big issue here about the exploitation of workers in the gold mines owned by a big corporation. We had a bit of a delicate situation because this corporation was one of our sponsors. Vanessa wanted to fight for the people being  oppressed by the corporation and the big capitalists. It was okay with me but Mihai was a bit angry.

oppressed by the corporation and the big capitalists. It was okay with me but Mihai was a bit angry.

Mihai: I was very angry because you know, we were inviting her to a film festival, not to a political session. We were paying for her trip and hotel and promoting her films and screening a film of her choice – which by the way the audience here totally hated. I didn’t want to meet her at all, so I managed not to meet her during the whole festival. Not at all. Not even a handshake.

Tudor: I’m the diplomat and he’s the impulsive one.

James: So you used Vanessa Redgrave’s name to bring in audiences and you don’t go meet her? Fair or not?

Mihai: How could I meet someone whose very first words she said when she landed – after she’d found out about the gold mines and the worker exploitation – was ‘Who are these criminals? They should be called criminals! I want to talk to the directors of the festival!’ Well, I don’t want to talk to someone who’s thinking that I’m a criminal. Come on! Give me a break. You don’t even know me and you’re already judging me. Why? Bullshit.

James: Rik, people here have told me that the Romanians themselves aren’t going to movies as much as they used to. They’re watching DVDs at home. They can’t smoke in the cinemas – everyone seems to smoke in Romania – so they do their movie-going in the freedom of their living rooms.

Rik: I think we’ve found the answer to that problem: Cinema-going here has to become an experience. We have two open-air cinemas where you can smoke and drink, and for the first time we have a drive-in this year. We had hundreds of cars come to our first drive-in last Friday. It was a very big mall with an outside parking lot on the roof, so we decided to put a screen on the top of one parking lot, along with a great sound system. And we opened with the Rolling Stones’ Shine a Light and each night was full with three or four hundred people. We have to now reconsider the films for this, because we have a lot of teenage audiences and couples.

James: They were too busy being entertained by themselves? (Laughter)

James: They were too busy being entertained by themselves? (Laughter)

Rik: Whatever. It was fantastic.

Mihai: You just have to adapt to what the market wants. Romania is not such a rich country, but the latest brands of cars are here long before they are in France or anywhere else – even Rolls Royces. Considering the poor quality of the streets, it says something about the nouveau rich. The car, for most Romanians, becomes something of a comfortable second skin. So the drive-in has become something very cool to them, and the experience was brand new, totally revolutionary. They were watching. They were eating. They were having sex. Just like at home. Because in a cinema you cannot smoke, you can hardly eat, and forget about sex.

James: Tell me your festival’s biggest success and your biggest disappointment in the last seven years.

Mihai: The biggest success I think was last year because it was one of the great years of Romanian cinema. The other side – the not happy side – is that it takes time for the audience to understand that they shouldn’t be so aggressive and so negative and so limited about some films – like Michael Haneke’s Funny Games US — just because they’re dealing with themes and ideas which are not so comfortable to them…Most American cinema promotes the idea that life makes sense. That nothing can be absurd. That eventually someone will come to save the day. And that we’ll all be winners. But life is not that simple, and you can be easily fucked up if you think that narrow-mindedly.

James: Do you suppose, Mihai that American audiences think Obama will come in and save the day for us?

Mihai: (Laughs) I don’t know. Should I care?