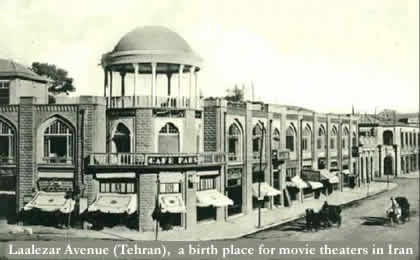

Cinema came to Iran courtesy of Mozafaredin Shah, a king of Iran who visited Paris around the turn of the century, fell in love with the Can-Can and the magic of the cinema; he fooled around with the ladies and bought himself a brand new motion picture camera.

Accompanying the King was one Ibrahim Khan, part noble, part peasant. He learned to use the camera and then shot the first Iranian movie. No one ever recorded his name in any film history, but he was the first to use panoramic movement in his documentary of the King’s harem and his 250 wives.

Love for the movies spread very fast from the royal palace to the narrow, stony streets of Tehran. Traditional and conservative people quickly perceived and condemned films as immoral. Rumors started to go around describing movies as a path to prostitution, a dangerous drug and a creation of Satan. According to these rumors, a monstrous, hungry dragon awaited all movie lovers in hell. Its thousands of eyes each projected a different movie scene, then turning to flames, they would burn the film fans (My uncle used to say: “What a hot retrospective!”).

Kids all loved to imitate Chaplain and Valentino in the school yards and streets of their neighborhood. When the lights were extinguished for Friday night prayers in the mosques, children hailed each other with Tarzan’s piercing jungle vibrato.

Shah’s regime imposed a heavy censorship over the movies with any social or political theme. As a result, the 60 to 80 features produced each year, all shared the same melodramatic concept, and a poor guy falls in love with a girl from a wealthy, high class family. First he loses her to a rich playboy but eventually wins her back and takes her hand in marriage.

The government welcomed these movies since they encouraged false hopes and dreams among the poor masses. In these movies rich men were portrayed as fat and bald. Sexy women, dressing either in an evening dress or pink, silk nightgowns, were always descending or climbing marble staircases under huge chandeliers. One of these naive filmmakers once shot a party scene inside an empty swimming pool, and called it the pool party!

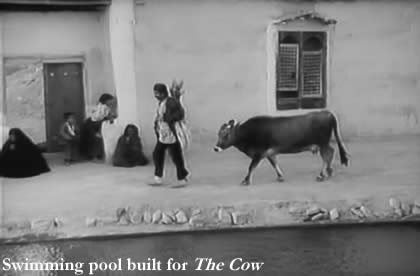

In children’s movie, the act of jumping over a fence was forbidden, as it was widely regarded as a symbol of rebellion. Including a rose in the frame was avoided since a popular poet of the leftist opposition had  been executed by Savak- the Shah’s secret police. His name Gollesorkhi, means rose . An unemployed character in a movie was employed with a good salary in re-edited version. In the movie “The Cow“, a big swimming pool was build in the middle of a half ruined village to show the progress of the country, which for the director was the only way to screen his brilliant movie carrying a social and political message.

been executed by Savak- the Shah’s secret police. His name Gollesorkhi, means rose . An unemployed character in a movie was employed with a good salary in re-edited version. In the movie “The Cow“, a big swimming pool was build in the middle of a half ruined village to show the progress of the country, which for the director was the only way to screen his brilliant movie carrying a social and political message.

An unwritten but widely adhered rule of Iranian cinema was that all police officers should be portrayed as sweet and kind, but more importantly, as winners. No wonder that in the final reel, cops pop up out of nowhere to catch the nasty bandits.

When “Madame X” played the theaters, tickets were sold along with small boxes of tissues. But audiences were crying so hard that just one box of tissue was not enough. We all loved crying those days. We had cried so much on the anniversary of the death of our saints that we enjoyed crying. That is why Indian films were extremely popular in Iran.

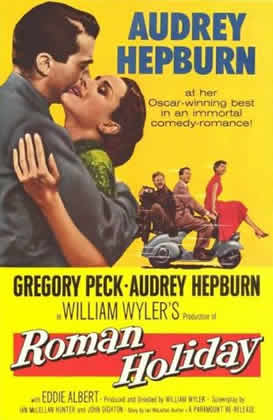

But what personally broke my heart was Audrey Hepburn choosing Gregory Peck over poor Edie Albert in “Roman Holiday”. After that, I tried to look like Gregory Peck, but the more I tried, the  more I become a copy of Edie Albert.

more I become a copy of Edie Albert.

Broken hearted, I decided to seek revenge by becoming notorious. I wrote an expose of rude behavior among audience members at the cinema and submitted it to a film journal. It focused on a particularly annoying phenomenon. At that time there were people who, after seeing a show, would pass the long line of people waiting to get into the next show and reveal the end of the movie to them. What made this all odd sight, from a distance, were all the ticket holders clasping their hands to their ears to safeguard their entertainment investment.

I considered it a great milestone in the history of arts and letters when I discovered my article had been published. That same evening, feeling flushed with self importance, I showed the magazine all around to my friends and co-workers, none of whom could read or write. Still, they seemed impressed and said they loved it.

Bitten by the bug now, I wrote and submitted a second article. In it I analyzed the underlying meaning of different color schemes that were prominent in one of Vincent Minelli’s films. It was a minor tragedy when I discovered that the copy I had seen had been a bad one and that all the colors in it had shifted radically.

At the age of 18, through friends at the film magazine, I landed a job teaching classes at an evening school located downtown. As I had no teacher’s license, the school master appointed me to a special class for which he had been unable to find the right teacher. Actually, it was the one class no teacher had been willing to take on.

The course was Elementary Education. The pupils were referred to as “PP”. It was, to say the least, not an ordinary class. My students were, to a man-and a woman: pimps and prostitutes!

Terrible nightmares woke me In the middle of the night as I worried myself silly over what might happen in those classes. After all, those people had come to regard murder and mayhem as a sort of hobby. Again the wonderful world of film came to my rescue. I knew for a fact that these folks, even more than ordinary people, regarded movies as a kind of escape hatch into a dreamland they otherwise could never know. No matter how farfetched the  idea, whatever the lesson of the evening concerned, I worked it into a discussion of a particular movie.

idea, whatever the lesson of the evening concerned, I worked it into a discussion of a particular movie.

Eventually, I presented to the class, my audience, a Farsi version of “Seven Brides For Seven Brothers“. Using the lectern as a camera, I directed the students to act out the play as though it were being filmed. I was, of course, the director. Songs and dances were from our native folklore traditions. Each of the students was instructed to write down his or her parts. In this way I got them started learning how to read and write! It was not surprising that a few of the ladies actually wanted to marry me.

I was a customer of Mashdi, visiting his shop for a hair cut once in a month. It was there that I met Hameed, Mashdi’s only son. Hameed was in his early twenties and invited me to work at his small sound studio. I began work cleaning Hamid’s motion picture sound studio. Here I discovered the extraordinary world of sound effects. Hamid ran the place, and on blistering hot summer days he would delight in filling the studio with the sound of arctic winds and cascading waterfalls.

Our job was not limited to dubbing and mixing the sounds, but included the dubious task of making them “acceptable” to the authorities. This was especially the case with foreign imports, such as an American film, “The Collectioner“. We had to add the sound of a police siren over the closing shot so that the audience would assume the bad guy would be captured. Looking back now, I can clearly remember how, from the time they were first introduced, movies always struggled with the powers that ruled Iran.

remember how, from the time they were first introduced, movies always struggled with the powers that ruled Iran.

Sometime after this I had my first chance to work on a feature film as a cameraman. A friend of mine, in his late twenties Amir had worked since childhood with his twin brothers. They did an acrobatic act in which they formed a human pyramid. He, being the youngest, was the man on top. He became suddenly unemployed, though, when a tragic auto accident cut short the lives of his brothers. At least that was his version of story.

Amir had decided to make a feature film. His strategy was something completely new. Instead of paying the actors to work for him, he managed to convince them to pay him! He targeted those desperate souls who haunted the entranceways to studios, eager to get even the smallest walk-on parts in a movie. Amir’s genius was to offer them the leading roles.

We began by scavenging the studios for leftover negative. But our main problem was the absence of any movie camera. Amir found a solution to this dilemma through a friend who worked at the Ministry of Information. This fellow managed to spirit away from a museum a vintage World War I camera that still operated. The entire film was shot on this trusty antique. When the movie was finished, we took the entire negative to the lab. That same day, which also was my 18th birthday, the secret police raided the lab, a routine check to find suspicious materials against the government.

Unfortunately, the officer who wanted to check our project decided to have a look at the unprocessed negative in the bright sunlight. Later that evening, after crying with Amir over the lose of our masterpiece, I wrote a poem. Here is the part I remember:

I turned eighteen and my baby died,

Like Shane, he left for a lonely ride.

The brutal, ignorant, nasty police,

Aborted my wonderful masterpiece

*“I Remember Cinema is written based on collective memories of my friends and myself, mixed with dreams, fantasies, facts and history.”