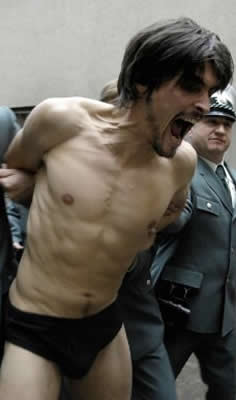

The Baader Meinhof Complex happens in Germany in the 1970s: Murderous bomb attacks, the threat of terrorism and the fear of the enemy inside are rocking the very foundations of the yet fragile German democracy. The radicalised children of the Nazi generation lead by Andreas Baader, Ulrike Meinhof and Gudrun Ensslin are fighting a violent war against what they perceive as the new face of fascism: American imperialism supported by the German establishment, many of whom have a Nazi past. Their aim is to create a more human society but by employing inhuman means they not only spread terror and bloodshed, they also lose their own humanity. The man who understands them is also their hunter: the head of the German police force Horst Herold. And while he succeeds in his relentless pursuit of the young terrorists, he knows he’s only dealing with the tip of the iceberg.

The Baader Meinhof Complex happens in Germany in the 1970s: Murderous bomb attacks, the threat of terrorism and the fear of the enemy inside are rocking the very foundations of the yet fragile German democracy. The radicalised children of the Nazi generation lead by Andreas Baader, Ulrike Meinhof and Gudrun Ensslin are fighting a violent war against what they perceive as the new face of fascism: American imperialism supported by the German establishment, many of whom have a Nazi past. Their aim is to create a more human society but by employing inhuman means they not only spread terror and bloodshed, they also lose their own humanity. The man who understands them is also their hunter: the head of the German police force Horst Herold. And while he succeeds in his relentless pursuit of the young terrorists, he knows he’s only dealing with the tip of the iceberg.

Uli Edel, director of The Baader Meinhof Complex, studied German literature and drama at Munich University before enrolling at the Munich Film Academy. Here he directed his first short films, which were produced by his fellow student and friend Bernd Eichinger.

In 1981, Uli Edel, once again with Bernd Eichinger as producer, directed CHRISTIANE F.. The film was a worldwide success and won numerous international awards (including the Montreal Film Festival).

In 1989 in New York, Edel and Eichinger made their next film together, LAST EXIT TO BROOKLYN (starring Jennifer Jason Leigh and Burt Young), based on the novel by Hubert Selby. The film  won the German Film Awards for Best Film and Best Director and the Bavarian Film Award in 1990. In the USA it won the New York Film Critic Award and the Chicago Film Critic Award, amongst others.

won the German Film Awards for Best Film and Best Director and the Bavarian Film Award in 1990. In the USA it won the New York Film Critic Award and the Chicago Film Critic Award, amongst others.

Uli Edel has been living in Los Angeles since 1990, where he’s made a successful career as a director of event movies and miniseries for US pay TV, winning numerous awards. To name but a few, his TV movie “Rasputin” won 3 Golden Globes and 3 Emmies. “The Mists of Avalon” was nominated for 11 Emmies and was voted Best TV Film at the 2001 San Francisco International Film Festival. His western, “Purgatory”, made television history: it became the most successful cable TV movie in the history of US television, with 31 million viewers on its first showing.

Bijan Tehrani: How accurate is The Baader Meinhof Complex to the true events? Did you try to make it as accurate as possible?

Uli Edel: Yes, I tried to make it as accurate as I was able to. You try to search for the truth. A lot of people these days in Germany remember what happened. Everybody knows a little bit of it, remembers the fighting in the streets, the death of Benno Ohnesorg, the police beatings. I wanted the audience to experience the feelings I had, when these things really happened 30, 40 years ago. Many of these moments are also iconic images that are part of my generation’s consciousness. Like those images from the 60’s in America, the student girl over the body at Kent State or the people pointing from the balcony when Martin Luther King was shot. They are etched in the American collective memory…it’s visual shorthand which elicits an immediate gut memory.

But you can only get so close to the truth; at one point a movie always develops its own reality. The choices you make as to what to show is already bending the truth. It becomes very subjective. I don’t believe that there is something out there like “The Truth”.

BT: There are always many versions of the truth.

UE: Yea, exactly. What I chose is what I wanted to communicate to the audience. On the one hand, I always look for a key when I start a project. There are many ways that you can do it, and what you tell and eliminate can vary. Here the key for me was to tell this story to my sons. They are 20 and 21 years old now. They grew up in America, and did not know anything about the Baader Meinhof group. They did not know what happened in 1968 in  Europe, and they are now the age that I was when it all started. I was 20 years old when Benno Ohnesorg was shot, and on my 21th birthday when Rudi Dutschke, who I admired as a young student, was almost killed in the streets of Berlin. These are the moments that you can compare here in the US with Martin Luther King Jr. being shot, or Robert Kennedy 6 weeks later. The man who shot Dutschke got the idea because the MLK shooting happened 7 days earlier. It was clear for me how I had to tell the story to my sons. They are American, but I knew exactly what to tell them.

Europe, and they are now the age that I was when it all started. I was 20 years old when Benno Ohnesorg was shot, and on my 21th birthday when Rudi Dutschke, who I admired as a young student, was almost killed in the streets of Berlin. These are the moments that you can compare here in the US with Martin Luther King Jr. being shot, or Robert Kennedy 6 weeks later. The man who shot Dutschke got the idea because the MLK shooting happened 7 days earlier. It was clear for me how I had to tell the story to my sons. They are American, but I knew exactly what to tell them.

BT: What kind of judgment do young people make when seeing this film? For them, what happened probably sounds too crazy.

UE: That’s the point. When they saw it the first time, their reaction was, ‘is this really true?’ They could not believe it, they really couldn’t.

BT: And they cannot understand that people like that existed.

UE: They understood quite well after seeing the movie why it happened, why some students were so radicalized. In Germany it was quite different from other western countries. This generation, the post war generation, were the children of the parents who brought Hitler to power. We grew up carrying the shame of what happened. We didn’t forgive our parents, that they didn’t prevent it, that they didn’t resist. These young students said, we cannot allow this government to become a fascist government again. Our generation had to resist, and we strongly believed that if we didn’t, it will happen again. 1968 we still had a chancellor who was a former Nazi. We did not trust the government, did not even trust our own parents.

BT: The whole world is so different now. In Iran, we used to think that the German intellectual movement is very active. We used to say that the French think about it, but the Germans do it. The two main characters, Ulrike and Andreas, are so believable. You don’t doubt them at any moment. Did you do a lot of research on those two characters?

UE: Yes, I did a lot of research. As a student I read, almost religiously, everything that Ulrike wrote. Even if I didn’t under it stand. She was a very important and influential figure at that time. Everybody knew her. Baader was different. He was never really an established guy. The way he talked, he tried to be very anti-intellectual, he treated women almost like a pimp did, also the way he talked. But he had something very charismatic about him. He became a kind of rock star after the trial in Frankfurt. There was even a movie in 1969 about him. In contrast to Ulrike Meinhof he was never really established, before he became an outlaw. For Ulrike, it was a huge step to jump through that window and follow him. She had to leave a whole world behind her; a family, two children, her reputation. It happened almost casually. She did not know that she was going to jump through that window that day. Some people argue that she planned on doing it, but that is not true. She might have thought about it already, but she had not planned to do it that moment. It was a stupid thing to do, and there was no return. If you can identify with somebody, it is with her, but only for a little while. There is no way to understand her when she puts these bombs in that publishing house. I remember very well what I felt when it happened. I tried to recreate in the movie what I felt back then: what the hell is she doing? Did she loose her mind completely?

You couldn’t identify with her anymore at that point.

Later in prison they gang up against her and she becomes a truly tragic figure; it is just a logical development in such an isolated environment, that they start to torture each other until complete self destruction.

BT: I think this was even something going on in Iran with those working towards a more peaceful movement, but ended up turning into an armed movement. If you are going to use the same tactics like your enemy, you will turn into your enemy. What has the reaction of the German audience been so far?

UE: It was a huge success in the theaters. But the discussions have been very controversial. There are a lot of people in Germany who don’t want to remember that time at all. The most controversial thing of the movie definitely is that the most famous german actors play terrorists, that the girls are so beautiful etc. But the facts are: 60% of the members of the group were women; smart, intelligent, and mostly quite attractive women. As a director, why would I hire worse actors when I could have the best actors? For me it was also very important that I knew these characters. They were not just the typical bad guys. These people were in University with me, sitting perhaps in the same class with me, demonstrated in the streets with me. They could have been my friends, before they started to kill people in the name of a political idea.

The scene when one of the guys dies from a hunger strike, well, he was a film student in Berlin, while I was a film student in Munich. He was a friend of the director Wolfgang Petersen and cinematographer Michael Ballhaus. These are not just bad guys, they came from inside our society, from our surroundings. It is very important to know that. That is also why I empathize with Holger Meins when he is lying on that gurney, dying. You can’t help but feel compassion for him even not knowing the guy.

The scene when one of the guys dies from a hunger strike, well, he was a film student in Berlin, while I was a film student in Munich. He was a friend of the director Wolfgang Petersen and cinematographer Michael Ballhaus. These are not just bad guys, they came from inside our society, from our surroundings. It is very important to know that. That is also why I empathize with Holger Meins when he is lying on that gurney, dying. You can’t help but feel compassion for him even not knowing the guy.

BT: I think it is important for the young people in the United States to see this movie. They are always shown an image of terrorists as crazy people who are not from this planet, without understanding the reasons that make people turn to terrorism.

UE: Exactly. I try to make it clear in the movie that when the bombing and shooting starts, what they did was cold hearted murder. The second generation really had not even a political goal anymore, only to get their leaders out of the prison. And to achieve that they created a blood bath, and there is no excuse for that.

BT: The part of the film shot in Jordan was very interesting. Did you have any documents to base that part off of?

UE: I based it off the narration of two people who were there. I based it on the friend of Ulrike, who followed her to the camp. I interviewed him in length. And Peter was a close friend of Stefan Aust, who wrote the book. Stefen Aust was the young boy who gets the children back from Sicily. He also knew Ulrike very well, and after Peter returned from Jordan, he and Stefan lived together as students in Hamburg. So Stefan Aust also was a very important source for that scene. Also the other member of the group I interviewed is the woman with black hair, who screams throughout the prison for Ulrike. She was also trained by the PLO in that camp. Today she lives in Berlin as a teacher. I met with her too. I interviewed six members of the group at length. They are all out of prison by now.

BT: Where are you going from here? What will your next project be?

UE: Hopefully I can do another political subject. But it will not be the next movie. The next one is based on a German book, set ten years after the war. It is about a young man who falls in love with his teacher. No guns, no bombs, just from the heart