Agust 2013 – Like comfortable old shoes, favorite films are meant to be lived in. Some evenings I’ll shuffle about my DVD collection and slip into a well-worn movie for the sheer, toe-squishing pleasure of revisiting old friends and haunts. These companions never seem to wear thin, even when I myself am feeling worn out.

As an itinerant film journalist, I’ve sometimes reconnected with my favorite movies by crossing borders and oceans to visit the places where they were filmed.

The most memorable locations are those tiny, idyllic villages that make me want to trade L.A.’s hyper-connected and stressed-out rhythms for a simpler, saner commute to the other side of the screen. Usually these villages are in Europe, and most often in my favorite country, Italy. They’re villages like those impossibly charismatic ones in Cinema Paradiso, Il Postino, The Star Maker and The Godfather trilogy. For me, these films are so well-worn they practically have holes in them.

Call me a shameless romantic, but last spring I splurged on a discount flight to check out my favorite film village, one that’s often overlooked by the legions of tourists descending upon Italy. Within moments of arriving in this sleepy little Shangri-la I was hooked on the pleasures of cinematic deja vu: re-visiting in real life the locations I’d fallen in love with in reel life. (More about this in a moment.)

Call me a shameless romantic, but last spring I splurged on a discount flight to check out my favorite film village, one that’s often overlooked by the legions of tourists descending upon Italy. Within moments of arriving in this sleepy little Shangri-la I was hooked on the pleasures of cinematic deja vu: re-visiting in real life the locations I’d fallen in love with in reel life. (More about this in a moment.)

There’s actually a method to this mad extravagance, and it’s worth sharing with the daring among you who may someday want to shuffle off to the lands of your own celluloid dreams.

1. Identify which of your favorite films feature fabulous film villages.

Ask yourself: In which films could I happily imagine falling in love, or at least renting a romantic run-down villa for the summer? For me, the delightful Czech town of Ivan Passer’s Closely Watched Trains could qualify, or the sleepy French village in Manon of the Spring, to name but two.

But for sheer village bliss, I’d have to choose a room with a view onto an Italian piazza. Especially a piazza in a film by Fellini – or by Visconti or Pasolini or Rossellini or Bertolucci or Tornatore or the Taviani brothers. You get the picture.

Whatever your choice, don’t hesitate to pander to your most romantic and nostalgic urges. If, while watching these movies, you don’t ache to leap from your chair and inhabit one of these film villages at least until the end-credits (if not until the end of your days), abandon this exercise entirely.

2. Make your peace with the piazzas.

The piazzas are the nexus and nerve center of village life, the places where all roads of the film’s story converge. In the village piazzas you meet all those classic characters of Italian cinema. There’s the love-struck Romeo, the prankster school kid, the pompous padrone and  the honey-hearted prostitute who keeps their secrets. You might even meet the village lunatic who doubles as a philosopher. Or the “family” Don who doubles as a lunatic. The piazzas connect them all.

the honey-hearted prostitute who keeps their secrets. You might even meet the village lunatic who doubles as a philosopher. Or the “family” Don who doubles as a lunatic. The piazzas connect them all.

As a boy in Naples I remember running into whole casts of these characters at the weekend fish markets, so the piazzas connect me to my own past, too.

Once you’ve familiarized yourself with the piazzas in the villages of your favorite films, skip to the DVDs’ end credits and jot down the list of names of their filming locations. Get familiar with the pause button; you’ll need it.

3. For best results, set your sights on Sicily.

Any hunt for the world’s finest film villages should begin and end with Homer’s isle. Set next to Italy’s boot like a drop-kicked football, Sicily boasts a magical mix of mythology and history unlike any other island on earth. Remember Ulysses’ fantastic voyage in The Odyssey? Almost all of it played out in Sicily. Plopped in the middle of the Mediterranean’s ancient trade routes, Sicily is also the crossroads for countless real-life conquerors,  from the Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans to the Vandals, Arabs, Normans and French. Whatever they sought has long been won and lost, but happily, you can still find their marks everywhere on this age-old stage.

from the Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans to the Vandals, Arabs, Normans and French. Whatever they sought has long been won and lost, but happily, you can still find their marks everywhere on this age-old stage.

With such an exotic cast of characters, is it any wonder the island harbors some of the world’s great film locations?

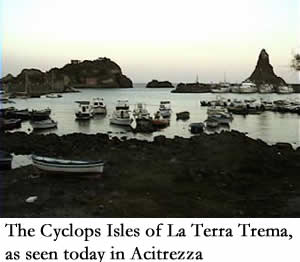

A short-list of cinematic sites includes Savoca, near Taormina, which substituted for Corleone, the birthplace of the Sicilian Mafia, in Coppola’s The Godfather trilogy. There’s also Acitrezza, the coastal village from  Visconti’s La Terra Trema whose harbor is still framed by the stunning Cyclops Isles mentioned in The Odyssey. And Sirena, the Aeolian island just north of Sicily that is named after Homer’s Sirens, and whose beach is the setting for the charming Il Postino. (That beach is partially gone today, thanks to the stream of tourists carting away knapsacks full of souvenir sand.)

Visconti’s La Terra Trema whose harbor is still framed by the stunning Cyclops Isles mentioned in The Odyssey. And Sirena, the Aeolian island just north of Sicily that is named after Homer’s Sirens, and whose beach is the setting for the charming Il Postino. (That beach is partially gone today, thanks to the stream of tourists carting away knapsacks full of souvenir sand.)

Per meter of celluloid, Giuseppe Tornatore’s The Star Maker hopscotches across more classic Sicilian villages than any movie I know. Even the names are seductive: Blufi, Polizzi Generosa, Cefalu, Petralia Soprana. Who can resist such a menu?

4. Be certain that the village you expect to find actually exists in real life (as opposed to reel life).

Case in point: Italy’s coastal town of Rimini, the location of Fellini’s unforgettable Amarcord. Nestled on the western edge of the Adriatic, it seems so inviting on screen, so loaded with genetically simpatico characters, that I once felt compelled to pay a visit myself. It’s also the town of Fellini’s birth, so it seemed oddly appropriate, back in 1994, that I would plan my trip there after attending Fellini’s funeral at Cinecitta Studios. I wanted to recapture the Amarcord magic I had found in the film.

Alas, when I arrived in Rimini, all I found was that the magic had vanished.

Alas, when I arrived in Rimini, all I found was that the magic had vanished.

The town’s seaside boardwalks and beaches were stunning enough, but who could ignore the steady invasions of Serbo-Croatian and German tourists crowding the views? Amarcord’s Grand Hotel, where Fellini’s characters came “to taste the honey of love,” was still handsome and standing, but its haunting grandeur had been swept away by decades of day-trippers and visiting corporate functionaries.

I managed to locate Amarcord’s Fulgor Cinema, too, where the young Bopo tried to seduce the mysterious and exotic Gradisca, but I almost missed it. Its once boastful marquee was drowned out by a tidal wave of chic boutiques and neon signs.

Where had the magical village of Amarcord gone? Clearly, it had disappeared in the long-discarded sets of Sound Stage 5 of Cinecitta, the place where Fellini shot nearly all his films, and the place where the director’s casket was eerily resting the day I visited his hometown. Even in death, Italy’s great trickster had fooled me into a visit, and I left Rimini feeling a bit betrayed.

5. Commit to visiting the one village that you absolutely fall in love with, and plan your trip around it.

For me, this was the village featured in the most unabashedly romantic Sicilian movie of all, Tornatore’s Cinema Paradiso. I especially loved its piazza, with its broad open pavement framed neatly by two church bell towers, and crowned with a simple fountain around which  all the villagers’ lives converge.

all the villagers’ lives converge.

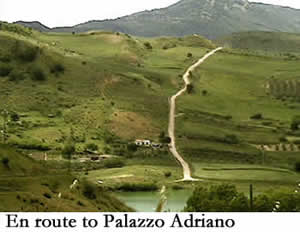

The name of the village was Palazzo Adriano, and a bit of Googling determined it was less than two-hour drive south of Palermo. It also revealed that the town’s Piazza Umberto (an ubiquitous name for Italian squares) did indeed exist in situ just as it appeared in the film.

And so, last May, I booked my flight. It was a good time to visit Sicily, before the high tourist season and the sweltering heat swooped down upon the island. Maybe I’d have better luck on this trip than I did in Rimini 15 years earlier.

6. Upon arriving in the village, head for its main piazza.

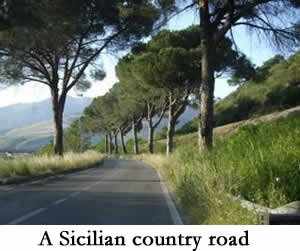

Palazzo Adriano is tucked into the rolling, rocky hills of central Sicily, and after driving down a boulevard of poplars and bearing right at the “Il Centro” sign, our little Ford Fiesta pulled into

Palazzo Adriano is tucked into the rolling, rocky hills of central Sicily, and after driving down a boulevard of poplars and bearing right at the “Il Centro” sign, our little Ford Fiesta pulled into  the famous square.

the famous square.

It all seemed instantly familiar: the imposing Byzantine church and bell tower, the octagonal fountain with its lion-mouthed well spouts, the panoramic spread of sun-bleached cobblestone that serves as the proscenium for village life. Just as it was in the movie.

But where were the villagers? Save for an ice cream truck ambling out of the square, leaving a bored little girl to finish her cone, the piazza seemed strangely deserted under the blazing Sicilian sun.

7. Take a few moments to imagine the movie.

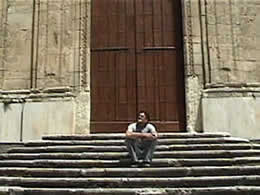

I walked over to the steps of the piazza’s main church and sat down, unable to turn off the projector running in my head.

These were the same steps, I remembered, where the film’s young Salvatore waited in the pouring rain for his girl to show up. Over there was the wall where Alfredo the projectionist

These were the same steps, I remembered, where the film’s young Salvatore waited in the pouring rain for his girl to show up. Over there was the wall where Alfredo the projectionist  screened the town’s first outdoor movies to a packed piazza. And over there, across the square, was where The Cinema Paradiso burned to the ground.

screened the town’s first outdoor movies to a packed piazza. And over there, across the square, was where The Cinema Paradiso burned to the ground.

At the risk of adding even more saccharine to the scene, I should note that these memories came accompanied by the great swelling strains of Ennio Morricone’s majestic score. Which was rather convenient, since I had left my iPod at home.

8. Find a village local to show you around…

After a few moments, my trip down memory lane was rudely interrupted by the all-tooreal soundtrack of a half-dozen old geezers gabbing away across the piazza. One of the fellows looked as if he’d been sitting around long enough to grow roots. Would he perhaps recall the making of Cinema Paradiso 20 years ago?

“Why wouldn’t I remember” he replied when we introduced ourselves. “Am I that ancient?” He pointed toward the fountain. “They set up right there for a few of weeks. I tried to sneak into a couple of scenes, but I guess they couldn’t afford me.”

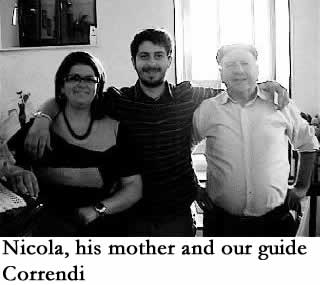

His name was Nicolo Correndi (left) – “Correndi” to his friends – and soon he was escorting us down the town’s cobbled streets, across a small bridge and into a trattoria that was “the finest in Sicily.” Or at least the finest that was still open for lunch.

His name was Nicolo Correndi (left) – “Correndi” to his friends – and soon he was escorting us down the town’s cobbled streets, across a small bridge and into a trattoria that was “the finest in Sicily.” Or at least the finest that was still open for lunch.

9. …And, if you’re lucky, he’ll lead you to someone who took part in the movie.

A Casa Vecchia (right) is owned by the Grana family, whose three sons help the mother cook and run the bed and breakfast upstairs. One of them, it turned out, was just the fellow I was looking for: an actor in Tornatore”s film with a few stories to tell. As Nicola Grana

A Casa Vecchia (right) is owned by the Grana family, whose three sons help the mother cook and run the bed and breakfast upstairs. One of them, it turned out, was just the fellow I was looking for: an actor in Tornatore”s film with a few stories to tell. As Nicola Grana

(below) served up the local specialties – pasta with breadcrumbs, pine nuts and raisins accompanied by a steady flow of ink-black Nero d’Avala wine — he told us how proud he was to appear in a small scene in  the film at the age of nine.

the film at the age of nine.

“Tornatore wanted to cast the characters in the movie from the villages of Sicily itself, and I think the film was a big success because of this,” he explained, adding that the child star of the movie, Salvatore Crescio, was in fact born in the village. “I played the kid who sat squirming in a chair by the cow pens while he got his hair cut. I think the scene ended up as short as my hair.”

Now 30, Nicola was in the midst of preparing a university thesis on a particular problem facing a host of villages throughout Sicily and Italy, one involving an entirely different kind of foreshortening. “When we made Cinema Paradiso, our town had over 5,000 permanent residents. Today, we have less than half that, and most of the young people have left. Our villages here are dying.”

We talked with the brothers for another hour before saying our goodbyes and preparing once again to face the country’s other great unsolved challenge: Sicilian drivers. At least we were still sober. We promised we’d continue our conversation from America.

10. Upon returning home, send your village friends a token of your thanks. Keep the spirit of the piazza alive.

We arrived back in Los Angeles a week later, and I couldn’t get Nicola’s project out of my head. It addressed a future that Sicily’s politicians and urban elite seemed reluctant to confront: How does the island save its ancient villages from a slow, imminent demise? The need to attract new and younger working generations is real; rural Sicily, after all, is full of piazzas that are full of old age pensioners, not to mention a fair share of unemployed youth.

We arrived back in Los Angeles a week later, and I couldn’t get Nicola’s project out of my head. It addressed a future that Sicily’s politicians and urban elite seemed reluctant to confront: How does the island save its ancient villages from a slow, imminent demise? The need to attract new and younger working generations is real; rural Sicily, after all, is full of piazzas that are full of old age pensioners, not to mention a fair share of unemployed youth.

Nicola’s idea is for his village to market itself more aggressively as the site of one of the world’s most beloved Italian films. But I worry that too much tourism could ruin the sleepy village as quickly as it tries to save it.

Still, it’s tempting to imagine how the town might have played host to a 20th anniversary celebration of the making of Cinema Paradiso, a milestone which passes this year. Tornatore and his actors would be in attendance, of course, and the movie could be screened outdoors in Piazza Umberto, just like Alfredo did for the villagers in the film itself. Afterwards, Nicola and his family could help host a gala dinner at – where else? – the finest trattoria in Sicily.

(In another 20-year milestone, Tornatore’s new Sicilian epic “Baaria,” about three generations of life in the director’s native Sicilian village of Bagheria, will become the first Italian film in two decades to open the Venice Film Festival on September 2. The film stars Monica Bellucci and Michele Placido, and is one of Italy’s costliest ever, with a $30 million price tag.)

(In another 20-year milestone, Tornatore’s new Sicilian epic “Baaria,” about three generations of life in the director’s native Sicilian village of Bagheria, will become the first Italian film in two decades to open the Venice Film Festival on September 2. The film stars Monica Bellucci and Michele Placido, and is one of Italy’s costliest ever, with a $30 million price tag.)

Whatever Palazzo Adriano’s fate – whether the village survives, grows, or quietly dies away – I’ll always remember it as it was in Tornatore’s film: full of zany characters and young lovers and life teeming around the piazza.

One afternoon, I sat down and sent photos of our visit to Nicola and his brothers and mother, and to Correndi and his “boys.” It made me feel I was part of a town I’d known for 20 years, as if I’d actually lived in a favorite film with a few old friends.

And that’s a very comfortable fit indeed.

PHOTOS OF ACITREZZA, THE SICILIAN COUNTRYSIDE, PALAZZO ADRIANO AND ITS VILLAGERS WERE TAKEN BY JAMES ULMER AND JONATHAN HANDEL.