Reconciliation: Mandela’s Miracle is an 88 minute HD documentary by Michael Henry Wilson. Once considered a “terrorist,” Nelson Mandela saved his country from bloody civil war and dismantled the system of apartheid through the spirit of reconciliation.

Reconciliation: Mandela’s Miracle is an 88 minute HD documentary by Michael Henry Wilson. Once considered a “terrorist,” Nelson Mandela saved his country from bloody civil war and dismantled the system of apartheid through the spirit of reconciliation.

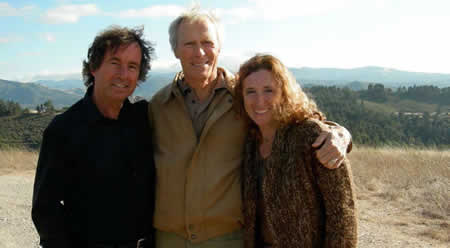

In this 88 minute documentary, witnesses give dramatic testimonials along with potent archival footage. Clint Eastwood, one of the film’s interviewees, sums it up simply: “The world needs people like him.”

www.reconciliation-mandelasmiracle.com

Bijan Tehrani: What inspired you to make Reconciliation: Mandela’s Miracle? There are quite a few interesting figures and celebrities appearing in your film, please tell us about them and the value they add to Reconciliation: Mandela’s Miracle?

Michael Henry Wilson: “Reconciliation: Mandela’s Miracle” is a project that has been percolating for years. It started taking shape in August 1999 during a private audience with the Dalai Lama when I presented him with a copy of my documentary “In Search of Kundun,” which includes an in-depth interview with him. He asked what my next project would be. I mentioned that I wanted to  focus on the spirit of reconciliation, a theme that concerned the survival of mankind.

focus on the spirit of reconciliation, a theme that concerned the survival of mankind.

His immediate response was a question: “Have you met Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu? You have to go and talk to them. Remember that it all started there in South Africa, with Gandhi.”

It took ten years for the project to come together. Even though our financing fell through a few weeks before the shoot, my wife/producer and I were committed to see it through, no matter what. By then, I knew that the South African story of reconciliation touched people in every sphere of life, from the townships to the halls of power — that it challenged the victims of apartheid as much as the perpetrators of violence. The story had to be woven as a tapestry, incorporating insights and experiences from a wide palette of witnesses. I realized as I was filming them that their emotions were so powerful, so eloquent, that there was no need for a narrator. Let them tell the story, however complex and painful, in their own words.

I did include one outsider in the choir: Clint Eastwood, who happened at the time to be filming “Invictus,” about the 1995 Rugby World Cup — an event that allowed Mandela to bring together the black and white communities in a stunning moment of national fusion. Eastwood, who has been a friend and colleague for many years, encouraged me to expand my canvas in order to capture the  diverse faces and voices of South Africa’s liberation, from the dark days of apartheid to the new era of black majority. He shared my conviction that today’s world needs leaders like Mandela if we want to escape the deadly logic of “an eye for an eye.” My hope is that “Reconciliation” allows the viewer to experience very concretely the many facets of Mandela’s “miracle.”

diverse faces and voices of South Africa’s liberation, from the dark days of apartheid to the new era of black majority. He shared my conviction that today’s world needs leaders like Mandela if we want to escape the deadly logic of “an eye for an eye.” My hope is that “Reconciliation” allows the viewer to experience very concretely the many facets of Mandela’s “miracle.”

Bijan: There have been a few documentaries made on Mandela, what sets “Reconciliation: Mandela’s Miracle” apart from them?

Michael: This is a film shot in South Africa in 2009 and finished in 2010, seventeen years after the end of apartheid. It is a look at the roots of the struggle and the transition from a tyrannical system to democracy but with a current perspective on the state of the Rainbow Nation. It is not a bio pic but a reflection on Mandela’s legacy as it relates to the world today. Every filmmaker has his or her own vision and a way of telling a story, and that in and of itself brings new life to the subject, hopefully so in our case! This one is a colorful story combining emotion and reflection as it rests on the synergy of cinema, sports and world politics.

I have also found that there is an incredible information gap in the public, even among the children of South Africa who were born after the end of apartheid. Everyone knows the name of Nelson Mandela, but not many today know the details of the history he shaped. This film helps people to remember a history that should never be forgotten, and to look to the exemplary men and women of South Africa who will be an inspiration for generations to come.

Bijan: Please tell us how about your approach in making “Reconciliation: Mandela’s Miracle.”

Michael: The idea was to compose a plural, polyphonic ensemble piece that gives a voice to diverse South African personalities. This meant calling upon survivors and witnesses, from all communities, to provide insights, anecdotes, memories, and sometimes dissenting viewpoints. My key image was that of a choir that would include people who have all contributed to the reconciliation process in one way or another, small or big — whether they shared Mandela’s captivity at Robben Island, worked in his security detail when he became president, been part of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee, helped draft the new constitution, or had been inspired by his leadership when he supported the Springboks, one of the most hated symbols of apartheid.

To anchor these testimonies, we revisited certain key places of the freedom struggle, notably the Robben Island penitentiary and the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg… as well as Soweto and several townships in Cape Town that are teaming with both life-affirming activity and the despair of extreme poverty. Amidst these tin shacks you come face-to-face not only with the country’s despair but also its hopes and current challenges. As the epilogue of our film suggests, Mandela’s legacy is the one beacon that inspires reasonable optimism about the future. In many ways, the destiny of South Africa appears to be a harbinger of what the entire planet might be like in the middle of this century.

Bijan: Please tell us about the research stage of your project.

Michael: This consisted, before and during the shoot, in selecting and approaching the members of our “choir,” making sure that their personal history would fit in the arc of our main story: the process of reconciliation. Surprisingly, quite a number of them had written books about their own experiences and this provided a trove of information when I was scripting the interviews. The witnesses’ testimonies were so strong and so pertinent that practically every interviewee ended up in the finished film.

During the editing period, research focused on the availability of archival footage about South Africa’s history. We combed through more than a hundred hours of stills, TV news, newsreels, documentaries from South African and international archives to select relevant images. We were surprised to find that so many incidents of the country’s tumultuous history…some extremely violent…had been covered by cameramen, at least from the 1970s on. The main challenge, of course, was that there exist very few filmed images of Mandela before his release from prison in 1990. However, we were able to make use of two key documents, a clandestine interview Mandela gave to a British journalist in 1961 when he was in hiding, and a glimpse of him working with a shovel in the Robben Island quarry that was captured by the camera of a Dutch visitor.

During the editing period, research focused on the availability of archival footage about South Africa’s history. We combed through more than a hundred hours of stills, TV news, newsreels, documentaries from South African and international archives to select relevant images. We were surprised to find that so many incidents of the country’s tumultuous history…some extremely violent…had been covered by cameramen, at least from the 1970s on. The main challenge, of course, was that there exist very few filmed images of Mandela before his release from prison in 1990. However, we were able to make use of two key documents, a clandestine interview Mandela gave to a British journalist in 1961 when he was in hiding, and a glimpse of him working with a shovel in the Robben Island quarry that was captured by the camera of a Dutch visitor.

Bijan: How did you come up with the visual style of the film?

Michael: Although the inequities of apartheid are necessarily dwelt upon through testimonies and archival footage, I wanted our HD images and sounds to celebrate the extraordinary beauty of the land and its multiple African cultures. This is the reason I chose French cinematographer Dominique Gentil, who started his career shooting documentaries in Africa and later became the director of photography of the continent’s top filmmakers. Watching his work on Ousmane Sembèbe’s magnificent Moolaadé, I knew he would be the right man for the job. He would be just as expert at capturing unique images amidst the squalor of the townships as at lighting our interviewees in carefully chosen locations that would express their world or frame of mind within the shot. He is also an expert in aerial photography (Winged Migration) and it was a rare pleasure to set up and compose helicopter shots, particularly over Robben Island and Cape Town’s majestic Table Mountain, within a ridiculously tight budget.

Bijan: Has Mr. Mandela seen Reconciliation: Mandela’s Miracle and what has been his reaction to it?

Michael: We have not yet shown the film to Mr. Mandela, as it has just been completed about one month ago. However, we look forward to the time when we can screen it for him.