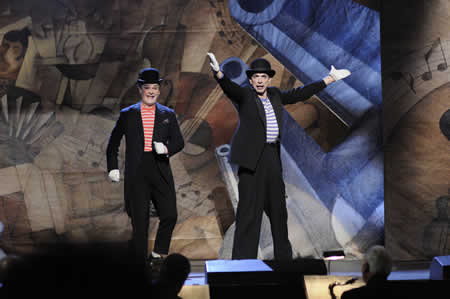

Paper Birds is the sale of a group of Vaudeville performers caught in a war that has taken away everything they had and left them starving. Musician Jorge del Pino, ventriloquist Enrique Corgo, singer Rocio Moliner and an orphan named Miguel make up an unlikely family of lost souls, struggling to get by one day at a time, sharing their joys and sorrows and their only escape from the misery around them: their music. As it turns out, when bread is scarce, applause can really hit the spot.

Paper Birds is the sale of a group of Vaudeville performers caught in a war that has taken away everything they had and left them starving. Musician Jorge del Pino, ventriloquist Enrique Corgo, singer Rocio Moliner and an orphan named Miguel make up an unlikely family of lost souls, struggling to get by one day at a time, sharing their joys and sorrows and their only escape from the misery around them: their music. As it turns out, when bread is scarce, applause can really hit the spot.

Living among the victorious and the vanquished, they’re too busy looking for something to eat and a bed to sleep in to worry about making it big. But right away they are put to the test and forced to make decisions that will place their lives in jeopardy.

At a time filled with intrigue and dangers that leave them no choice but to takes sides and put themselves in harm’s way, they do the best they can to find a place to sleep where they won’t be afraid. Wherever that may be.

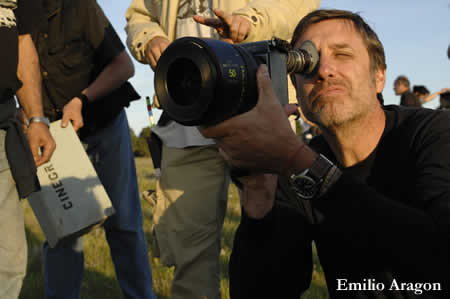

Last week we had an opportunity to speak to Emilio Aragon, director of Paper Birds.

After a long career both in front of and behind the television cameras, Emilio Aragón ventures into cinema for the first time as a director with his first film, Paper Birds. Written by Fernando Castets and Emilio Aragón, Paper Birds follows the adventures of a group of Vaudeville performers and in particular a strange, one-of-a-kind family. The film features an experienced cast of actors including Imanol Arias, LLuís Homar, Carmen Machi and Roger Príncep. The film was shot in March, April and May of 2009 in Madrid, Chinchón, Tembleque, Colmenar de Oreja and Almagro and is presently in the post production stage. It is due for release in 2010. The original soundtrack was composed by Emilio Aragón and performed by the Madrid Orchestra and Choir and renowned guest artists like violinist Ara Malikian, Kepa Junkera playing the trikitixa, and guitarists Pepe “El Habichuela” and Josemi Carmona.

BIjan Tehrani: How did you come up with the idea of making Paper Birds?

Emilio Aragon: I thought that there was a generation of comedians in Spain that were owed a tribute. So that was the main basic idea and I worked on this over the past ten or twelve years and I had the opportunity to work with actors and comedians from my father’s generation. Between scenes, I could hear the actors talk about anecdotes and stories and there was a curious thing between the anecdotes and stories, seeing as how they all dealt with stage, dressing rooms and theatres. So, I started writing down ideas. When I sat down with Fernando Castets, who co-wrote the movie with me, we felt that there were many things that had to be said concerning the civil war and the post-civil war; so we mixed these ideas and the result was Paper Birds.

BT: Looking at Paper Birds, it seems that it is a very difficult film to make because you’re dealing with the different points in the life of a person and maintaining continuity; how did you overcome these issues when making the film and allow the film to flow together as well as it does?

BT: Looking at Paper Birds, it seems that it is a very difficult film to make because you’re dealing with the different points in the life of a person and maintaining continuity; how did you overcome these issues when making the film and allow the film to flow together as well as it does?

EA: One of the things that I thought was very important to deal with was the emotional aspects of the main character, Jorge Del Pino, in which during the entire movie he has to live with a terrible pain. One of the things that this movie talks about, and in a way I feel that it is universal, is how can you manage to wake up every single day after losing a wife, a son or a brother or sister and walk as if nothing has happened? So this is the base and truthfulness of the film. There had to be truth in every single thing; in the dialogue, in the comedy and even in the real situations of our country in 1920’s and the 1930’s. I feel that all of these things allow the film to flow in a very nice way. In addition to this, the mastery of the actors contributed greatly as well. With Imanol Arias, who plays the main character, Lluis Homar, and Roger Princep, who plays Miguel; you really believe that these three characters are a family and I believe that they have done a wonderful interpretation. There was strong chemistry between those three and I think this proved to be very important.

BT: How did you go about casting the film?

EA: It was a certain mix. I had two or three ideas for actors for the main role of Jorge Del Pino, but the casting director, from the beginning, had Imanol Arias in mind. We needed, because of the role that Lluis Homar plays of Enrique Corgo (the ventriloquist) an actor with a lot of sense and Lluis Homar is very complete; we also needed a feminine side to play that role and he did it very perfectly. The boy took a long time to cast, but the second week of casting Roger Princep appeared and it was like day and night from the rest of the kids. He had something that I think was very important and he was very emotionally intelligent. Also what made him good for the role is that he, in real life, is an orphan; he lost his father when his mother was pregnant with him, so this idea is also in the movie. I had to be very careful when directing him because I had to avoid touching on his personal situation.

BT: I know that you have had acting experience, so how did your history as an actor help you with directing the actors in your film?

EA: It absolutely helps because what an actor has to struggle with during the shooting of a movie like this (one that was shot over ten weeks, when you have to shoot for twelve hour days), it helped me in a certain way because I knew when to push and when not to push an actor to a certain point in terms of what you want for a character. So yes, my acting background absolutely helped.

BT: What kind of research did you have to conduct for this film?

EA: We did a lot of research concerning the historical part of the movie in terms of the political side as well as the artistic side in terms of what kind of music was played during that era and what kind of comedy they had in that era. The art director researched what the theatres looked like in those days and I also researched a lot with my father because he lived through those times.

BT: How challenging was it to make a film that took place during this time period?

EA: Every movie or every project is difficult; there are a couple of anecdotes in the movie that touch on this. The ending of the movie has a ship that we were going to shoot in the south (all of the ships that went to America departed from Barcelona), but we were not able to shoot there because it was too expensive, so we had to switch to a train. In a certain way, I feel that we won because I have always loved train stations and I feel that it is more romantic. But the second week of shooting we were denied to shoot in the old train station, so we had to think of a third alternative. But we finally managed to sign the permit and shoot at the station. So it seems that the 10 week shoot was actually a nine week shoot—that dilemma provided a break for a week. I was lucky to have a fantastic team of workers.

BT: How much did the memories of your father help you in making this film? EA: There are three of four anecdotes in the movie that happened in real life to my father: The one dealing with the unicycle man that falls from the stage, the rice in the pocket of the boy, and a couple more incidents actually happened. What I was really careful with was that even though there is no aroma in a movie, I really wanted to try to transmit what the dressing rooms looked, sounded, and smelled like, as they were described by my father. So the stories that my father told me were a big influence in the movie.

EA: There are three of four anecdotes in the movie that happened in real life to my father: The one dealing with the unicycle man that falls from the stage, the rice in the pocket of the boy, and a couple more incidents actually happened. What I was really careful with was that even though there is no aroma in a movie, I really wanted to try to transmit what the dressing rooms looked, sounded, and smelled like, as they were described by my father. So the stories that my father told me were a big influence in the movie.

BT: This film reminds me a lot of the neo-realistic films of Italy; would you agree with this comparison?

EA: I love the movies from that era; the Spanish movies, Italian movies and French movies. When I sat down with the team, I had a very clear vision that the movie had to be placed in a classical way; the art direction, the cinematography and the camera movement all had to be very classical.

BT: The different themes of the film come together very well; the comedic themes, the political themes and the emotional themes all flow nicely. Because of this, the film isn’t overly emotional or too comical, how difficult was it to effectively balance all of these themes?

EA: When we sat down to write the movie, we were very clear that this was not going to be a political movie. From the beginning, we wanted to talk about these people and what they had to struggle with. In 1940 Spain, the Second World War was going on and Spain was sort of a test for the Germans and the Italians. After the war, all of these actors emerged and there were different types of people; there were the people that had to leave the country, the people who stayed, and the people who wanted to leave but did not have a way to leave the country. So what we are talking about is also the freedom that these comedians and actor had before the civil war and how they were able to survive without these freedoms. But from the beginning, we knew that we did not want to make it political.

BT: Do you think your film has a chance of getting one of the final five nominations for the Academy Awards?

EA: For the Oscars, another movie was selected, and next Monday or Tuesday the nominees for the Golden Globes are going to be announced. The movie will be screened in Los Angeles, when the movie premieres here in the United States. The real reward for me comes in the reactions of the audience. Screenings in Montreal and Tokyo showed that the connections from the audience are absolute. I was surprised when the lights went on in Tokyo and I could see people crying in the movie theater, and we got a lot of applause. So moments like that are the real prizes and awards.

BT: What are your future projects?

EA: We are writing a movie right now with Fernando Castets. It is not a period movie, it is situated in the present and it is a movie about forgiveness. We will probably have a final draft in January. We have a lot of ideas and we want to shoot it next year, but first, we want to finish this film and finish touring and then we will focus on the next project.