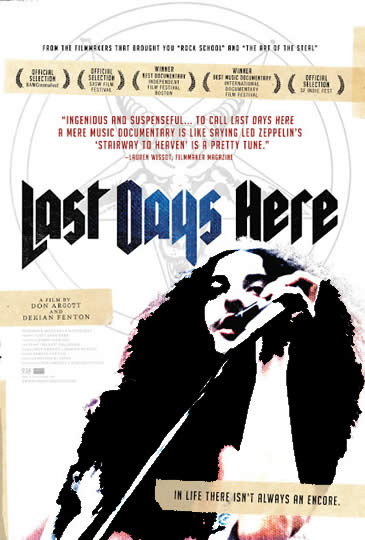

LAST DAYS HERE, the new documentary from Don Argott and Demian Fenton (THE ART OF THE STEAL, ROCK SCHOOL), is a raw, yet unexpectedly touching chronicle of cult metal legend Bobby Liebling’s bid to resurrect his life and career after decades wasting away in his parents’ basement.

LAST DAYS HERE, the new documentary from Don Argott and Demian Fenton (THE ART OF THE STEAL, ROCK SCHOOL), is a raw, yet unexpectedly touching chronicle of cult metal legend Bobby Liebling’s bid to resurrect his life and career after decades wasting away in his parents’ basement.

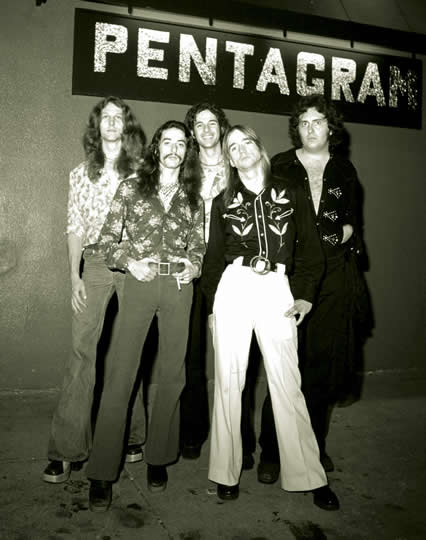

Bobby Liebling made his mark in the ‘70s as the outrageous frontman of Pentagram, a “street” Black Sabbath whose heavy metal riffs once blew audiences’ minds. But various acts of self-destruction, multiple band break-ups and botched record deals eventually condemned his music to obscurity. Now in his 50’s, wasted by hardcore drug use and living on the charity of his ever-patient mother and father (a former Nixon advisor), Bobby’s music is finally discovered by the heavy metal underground. With the help of fan-turned-manager Sean “Pellet” Pelletier, Bobby struggles to overcome years of addiction, loneliness and broken dreams to get back on stage again. For over three years filmmakers (and metal musicians) Argott and Fenton are witnesses to his unbelievable journey, following the triumphs and downfalls of this underground icon at the crossroads of life and death.

Bijan Tehrani: Last Days Here is a very interesting and entertaining documentary—it is almost Hitchcock-ian! Did you have a script for this at all?

Demian Fenton: Not at all! I think what you are mentioning about presence of tension in the film, like a Hitchcock film, is due to Bobby’s real life. I mean, at any minute of Bobby’s life, anything can happen and, at any minute, he could be dead or he could be in epic trouble. There is a documentary called “The Bridge”, about people jumping off of the Golden Gate Bridge, and large portions of the film are just these long shots of people walking back and forth on the bridge and you wonder, is this going to be the person who jumps next? There is this awful pit in your stomach the whole film, and I think in some way that tension is definitely here with Bobby’s story.

BT: Do you agree that Last Days Here is more about Bobby’s character than his music?

DF: Yes, and early on that was our goal. Making a film that wasn’t necessarily a Rock ‘n’ Roll documentary, but more about life and redemption and the redemptive power of music, and not necessarily about music. I think what is interesting about this movie is that the character Sean has his musical goals for Bobby and himself, but while making the film we learned that Bobby had other goals and that music may have been helped to achieve them. His goals were just to live and have a life, and that was a bit more interesting to us than following a musical journey.

BT: Bobby has a very sympathetic and likeable character in the film, even at the early part of the film when we see him constantly using drugs. There is something about him that has us ending up liking him. Maybe by self-destruction he is trying to find his creativity, like when we detonate mountains in order to find precious stones.

DF: I think it depends on the viewer. Some viewers do not have patience for addicts, but I think when we get the right viewer to watch and you see that everyone involved saw a grimmer something in Bobby and saw that he was ready and willing to go on a journey. In many ways, we hoped that he would succeed—we certainly hoped that he would do better, but we were not sure what was going to happen. I think when we walked to his parents’ house, where he lived, we were sympathetic to the whole situation, so hopefully that came across in the film where you root for this guy and you see in his eyes and his heart that he does want to live and he does want to get out of the sub-basement.

BT: Sometimes self-destruction can help someone find themselves.

BT: Sometimes self-destruction can help someone find themselves.

DF: I think it is almost a level deeper with Bobby, where that self-destruction doesn’t feel like it is this separate choice that he is kind of indulging to become more creative; to me, when you see Bobby, what is so alluring about someone like Bobby is that he is so sincerely at home in this grimy world of Rock and Roll, drugs and sex, and I say it all the time: he is not like this guy who is playing a Rock and Roller, he is Rock and Roll and he does not have that filter that says, “Hey, I am going to get high now and try to be inspired!”. He is just going to live like that and be that. He reminds me of someone like Lemmy. Even though Lemmy made some money in his career, you know you can’t see these guys doing anything else or living any other way. This is what they are born are to do and this is what they are.

BT: Another magical point about your film is that everyone is so comfortable in front of the camera. How did you manage to achieve this? For example, Bobby’s parents are just themselves on camera.

DF: I think there are a couple of answers to that. One, I think, is that Bobby’s scenario in his life when we met him was pretty negative and that whole house was pretty dark and there were a lot of negative things happening there. People would come over to do drugs and kind of head out, some would leave and some would stay there and were kind of down and out. He did not have another place to stay and I think, for Bobby’s parents at least, us coming down there and being a positive force was something that was very welcome. I mean, we weren’t there to smoke crack with Bobby, we were there to listen to records and talk about life and that was one factor that let those doors open. I think the second factor is, that if you are a documentary filmmaker, it is your job when you walk into a situation—as shocking as it may be—to take it seriously and respect the fact that people are living like that and figure out how and why they got there. You can’t be too shocked or amazed, or judgmental. I love Rock and Roll, and this is a story close to my heart where I could walk into it and say that I could easily be Bobby, and the rest of my friends, we could all be Bobby at some point in our lives. To walk in there with that open mind and keeping that judgmental kind of vibe checked at the door, I think that really helps no matter what story you are telling—it helps your characters open up to you.

BT: How difficult was it to make this film?

DF: It was a tough film to make, but it was kind of interesting in the way that it happened. We did not get any funding for this, so this is just a couple people picking up cameras and doing everything for no money and, during the making of the film, we always clearly felt that this was making things harder. In a way, though—with the pace of Bobby’s life and the way the events unfolded—we needed that time to just slowly move along, and we did not have anyone telling us that the film needed to be done. We did not have investors who were worried about whether or not this guy was going to die or not, and we just kind of worked hard. It was always in the background, and many times it had to rise to the foreground, but I think cruising along at the speed that we did without resources was actually a benefit for this film.

BT: Watching the film, I felt the film itself had a “Hard Rock” and “Rock and Roll” rhythm. I could see that in both the camera work and the editing.

DF: I think what is cool about it is that I did a lot of the shooting, and mainly I am an editor. We just went with this feel that it is just this intimate guy with a video camera hanging out in a field, so in a lot of ways it is very Rock and Roll: just grab the camera go and try to capture this story the best that I can, even though I am not really a shooter. It has this gritty feel and it was shot on DV in an era where everything was turning into HD, and it maintains this kind of interesting feel that is gritty and intimate.

BT: You have a happy ending with this film; Bobby is clean from drugs and is married with a newborn baby. I was relieved for Bobby but, at the same time, I wondered if he would become an ordinary guy and lose his creativity and all of that. What really happened to him?

DF: Since the film happened, Pentagram has recorded a record and he has been all over the world—he even sat in on a Q&A session the other day. Before he kind of came out of the basement, before this documentary had gotten started, he had been to four states in the U.S. Since then, he has been all over the world! He has been all over the United State and he has another record out. There are rumors he is going to work on another record, but he has his family life going on as well, so it really is this kind of story about this eighteen year old guy who put his life on pause for thirty years, and now he is getting back to it. He is growing in many dimensions, living a normal life, getting responsible and also traveling around the world and playing Rock and Roll.

BT: There are two parallel stories in Last Days Here, one is about Bobby’s life, his struggles, his love life and everything else, and one is about Sean, who wants to put Pentagram’s members back together one more time. It is always hard to blend two stories together, so how did you go about doing this?

BT: There are two parallel stories in Last Days Here, one is about Bobby’s life, his struggles, his love life and everything else, and one is about Sean, who wants to put Pentagram’s members back together one more time. It is always hard to blend two stories together, so how did you go about doing this?

DF: I think that we learned early on, and what made us interested about this movie, is that there were two journeys. We wanted to get this guy a page in the history books of Rock and Roll, so we needed a big show. We needed the accolades, we needed a record, and we always thought that that would be the story of the film and the trials and tribulations of that. Early on, however, we realized that Bobby’s goals were different; he wanted to live! His life had been on pause for so long, he wanted things like a place of his own and to get out of the house, like a regular twenty year old kid. So we knew that there was going to be this journey that happened simultaneously, but we also knew that each person had different goals. Bobby realized that he needed music and it could help him get through these tough times, and Pellet realized that, as much as Bobby needs music, he also needs love and affection. He has these different goals, so when we mapped it out we really did see it as two journeys. We were aware of the attention that it would bring when there were collisions and different paths that people wanted to have, but we also knew that at some point it would either crash and go up in flames, or come together in this beautiful way—which I think it does.

BT: What is your next project?

DF: We have a couple things going on. We have a film that John directed with the producer of Last Days Here, a woman named Sheena Joyce, and I was the editor on that film, which premiered at Sundance this year. The film is about nuclear power and it just tacked on to communities around the country and the larger nuclear power debate that we are having here. Also, we have a couple of other projects going around—some are music and some are not, but we just love great stories, so hopefully you will see more of that.

LAST DAYS HERE is playing at the Cinefamily this week