Parviz Sayyad actor, writer, film, theater and television director and producer is one of the most famous actors among the masses in Iran while among the film fans and film critics he is known films that he has directed and produced. Sayyad that started his career at 1960 in Iranian National Television is an Iranian example of what French new wave critics called an “author”, he creates his characters, writes his own screenplays and directs them with a recognizable style. One of the memorable acting performances in history of acting in Iran was by Parviz Sayyad, playing a leading part in a famous television series in seventies called and Dear Uncle Napoleon (directed by Nasser Taghvaii in 1977)

Parviz Sayyad actor, writer, film, theater and television director and producer is one of the most famous actors among the masses in Iran while among the film fans and film critics he is known films that he has directed and produced. Sayyad that started his career at 1960 in Iranian National Television is an Iranian example of what French new wave critics called an “author”, he creates his characters, writes his own screenplays and directs them with a recognizable style. One of the memorable acting performances in history of acting in Iran was by Parviz Sayyad, playing a leading part in a famous television series in seventies called and Dear Uncle Napoleon (directed by Nasser Taghvaii in 1977)

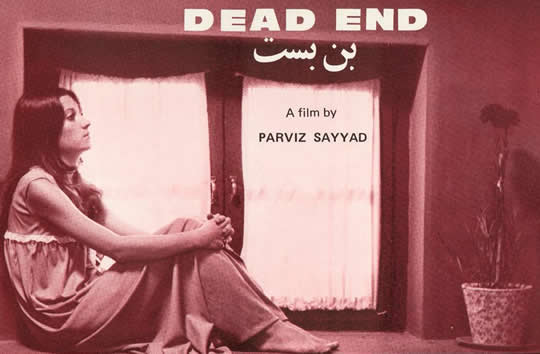

International Film Guide (1977), described Sayyad as “An extraordinary popular and vital member of the Iranian film world”, while Film Comment Magazine wrote, “in much of Sayyad’s work, he examines the lives of individual people caught up in political or social events which are beyond their control. In Dead End (1976), Mary Apick plays a lovesick girl wooed by an eligible young man, only to find her suitor a SAVAK agent whose mission is to arrest her brother. In Shahid Saless’ celebrated Far From Home (1975), Sayyad plays the part of a lonely Turkish immigrant laborer in West Berlin who is met with indifference when he tries to make friends with his German neighbors.

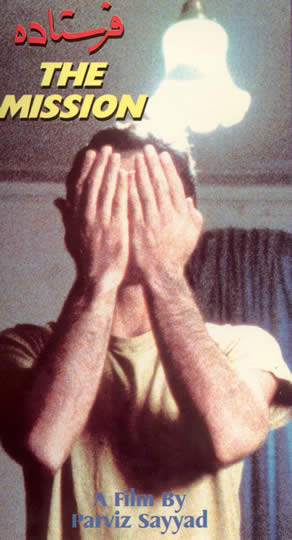

After moving to United States and living since then in this country in exile, Sayyad has directed two feature films, Frestadeh (The Mission – 1983) and Checkpoint 1987. UCLA is going to screen Dead End, The mission and Checkpoint during its Celebration of Iranian Cinema opening on April 14th.

Bijan Tehrani: The screenings of your film at UCLA was a surprise, a good surprise. I am assuming that we will see the same made-in-Iran films at this festival but dedicating a few days of UCLA celebrations of Iranian cinema to the films made by an Iranian filmmaker in exile is good news. What is your take on this move?

Parviz Sayyad: It was a surprise for me, too. Twenty years ago when UCLA was celebrating its first film series from the Islamic republic, I was among a group picketing outside the theatre. To us, the protestors, the whole thing seemed to be a cultural flirtation between UCLA and the Ministry of Islamic Guidance in Iran and to tell you the truth I have not changed my mind since. The other main objection that we had was the timing of these annual celebrations that were held in mid-February, the time when the Iranian government also had its state sponsored anniversary celebrating the inception of the so-called Islamic Revolution. In the past twenty years I have never participated in this annual event at UCLA and not even attended one screening as a film fan. But now the policy has changed and the date of the celebration of Iranian Cinema has moved from February to mid-April, otherwise you wouldn’t have seen me or any of my films.

BT: Dead End made in 1977, belonged to a movement that you started in your Tehran Little Theatre and of course there were other Iranian film directors that joined you in that movement. This was just two years before the Revolution. How did that movement start and how different was Dead End compared to the mainstream Iranian movies back then?

PS: I believe it was more than two years before the Revolution. The movement that you are mentioning started in 1973. A group of filmmakers, mostly young and educated, collectively resigned from organized unions of the film industry of the time, protesting the lack of support for progressive and innovative filmmaking. In those days, making a movie such as Dead End was a huge risk, not only politically but for the simple reason that no theaters were available to show those films for public screening. All movie theatres were either on annual contracts to show foreign films or reserved for mainstream Iranian cinema. Mainstream movies differed from new wave films not only because of their production values but also because they lacked cultural identity. They were mostly commercial, duplicates of Bollywood imports in both subject and form.

BT: You produced The Mission and Checkpoint in exile, how did you manage to make these two films? I imagine it must have been a huge challenge and why have you not made a third film in exile?

BT: You produced The Mission and Checkpoint in exile, how did you manage to make these two films? I imagine it must have been a huge challenge and why have you not made a third film in exile?

PS: Well it was a real challenge, I made The Mission in 1982 in New York with the help of a cinematographer friend who brought his 16mm film equipment from Germany and borrowed money from various sources. The Mission was very well received by audiences as well as film critics, but I lost all my resources four years later by making Checkpoint. Even the festivals, which praised and awarded The Mission, refused to show Checkpoint, some of them calling it too political. But that was not the real problem. The release of Checkpoint coincided with Khomeini’s Death Fatwa for Salman Rushdi. So it was doomed to be dumped because it was against Islamic fanaticism. In the meantime, something else emerged to make the film even harder to distribute. Almost all festivals and cultural centers including UCLA began dealing with the Islamic Republic, receiving annual film packages from Tehran. As time went by, the Islamic Republic became the only government with a state sponsored cinema in the world after the fall of the Berlin Wall. So Tehran became the only place with a lot of films to offer and a lot of money to bribe. Could I make another film against Islamic fanatics like checkpoint? I would not do it even if I could.

BT: The Mission created a controversy among audiences, many praised the film for its daring subject and a few complained that it cleared the Savak, Shah’s secret police. What do you think about that?

PS: That controversy was raised by some Iranians who were not happy with the contents of The Mission. I have hundreds of film reviews written about The Mission in my archives, and none of them make this kind of claim. Clearing the Savak, in fact is far from the meaning of The Mission and far from my intentions in making the film. The Mission is about two individuals, used and victimized by two different political systems.

BT: When I watched Checkpoint for the first time, I enjoyed its flow and clever story, but I was a little lost. I wanted to see who you sided with in the film and I could not find it. Later, I thought that this film is a model for democracy for Iranians, leaving one dictatorship and jumping into a tougher one. Was that your point?

PS: I like your interpretation, but that is a lesson that I have learned from Chekhov: observing the characters under equal light and allowing them to show their human qualities and even their weak points. You can see this same approach in all my three films being screened in the current UCLA film series, Dead End, The Mission and Checkpoint, with one exception in the last one. In Checkpoint, I am playing a part that carries all of my feelings and reasoning against Islamic fanatics. Isn’t that taking sides enough?

BT: Among the films that you have made as a producer and also as an actor are two films by the late Sohrab Shahid Saless, one of the greatest filmmakers from Iran that unfortunately passed away a few years ago. Those films are brilliant. How come we don’t see them in this festival and will there be a chance to see those films in the near future?

PS: I did not have any part in planning this film series at UCLA. They just invited me to participate with my three films and they said that they do not have any films officially sent from Iran and I accepted the invitation. But I believe that you are right about Sohrab Shahid Saless and I hope that UCLA arranges a tribute to him and dedicates an entire film series to Sohrab Shahid Saless, not just for the films he made in Iran but also for the films that he made in Germany, because he is considered a German filmmaker more than an Iranian filmmaker. As a filmmaker, Sohrab made more than ten films in Germany and only three films in Iran, one of which was a co-production between Iran and Germany. So, in reality he had made only two feature films in Iran.