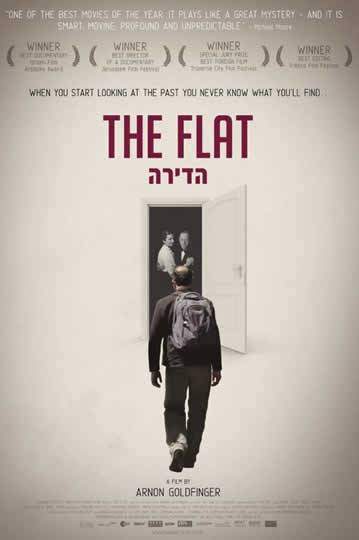

Arnon Goldfinger’s THE FLAT, a meticulously researched and immensely entertaining film that is a remarkable journey through history which gives a truly unique look at the way different generations viewed the Holocaust.

Arnon Goldfinger’s THE FLAT, a meticulously researched and immensely entertaining film that is a remarkable journey through history which gives a truly unique look at the way different generations viewed the Holocaust.

At age 98, filmmaker Goldfinger’s grandmother passed away, leaving him the task of clearing out the Tel Aviv flat that she and her husband shared for decades since immigrating from Nazi Germany in the 1930s. Sifting through a dense mountain of photos, letters, files, and objects, Goldfinger begins to uncover clues that seem to point to a greater mystery and soon a complicated family history unfolds before his camera. What starts to take shape reflects nothing less than the troubled and taboo story of three generations of Germans – both Jewish and non-Jewish – trying to piece together the puzzle of their lives in the aftermath of the terrible events of World War II.

Bijan Tehrani: What motivated you to make The Flat and what make this film relevant to our time?

Arnon Goldfinger: I view every film that I make as an unexpected journey, and I hope that the process of making it might be a process that will have an impact on my life. When I started filming The Flat I had a strong feeling that it was going to follow those two elements – but of course at the time, I could not guess how far it would take me.

I believe that almost everyone who sees the film asks themselves what they know about their parents’ or grandparents’ past. Or for people of an older generation – what did they pass on to their children? From the reactions of viewers around the globe, I learned that this feeling of lacking, of missing something essential in your own identity, is shared by many people from different cultures and ages.

Another thing is of course the experience of emptying out the flat of a relative. This is an experience that many have to deal with, at least once in their life, and needless to say it can be a deeply emotional experience.

BT: How challenging was making this film.

AG: I suppose that the basic challenge grew out of the fact that this was the first time that I became an on-screen subject. That was not a simple choice. The way in which the film developed led me to understand that I had to leave my position behind the lens. The main challenge actually was the story itself; its shuddering discoveries that produced many sleepless nights during which I deliberated over the question of whether it would be better to return the skeletons to the closet…

BT: Even we have seen so many film about this kind of subject, Flat has a unique approach and look, how did you come up with this approach?

AG: For me, making a film is an opportunity to reexamine my own beliefs, my thoughts, my pre-conceptions. I am trying to get the sharpest look possible at the reality as well as at myself. It is a hard task, you may even say an impossible one, because one cannot escape the fact that you are looking at reality through your own glasses. So I try cleaning my glasses the best I can, and more importantly, I try to be loyal to what I see. I believe that when you legitimate your own thoughts, it may lead you to new discoveries.

BT: When you see The Flat, it is like your own personal experience, what helped you to pass this feeling to your audience?

AG: One of the fundamental decisions during the editing process was to try to convey the events in the way I experienced them as closely as possible. That influenced the structure of the film as well as my narration. I believe that this “eye-level” approach helps the viewer to experience the film in the way I experienced it.

BT: Please tell us about visual style of the film.

BT: Please tell us about visual style of the film.

AG: I think that the tension between my need to tell a story and a reality that is often chaotic and unexpected, is perhaps what attracts me to documentary filmmaking. This tension also shaped the way the film was shot. For example the approach to light – It was clear to me that there is a conflict between the low light, the almost darkness inside my grandparents’ flat and the direct Israeli light that penetrates from the outside every time the window shutter is pulled up. We tried to pay attention to these nuances throughout the film. In a way the film becomes lighter as it develops. Almost till its end where the light becomes darker again. I believe this kind of cinematic thinking is more often found in fiction films than in documentary filmmaking. I also adopted a more narrative approach toward the structure of the film. You may notice that the film is built scene after scene, paying attention to the characters and their conflict in each scene employing narrative mode of analysis. However as this is a documentary one cannot really control or predict what will happen –and that almost always surprised me.

BT: What is your next project?

AG: Every film that I have made until now was not something that I could have imagined before I made it. I am toying with a few ideas for my next project, but based on my previous experiences, I will most likely be completely surprised.