Rod Cyrus is a young and talented professional photographer living in Iran. Rod was attracted to the art of Photography at the age of 23 and after receiving a degree in Computer Programming, he has been exploring the world of this art ever since. On spring 2010 Rod entered a group exhibition held in Paris along with 5 other artists.

Cinema Without Borders: What motivated you to become a photographer?

Cinema Without Borders: What motivated you to become a photographer?

Rod Cyrus: It first started with a fascination of one of the most basic phenomenon in life, and that is perspective and motion. I remember spending hours walking in the streets and just looking at everything and observing my surroundings. I will try to explain this fascination: you see when you walk past a tree that is between you and a wall, parts of the wall constantly come out from behind the tree to be visible to you, yet parts of the wall are going behind the tree to disappear just to come back in a moment to be visible again. Meanwhile, a different part of the tree is being revealed to you and some other part is hiding from your view.

These are all just very basic and common happenings to all of us that hardly anybody takes notice of, but to me it was like a dance going all around me and I loved watching and enjoying it. Naturally, I developed the desire to capture and share my visual experiments, and that’s how I came to be a photographer.

CWB: You are one of the rare photographers that has samples of work in most of the existing photography categories and I have to say, you show great work in all of them. How do you manage to that, and is there a category that is more in your interest?

RC: Well I think the experience of “Seeing” has no limit to it, and unlike many of my photographer friends who tend to take their camera with them only when they are going somewhere special, I like to photograph every scene that calls me to it. This is why I have so many categories, though not all of them were there at the beginning when I started my website.

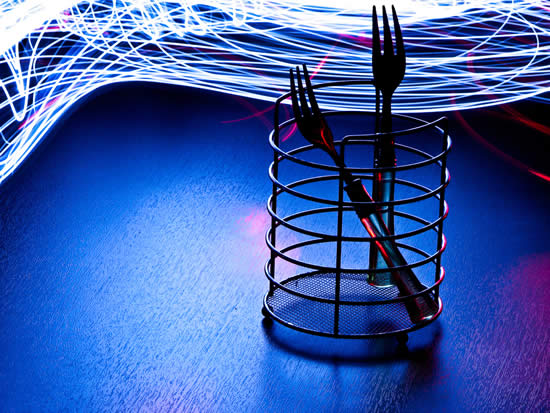

Yes, there are two categories that I like more than the rest, and they are “Lighting Room” and “Smoke”—both of which have a lot of motion to them and are similar in that aspect, but they are very opposite in another aspect and that is my control over the subject. In “Lighting Room”, I have all the control over the final picture, where-in “Smoke” I am as much of an observer as one can possibly be.

CWB: You have done amazing experiments with light in your photographs. Tell us about how you deal with light and experiment with it?

CWB: You have done amazing experiments with light in your photographs. Tell us about how you deal with light and experiment with it?

RC: I cannot imagine a light that is not moving. Of course, we all see and observe light as we are looking at things, but I see it always and constantly raining down on objects; bouncing back from them, fighting its way through some of them and constantly moving. Light is captivating, and I sometimes think of the process of taking pictures as capturing the experiment that light is having on these objects. When I do that, it is no longer me that is experimenting, it is the light that is having the experiment and I am just there to capture it.

CWB: You also have a lot of attention to the motion. In your Splash series, for example, I witnessed a motion that  had started before the camera captured the moment and continued after that. What attracts you to register the motions in your photographs?

had started before the camera captured the moment and continued after that. What attracts you to register the motions in your photographs?

RC: Again, in “Splash” the miracle of motion is happening, but this time I have partial control over the experiment. I start the motion, but after that I am, again, only an observer, helpless as to what happens next. It is like many other parts of life to me: you are free to make the decision whether or not to do something, but once you make that decision, you are going to have to live with the consequences. “Partial Control” is all we have on life, and therefore this category is very fascinating to me.

CWB: There is a slant towards abstractionism in your photos; do you consider yourself as an abstract artist?

RC: I think there is a lot to abstract photography and I still have a very long way to go in that aspect. I believe that human brain only works with and understands abstracts. If I tell you that a car is passing in the street, you will have no problem understanding me without knowing what color or model the car is, or how wide or tin the street is or any other details. Abstract photography is a way of talking about something without actually talking about anything. I think there is a great connection between abstract arts and cognitive science.

CWB: Do you like nature as much you enjoy experimenting with light elements? You do not have too many photographs in your Panorama section of your web site, but they are very interesting—even breathtaking.

RC: I like nature a lot, but I have to say I care more about experimenting with this art. Should my experiments lead me to nature, so much the better. The reason there are few photographs in my  panorama category is because it’s the newest one on my website! I just recently realized that to truly pay homage to nature, most of the time you have to break the limitations of your wide lens and do panoramas and tiles. I hope there will be many more pictures growing out of this idea to be in this category soon.

panorama category is because it’s the newest one on my website! I just recently realized that to truly pay homage to nature, most of the time you have to break the limitations of your wide lens and do panoramas and tiles. I hope there will be many more pictures growing out of this idea to be in this category soon.

CWB: Where do you go from here and what are your goals as a professional photographer?

RC: For the answer to this last question, I think I should talk a bit about my philosophy for photography, for this will explain where I will be going in this most amazing of arts.

A photograph is not a piece of art as much as it is a way of communication. In other forms of art, the communication concept is still there, but it is between the artist and the audience. For example, let’s say a painter is feeling something so incredible that he cannot describe with words, so what he does is he paints an incredible picture to describe it. In photography, however, the artist is out of the way, as well as “the way itself”. I mean the artist makes a tool of himself to be some kind of a bridge, a bridge to connect the subject and the audience together.

It is like telling a story: maybe you don’t like the ending, maybe you don’t like the story, but that does not matter. What matters is that the story has been told to the fullest from the point of view of the photographer. The story does not necessarily have to have a moral as much as the artist does not have to be idealistic. And so the next time I go out photographing, instead of trying to capture something fascinating and special, I will try to be humble and try to be listening with all my soul to hear if any scene calls for me to capture it, and then will be grateful for the opportunity.