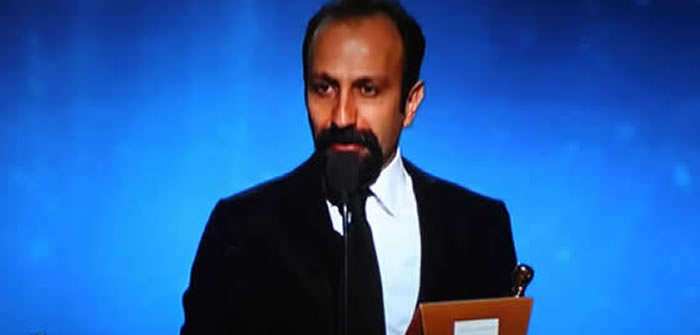

“Asghar Farhadi” is the title of a new book about the Iranian Oscar winning filmmaker by Tina Hassannia.

“Asghar Farhadi” is the title of a new book about the Iranian Oscar winning filmmaker by Tina Hassannia.

Tina Hassannia is a film critic and writer. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, The Globe and Mail, Slant Magazine, Reverse Shot, Maisonneuve, Guernica, Little White Lies, Keyframe, Grolsch Film Works, and others. She is the co-host of Hello Cinema, a podcast dedicated to Iranian cinema.

She was born in Tehran and lives in Toronto, Canada. You can find her online at tinahassannia.com.

Bijan Tehrani: What was that motivated you to write this book?

Tina Hassannia: I was approached to write about Iranian cinema by Tom Elrod at The Critical Press. Earlier this year he started this new publishing company dedicated to short books on film criticism. I had a few different topics in mind for this project, including the Iranian New Wave of the 1960s and 1970s or Jafar Panahi. I chose Asghar Farhadi because I felt like the world was ready for a full examination of his cinematic work — he’s received so much international attention, but it’s mostly been for his past 2 films, when in reality he’s made 6 feature length films in the past 10 years. This is not a creative output that should be overlooked by Western cinephiles, and I wanted to shed light on his previous films.

BT: What was your first impression after meeting or talking to Mr. Farhadi?

TH: I had already interviewed Mr. Farhadi once before, when he came to TIFF last year for The Past. But that was in a roundtable discussion and I only got to ask him a couple of questions. Even then, I could tell that he was the kind of artist who can turn even the stupidest question into a very worthwhile and interesting answer. We did a few long-form interviews over Skype for the book. At first I was intimidated by his intelligence but he’s quite generous with his time and his answers. He provides very comprehensive replies to every question, and as a film journalist I appreciate that level of mutual respect.

BT: was your experience interviewing Mr. Farhadi a challenging or an easy one?

TH: It was only slightly challenging because of the language barrier. I could understand about 50-70% of what he said in Persian, so I didn’t bother asking my interpreter to explain most of the things he would say (I waited for a full translation later). Similarly, he could understand most of what I said in English. But it was optimal for each of us to talk in the language in which we could best articulate ourselves – that’s Persian for him and English for me.

BT: What is that you like about Mr. Farhadi filmmaking and which one of his films you like most?

TH: I like that his films reveal how even the smallest decision in the world can have large, complicated implications on a person or a group of people, and how we make those kinds of decisions on a day to day basis. I like that his films explore the morality hidden in these decisions and how he films people’s reactions and body language as they respond to this kind of communication. I like that his characters are so well-fleshed out that he has virtually no “bad” characters. This is hard to do but it’s a very integral part of his filmmaking. I think A Separation is his best film, but About Elly and Beautiful City are also among my favourites. It’s hard to choose with him.

BT: How do you see the position of Mr. Farhadi among international filmmakers today?

TH: He’s cultivated a very high international profile and that means he can go into many different directions, including making more Western productions. That’s because The Past was a very successful co-production made outside of his homeland and he had the opportunity to work with some big stars, like Berenice Bejo. I’m hoping that he continues to work in Iran at some level, and that he can go back and forth between the different filmmaking stratospheres so that doesn’t limit himself to one kind of career. After talking to him, I get the sense that he wants the same multi-faceted kind of career.

A section of the book

A section of the book

A Separation is Asghar Farhadi’s magnum opus, a sui generis in his oeuvre, Iranian cinema, and indeed within the larger history of cinema itself. The production catapulted the filmmaker to a high degree of mainstream international acclaim and affected the political tensions between Iran and the West at a time of high tension. Its significance as a globalizing cultural product that updated the world’s blurry image of Iran should be neither underestimated nor forgotten.

“. . . A Separation is a fine account of Iran’s predicament; anyone interested in the mysteries of change and tradition—the difficulties faced by many people as they try and reconcile themselves to modern values and norms—will learn much from it,” wrote one anonymous writer for The New York Review of Books.(1)

The work continued Farhadi’s examination of the plurality of moral perspectives within a society entangled between modernity and tradition. But here, formally and narratively, Farhadi reached an aesthetic zenith. Here, more distinctly and clearly than in his other films, Farhadi demonstrates the problematic dynamics separating different classes, genders and generations. The film never favors one character over another—the religiously devout Razieh and her hot-tempered husband Hodjat are as relatable as the ostensible protagonist of the film, Nader. It’s fair to say that everyone in this film is prone to making mistakes—decisions they believe are right in the heat of the moment—and though the film begs us to judge them for it, we strangely find ourselves unable to do so.

Formally, Farhadi shows a colossal improvement between About Elly and A Separation. This is most apparent in narrative and visual style. Colors are muted and kept neutral on purpose (outside a few strands of bright red hair that dart out of Simin’s headscarf). The camera captures its characters and environments with a hyperrealistic eye, crisply making out the most mundane of details in spite of the constricted contours of apartments, corridors, staircases and vehicles. This is all thanks to Mahmoud Kalari’s stunning cinematography, which Farhadi had decided to collaborate on extensively in the months leading up to production. The two brainstormed ideas for the look and feel of the film, sharing notes on their favorite Iranian documentaries. (2) The handiwork has been (favorably) compared to Dogme 95, but combined with the kinetic, intuitive editing rhythm from Hayedeh Safiari, the end result is more dizzying and engrossing, planting viewers in the characters’ most intimate moments while obscuring their figures just behind the claustrophobic reach of doorframes, windows and other interior infrastructure.

The “button” for this film’s “suit” was an image of a middle-aged man washing his senile father in the bath and crying. Though Farhadi has never experienced this personally, his grandfather did suffer from Alzheimer’s.

“I wanted to know: ‘Who is this man? Where is his family? Why is he keeping his dad in the house? Why is he responsible for washing him? And does his father even recognize him?’ ” Farhadi told Roger Ebert. “And so many other questions. These really made different aspects of the story come to light for me.”(3)

1 Anonymous, “Tattered Lives in Divided Iran,” New York Review of Books, 2011, http://www.nybooks.com/blogs/nyrblog/2011/sep/22/tatteredlives- divided-iran/.

2 Mehrabi, Masoud, “Bitter Truth, Sweet Compromise, and Deprived Redemption,” Film Monthly, March 2011, Issue 424, 68-109.

3 Ebert, Roger, “Good People Facing Impossible Questions,” RogerEbert.com, 2011, http://www.rogerebert.com/interviews/good-people-facingimpossible- questions.