Hundreds of thousands of theater-goers will flock to Broadway this year to escape the reality of Donald Trump’s presidency and its never-ending onslaught of foibles, fabrications and faux pas. That is, after all, what live theater is for: a temporary respite from our neuroses, a chance to be suspended, in fiction, in real time.

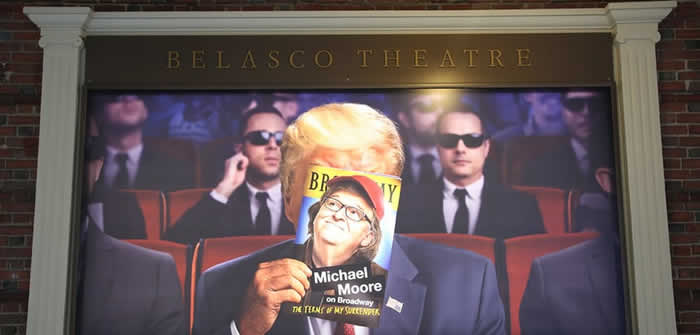

Michael Moore, though, is betting on just the opposite. With his new Trump-centric one-man show, The Terms of My Surrender, the documentarian and liberal firebrand is taking on the president seven days a week, using his powers of pomp and provocation to inspire in audiences the kind of righteous indignation he’s been expressing for decades. If the Great White Way seems a place ill-suited for the political humorist’s brand of populism, he’s hoping audiences view the show less as a lecture and more as a call to action.

But the show, directed by the stage veteran Michael Mayer, might be addressing the very people – thespians and Manhattanites – who already see the president as Moore does: dangerously incompetent, exceptionally narcissistic and pathologically untruthful. If Moore hopes to convert the unconverted, is a Broadway stage really the best place to do it?

For one, it’s an entirely new environment for Moore, who’s made his career writing, directing and producing politically oriented documentaries (Roger & Me, Bowling for Columbine, Fahrenheit 9/11) that challenge Washington’s conventional wisdom, from its veneration of the free market to the invasion of Iraq. Along the way he’s become hugely divisive, a patron saint to the left and political satan to the right; if one were to make a list of public figures best equipped to quell the animus that’s subsumed the country’s politics, Moore might come in last, right after the Dixie Chicks, Mel Gibson and Donald Trump himself.

But there remains something truly authentic about Moore; it goes beyond his drab uniform, baseball cap, duck waddle and self-deprecation. Moore certainly doesn’t need to take the stage every night and harangue audiences about Trump. He’s also aware the left needs some fresh blood, a new rabble-rousing spokesperson for progressive causes. And therein lies the most salient takeaway from The Terms of My Surrender: Moore badly wants to save the country from Trump, and he’s keen to hoist the flag, even if it’s time for a new flag-bearer.

So is the show anything more than a Ted Talk with set design? At times it’s exactly that, with Moore sharing anecdotes about his own activism, as if regaling a biographer; he’s told many of these stories before, as recently as the Women’s March in January. But at others it’s quite funny and creative, less a skewering of Trump and more a therapy session for those of us already exhausted, after just seven months, by his presidency.

Dressing the stage is a super-sized American flag. Before Moore appears from behind it, we see only his silhouette, a parody of Trump’s own WrestleMania entrance at the Republican national convention in Cleveland last year. When the stars and stripes split and Moore walks out to thunderous applause, his first words echo those of many Americans the morning of 9 November: “How the fuck did this happen?”

Moore, who hails from Flint, Michigan, is better acquainted with the answer than most. He spent the general election warning people of Trump’s impending victory, and his most recent documentary, Michael Moore in TrumpLand, found him traversing Wilmington, Ohio, among the Trump faithful before the election. In that sense, he fancies himself the ideal person to bridge the divide: an Academy Award-winning film-maker of humble midwestern origins, the 18-year-old who successfully ran for a seat on Langston, Michigan’s board of education and became a New York Times bestselling author 20 years later.

It was curious, then, to find Moore so often using the term we, as in: “We got more votes!” or “We’ve only got to flip 24 seats in the House.” The assumption that the audience at the Belasco theatre consisted only of Democrats – which might very well have been the case – ran contrary to Moore’s posturing as the populist prophet.

In the two-hour production, Moore shares several stories to illustrate how one person can make a difference: the librarian in Englewood, New Jersey, who protested HarperCollins after they refused to release Moore’s 2001 book, Stupid White Men, when it was deemed unfit for post-9/11 America; or Moore’s friend Gary, who went with him to Bitburg, Germany, to disrupt Ronald Reagan’s appearance at the burial grounds of former SS officers.

What makes the show worthwhile is less the content of these anecdotes than Moore’s own charm and comic deftness. A gag about the long list of banned items in a TSA brochure – including a cattle prod, leaf blower and hand grenade – circles back to Trump’s Muslim ban. A Canadian and an American are plucked from the audience to square off in a game of trivia. And when pre-planned “Moore 2020” chants begin, he stands at a podium and calls for universal charging devices and free joints for postal workers. Moore’s actual platform would include universal healthcare, not chargers, but the show is less concerned with policy than with passion.

Moore’s show is one of the first artistic products of the Trump era on a national scale. Until now, most parallels between pop culture and the political climate have been serendipitous at best; The Handmaid’s Tale was almost finished shooting by the time November rolled around, but in its depiction of a misogynist, theocratic hellscape became an emblem of resistance.

This raises the question of how to best to take on the president: directly, like Moore, Stephen Colbert, Samantha Bee and SNL; or indirectly, by exploring the tensions he’s inflamed in the body politic rather than the man himself?

It seems Moore hasn’t yet figured that out. The high point of the show is a diatribe about the Flint water crisis, a cause close to Moore’s heart, that offers an allegory for the perils of governance by racist businessmen. And even as Trump’s image appears on the show’s playbill, his orange hands and synthetic, barely hair visible behind Moore’s visage, overt references to the president seem designed for an easy laugh rather than striking an emotional chord.

By and large, The Terms of My Surrender is more about a) Michael Moore and b) Us than it is about the president. Yes, Trump looms large over the whole production, both as impetus and subject, but it’s neither a polemic against him nor a blueprint for the resistance. Instead, it’s a battle between two large men with large egos, one commanding the stage, the other our national conscience. As Moore confesses near the end of the show: “This country isn’t big enough for both Trump and me.” For the foreseeable future, it’ll have to be.

Source: The Gurdian